Reflections on a summer of design sprints

I look back on what we learned by running six design sprints over the spring and summer of 2021, both in terms of shaping the research and design technique to suit our circumstances, and in terms of what this has meant for shaping the future provision for prospective students.

Update: Presentation to Web Publishers Community

24 November: I talked through a slide deck which pretty much covers everything in this blog post at the University’s regular Web Publising Community meet up.

Background

Towards the end of 2020, it became clear to me that while there was an acknowledged need for a service and a website to replace the existing provision of degree programme information to prospective students, the whole planning process was at an impasse. Among a load of other strategic priorities, and the additional pressure of the pandemic, the replacement of the degree finders had stalled.

Our team’s resources were becoming increasingly tight, and it was easy to turn our attention to any number of issues that were coming up through the academic cycle rather than the big, long term one.

I wanted a means to build some consensus about what a future state might be, so that if and when the funding was secured for a major development project we had a halfway-decent idea of what we needed to do.

Most importantly I wanted this halfway decent-idea to be rooted in the evidenced priority needs of prospective students, and for the colleagues we serve in schools, colleges and central service units to have felt part of the decision making process.

Design sprints were the way I decided we might start to work towards achieving this.

What are design sprints?

I wanted a means for us to:

- Stay focused on the challenge of exploring the most important aspects of a potential future state

- Have a process to follow so everybody knew what they needed to do and when (so minimising the need for project management)

- Bring the prospective student into the process regularly in a human-centred process

- Engage colleagues in student recruitment and related specialist roles; both to participate in the research and design process, and to feel informed on what we were doing

Design sprints met all those requirements. I wrote about design sprints at the outset of this initiative, so if you don’t know what design sprints entail I recommend stopping reading this and coming back when you’ve familiarised yourself with my earlier blog.

Read my previous blog post introducing design sprints

What did we set out to do?

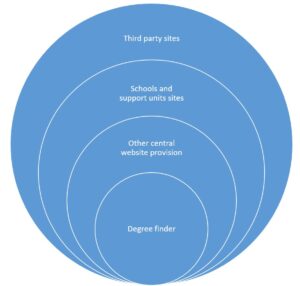

The degree finders sit in a much bigger ecosystem of websites that povide information for prospective students.

When you think about it, our degree finders aren’t really a “thing” in their own right. We have just put a label on the webpage outputs that pull together some information from various parts of the organisation that we think are useful to the student decision making process. This information happens to be in a particular content management system that we have identified as being past its ‘best before’ date and in need of replacing.

But these particular webpages don’t do everything the student needs. They sit amongst other web pages that the Prospective Web Content Team manage, and these sit amongst other web pages that other teams across the University manage, and these sit in a wider ecosystem of websites managed by all kinds of organisations that serve to influence prospective student decisions.

And all these web pages and websites exist among a range of other influencers and information sources; some digital, some not.

Reframe the problem

I prefer to think about what we are doing to influence prospective student behaviour in a more holistic fashion.

So rather than think: “What does a replacement degree finder need to do or look like?”

I prefer: “How do we empower enquirers and applicants to be more effective, efficient and satisfied with our prospective student information?”

My hypothesis was, and still is, that if we centre our online provision of information around what prospective students want to study, they will be more independently successful in establishing whether Edinburgh is a good option for them.

How do we empower enquirers and applicants to be more effective, efficient and satisfied with our prospective student information?

We already know broadly what is important to prospective students when they are deciding whether to apply. We also know what our student recruitment colleagues wish students would do. We see the same trends coming through in a range of insight sources: enquiry analysis, top task surveys, website analytics, usability tests, market research and so on.

We also know that too many tasks are too difficult for certain students in certain scenarios.

So rather than trying to design a new degree finder, we set out to explore new ways to provide digital services to prospective students in the areas that matter most to them and are most costly to the University when they don’t succeed.

Focus of our design sprints

My primary responsibility in all this was to set the direction; to prioritise the problems we wanted to explore and try and solve first.

Over the course of 6 design sprints we looked at:

- The search experience. What do students most value when identifying and comparing our programme offering?

- Personalisation. How might we keep content relevant at every stage of a prospective students decision-making process?

- Fees. How might we empower students to confidently calculate their total cost of study, understanding the elements that are certain, variable or estimated?

- Entry requirements. How might we empower applicants to understand their chances of application success regardless of the nature of the qualifications they hold or anticipate gaining?

- We looked at this from two perspectives: as a student holding overseas qualifications and as a UK student who would be eligible for a widening participation initiative

- Funding. How might we make all Edinburgh student funding opportunities findable and comprehensible?

Watch video summaries of what we built and learned in each sprint

There were more topics we wanted to explore, but with the time and resource available, this was the set I prioritised.

The order of the sprints was largely dictated by the availability of colleagues bringing the subject matter expertise, and our need to pilot and refine our design sprint process. Ideally the first two sprints would’ve come later. We also probably could’ve taken another approach to digging deeper into entry requirement instead of running a second design sprint, but for the logistical reasons I mentioned earlier we stuck to the one approach.

We may come back and undertake more design sprints further down the line, or we may decide to approach our other design challenges through other approaches.

Lessons learned #1

- Design sprints aren’t the best fit for all design challenges. For several good reasons we stuck with them through this period, but one or two of the things we covered could have been done effectively in other ways.

- Setting the initial problem statement is essential. Maybe not so much a lesson learned as the Sprint Book and many others emphasise the importance of this. Nicola and I invested time in this before sprints and it certainly paid off for us.

- We can burn out if our pace is too fast, just like agile development. I listened to the team and tempered my ambitions in terms of the number of sprints we would cover in the time we had.

How did we do it?

If you read my earlier blog post, you’ll know that the original Google Ventures Design Sprint was envisaged to take place with a consistent team working together for five days.

Since the book was written in 2016, the technique has been reshaped in a number of ways to meet the needs of different organisations and situations.

The key considerations as we designed our design sprints were:

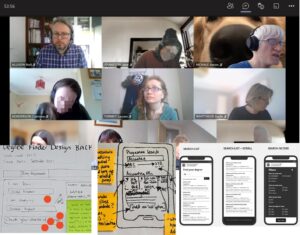

- We were in the middle of a pandemic so our sprints had to be online, with everyone contributing remotely

- We needed to involve subject matter experts who practically were the owners and deliverers of particular student-facing services, because while we own the degree finder we’re not experts in, say, tuition fees. Our colleagues couldn’t commit to a week.

- We were looking at key things that a student needs to make their decision on whether to apply to study with us. But how and when students used these things could vary considerably. There isn’t really a single path or story of how a student comes to apply. And because of this complexity, no one really has a comprehensive handle on what happens.

So with all this in mind, we decided we would:

- Gather as much insight as possible before the sprint and play that back in the first workshop, rather than rely on a small number of ‘expert interviews’. Once our UX Lead had summarised what she’d learned in the preceding week through interviews, analytics etc, our subject matter experts had a chance to layer their own experiences on top.

- Run two half day workshops involving our team and our subject matter experts, and then leave the remaining work to refine a prototype and test it to our team alone. (Our subject matter experts were often incredibly helpful in finding student participants for tests though)

- Play back videos of students interacting with our prototype concept not just to our team and the subject matter experts who had participated in the workshop, but to anyone in the University who wanted to join us. There have been lots of downsides to the pandemic, but one definite upside has been the number of people who were able to join us for these playback. We had far more attendees than if we’d done this in person.

Lessons learned #2

- Research before the formal sprint window. In our first sprint, we tried to interview subject matter experts but found the experience didn’t really add the kind of insight we needed to go into problem definition, prioritisation and sketching.

- Extending the time around each sprint helped us better prepare for workshops, and also set a pace which (while still pretty nippy) cut back the feeling of being burned out. Broadly speaking we followed this cycle:

- Week 1: User research, analytics, desk research

- Week 2: Collaborative workshops, prototyping and testing

- Week 3: Team and open invite playbacks. The team watched everything, but we limited the public shows to just the most interesting 3 or 4 participants. We didn’t want to waste people’s time with repetition, and by guaranteeing a playback session no longer than 90 minutes most people stayed til the end.

- The workshop design evolved throughout the 6 sprints. We always had a team retro, and our Sprint Lead Nicola and I discussed, tweaked and evolved activities. The balance of time for discussion and prioritisation, and time for iterative sketching was the main challenge we faced across our two 3-hour sessions each sprint.

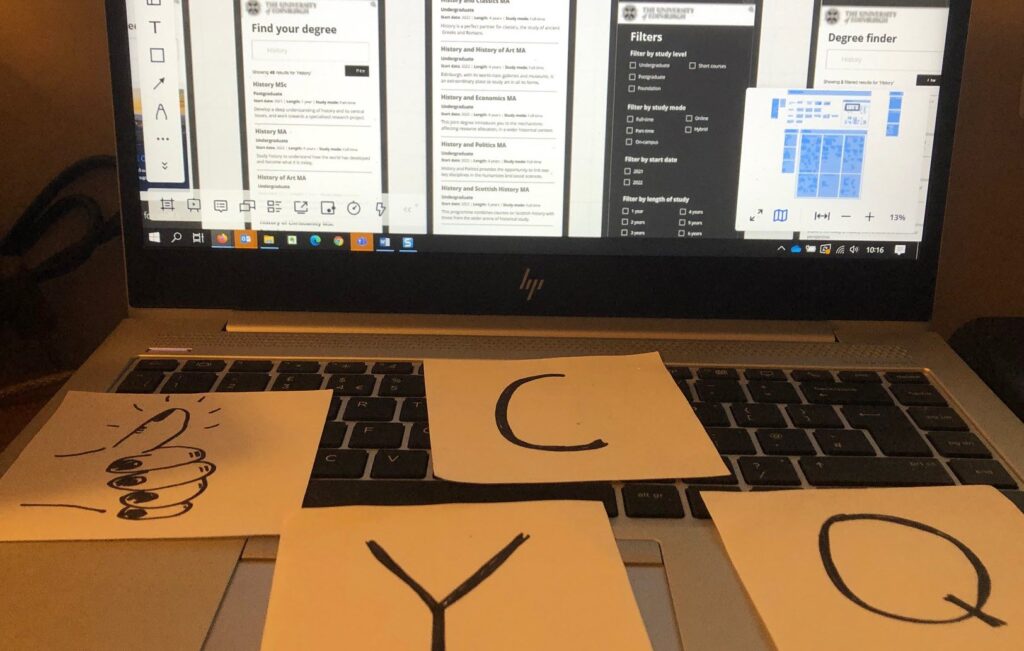

- Encouraging non-designers to sketch and share when we weren’t in the same room together was hard. I’d never encountered this as a problem in the past when we’d done in person collaborative sketching. But Nicola brought in some great warm up exercises to build everyone’s confidence, and while this ate into our limited time it was totally worthwhile.

- Using response cards helped engagement of online participants. We had a ‘Question’, ‘Yes’, ‘Comment’ and ‘Thumbs Up’ card each which worked so much better than the simple ‘Raise hand’ feature in Microsoft Teams. Nicola didn’t need to monitor the chat so closely while facilitating, and everyone contributed at key points without necessarily needing to speak.

The cards we used enabled sprint collaborators to contribute efficiently in a more nuanced way. Cards signified: “Yes”, “Comment”, “Question” and “Thumbs up”

What did we achieve?

First and foremost, we discussed, explored, refined and focused a series of design challenges we need to overcome if we are to produce a replacement for the current degree finders that meet prospective student and business needs.

We have six prototyped concepts that on the whole worked pretty well, albeit with:

- areas needing refinement and improvement

- audiences still to try them out on

- alternative approaches to explore (just so we’re clearer whether the approach we took was the best available)

- important areas of content and functionality still to explore

Just as important as knowing what works, we know about things that don’t work for the intended audience.

Design sprint workshops brought together subject matter experts from across the University to co-create potential solutions to big student problems. Then we quickly got feedback from current and prospective students.

Learn fast, learn cheap, and in the open

We did all this learning quickly, cheaply and collaboratively:

- 6 sprints were done in 20 weeks between mid-March and the end of July

- 27 subject matter experts contributed directly in the sprint workshops, each giving up two half days to explore, prioritise and co-design with us

- 43 students undertook user research interviews and tested our prototypes

- 176 colleagues booked to watch playback sessions of students interacting with our prototypes

I’m particularly proud of these numbers as pressure on staff across the University through this period has been intense, with everyone doing more work with fewer resources. For example, our team managed to deliver these sprints despite losing two content designers over the period which reduced us to about 40% capacity and all the while we maintained our usual operational services.

Our commitment to co-design with our service partners was met. Indeed, had we been able to run in person workshops, these numbers would have been significantly higher. I’m only disappointed that we weren’t able to involve students in the co-design process.

And we managed to prioritise working in the open and sharing our learning with colleagues from across the University. You can see all the invites to come to our playbacks in blogs we posted through this period.

Lessons learned #3

- Prioritise subject matter experts over team members for workshop attendance. We always knew that 8 to 10 people was the maximum we could cope with in an online workshop session without resorting to breakout rooms. In early sprints, we made sure everyone in the team was actively involved, which meant that there was only room for 3 subject matter experts. But by the time we got to the later sprints we had 6 or7 actively taking part, while the team largely observed and asked questions.

- Open playback sessions can be led by any of the team. At first, our UX Lead, Gayle, led the playback sessions the week after the sprint and research completed, but this put extra pressure on her as she also needed to focus on research for the upcoming sprint. Meanwhile, other members of the team could relax (well, not really) until they were needed in the next round of workshops and prototyping. Our playbacks follow a well established format, and we agreed that content designers would take over responsibility for running these sessions, leaving Gayle with more time to work with Nicola on what was coming up next.

- Three weeks is a realistic(ish) cycle. We originally envisaged working to a two week cycle but after two sprints (and even with a break over Easter) we realised this was too much. At the end of the six sprints, even when allowing three weeks, we had a backlog of tasks that were outstanding. We hadn’t written up our research findings. We hadn’t consolidated our prototype. We hadn’t shared the prototyping load – Nicola remained our single expert using the prototyping software Axure.

- Time to reflect is vital. We halted our sprints at the end of July while everyone took a well-deserved break. On return we acknowledged that we needed time to reflect and consolidate before going further – not least because sadly Gayle was leaving us for a new role in the Scottish Government.

What comes next?

Which brings us to what has happened since and what will happen next.

We needed to halt our sprints, even though there are two or three other priority areas it would’ve been great to explore. The main reasons for this were:

- Gayle was leaving, so we needed to prioritise time for her to work with Nicola and properly document work that had been done so far (and a few other things that had fallen by the wayside slightly).

- It was the start of term, which is an incredibly busy time for everyone and so our subject matter experts wouldn’t be available for user research or workshop participation.

- We needed breathing space to summarise, communicate and plan.

- Our content refresh cycle began again meaning that content designers weren’t as available for workshops, prototyping and user research.

And now here we are in November, which feels a long time since the last sprint ended.

But – in no small part down to Nicola’s continued efforts – we have:

- Brought together all our learning to outline and prioritise what we need to learn next.

- Written up showcases of the prototypes we developed, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses. We’ll share these soon, and link from this blog post.

- Shared our student journey mapping work which informed all our sprints in increasing levels of detail as we conducted each round of research. This was presented to marketing forum and is available for staff. Read my post about the prospective student experience mapping playback session

- Engaged the services of Manifesto, who are the design and development agency currently working with Website and Communications to deliver the University’s new Web Publishing Platform (in other words, the replacement for the current EdWeb Content Management System). As we know that our future service needs to be as aligned to this new platform as possible, this was an obvious choice. We are just about to begin a mini-project to set out a costed plan for the full design and delivery of our degree finder replacement.

We have much still to do in terms of understanding and validating prospective student and business needs, and I can see us returning to design sprints as a way to kick start our understanding in key areas.

I’m also excited to see progress with colleagues over in Website and Communications who are developing the new Web Publishing Platform to replace the EdWeb Content Management System. Our own development work will be done on the back of what they achieve, and with Manifesto helping us to map out how this will happen, 2022 promises to be a very interesting and busy year.

3 replies to “Reflections on a summer of design sprints”