Lessons learned from usability testing under time pressure

This blog is part of a series on a mini-project the Content Operations team completed in August and September 2024. In this instalment, I review my approach to usability testing for new postgraduate funding content, highlighting what I would do differently if I could do it over again with a little less time pressure.

For more information on the other stages of this project, see our individual blogs:

- Improving student understanding of postgraduate funding and UK government loans: a Content Operations mini-project

- Defining the scope: Background, research and user needs

- Right information, right place: Channel mapping and content drafting

Time pressure challenge accepted

We started this project in the summer with a deadline of 1 October 2024 – the go-live date for the new edition of the 2025 entry edition of the postgraduate degree finder – so that publishing the new content would coincide with publishing the new degree finder edition.

We had finished drafting the new content and had received some initial stakeholder feedback on it by mid-September. At this point had less than three weeks to go until our planned publication date, and needed to consider testing the content’s usability in advance of publishing it.

Jen and I were faced with a challenging question: How do we approach testing the usability of the new content with such a tight deadline? We set out to tackle the challenge as effectively as we could, knowing that taking some shortcuts in testing is better than not testing at all!

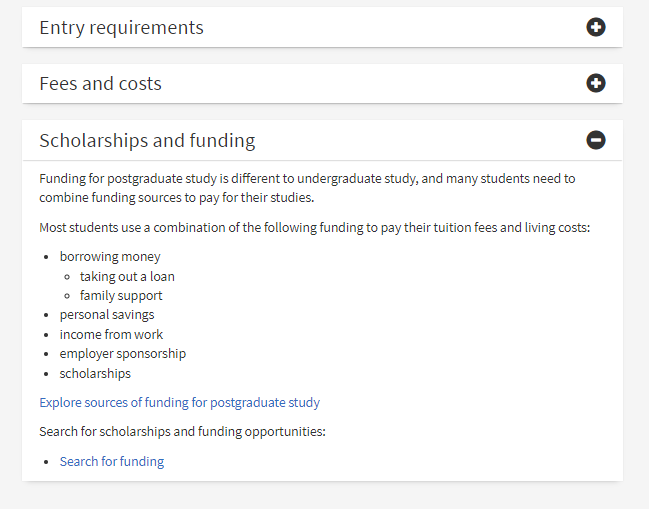

PG degree finder ‘Scholarships and funding’ content

We first arranged to test the content which had been added to the ‘Scholarships and funding’ section on a postgraduate degree finder programme page.

Postgraduate degree finder programme page with new content in ‘Scholarships and funding’ section

For this test, we recruited two participants who are members of the wider Prospective Student Web team (PSW), but had not been involved in this project up to this point. One participant is also a current undergraduate student; the other is a university graduate. Both participants showed good understanding of the information, and their expectations of what they would find at the destination link were consistent with our aims.

Additional feedback

We then shared it with PG degree finder editors. Overall, we had very few requests to change or amend the content. However, there were a couple of significant instances (with STEM doctoral programmes) where our content wouldn’t work without a bit of re-jigging.

The first was postgraduate research programmes in Maths, as full scholarships (fees and a stipend to cover living costs) are widely available. We decided to rework the content for these programmes to make it clear that the vast majority of students are fully funded (and arguably, this is a great thing to highlight specifically!)

The remaining programmes that were unique fell into the unusual category of basically being fully funded by an external agency – a successful applicant to one of these programmes will have their tuition fees fully funded and will receive a stipend for living costs. As such, we decided to just leave out our blurb for these programmes, as that might confuse things for applicants.

In the end, we changed the content for these outlier programmes and have kept a list of these for future reference. We suspect we’ll come across a few more of these in future years, but it was a good way to test the content against real examples, and to see how we can vary it while still staying true to the spirit of the exercise.

| Tips for next time: |

Our approach to testing this new degree finder programme page content worked well overall. If we’d had more time, we would have:

|

PG Study site content

We tested content that had been drafted on the following PG Study site pages:

- Funding your studies (Overview page)

-

- Loans (Child page)

-

-

- UK government loans for postgraduate study (Child page of Loans)

-

- Scholarships (Child page)

- Other sources of funding (Child page)

Planning an approach to testing

To start planning how to test the content on these pages, Jen and I sat down and made some rough notes on:

- which parts of the new content we wanted to test as a priority

- how we could phrase questions for participants that would prompt them to engage with and test the content

We wanted to prioritise testing the new content, how the user interacted with it and journeyed from one page to another, and how they interacted with the content on individual pages.

We drafted phrasing of questions for participants that related to this content, including:

- Could you tell me what options you have for funding your studies?

- Are you eligible for a UK government postgraduate loan?

- How much of your total costs do you expect will be covered by a loan?

This initial focus on the content to be tested and the questions we wanted to ask shaped how we planned the structure of each test that was carried out.

| Tips for next time: |

| When approaching the first steps in planning usability testing, start with defining the goals of the testing activity. Your defined goal keeps you focused with something to refer back to as you proceed with planning the structure of your tests.

The goal of usability testing for this content could be defined as: To find out of if changes made to content make it easier for a prospective student to identify their options for funding PG study In this step-by-step guide, Maze highlights that the first step in the usability testing process is to define a goal and target audience: |

Testing a sample of scenarios

In order to test the ‘UK government loans’ content with a participant, we would need to present them with a scenario, and then ask them if they would be eligible for a UK government postgraduate loan in the context of this scenario.

A prospective student’s eligibility for a UK government postgraduate loan varies on a variety of factors, including (among others):

- where in the UK they normally live

- their chosen mode of study (for example, full-time or part-time)

- their chosen programme’s outcome qualification (such as MSc, PhD, and so on)

I realised that if we wanted to test the usability of the eligibility content for all of the variable factors across potential users, we would need to test at least 15 different scenarios with participants. Our tight timeline meant that we would not be able to recruit enough participants and conduct this number of individual tests before the publishing deadline. I suggested that we instead carry out four usability tests, so that we could cover a sample of the many possible scenarios.

I chose the following four scenarios for testing because I (anecdotally) assumed that these would be the top four scenarios that apply to most of our prospective postgraduate users:

- English domiciled; interested in a doctoral programme; seeking full-time study

- Scottish domiciled; interested in a taught masters programme; seeking part-time study while working full-time

- Welsh domiciled; masters graduate; interested in a taught masters programme; seeking full-time study

- Northern-Irish domiciled; interested in a taught masters programme; seeking full-time study

| Tips for next time: |

| In rushing to choose which scenarios to test based on my own assumptions about our users, I missed a key opportunity to base my choice of test scenarios on real evidence of user needs.

For future testing activities, this evidence can be gained from:

and/or,

|

Session guide

In preparing a session guide, I first wrote up a general script that could be varied slightly for each scenario to be tested.

I then added a section in the guide for each of the four tests, where each section included:

- the relevant variation of the introductory script

- a table that listed:

- each of the scenario tasks

- the outcome pass criteria for each task

- a column for noting the pass or fail status of the task

- space for making general notes on the test

Finally, I added two further sections to the guide for a summary of test results and recommendations for further content edits.

Including all of this in the session guide meant that all of my notes on planning and testing were in the same place, but it made for a very lengthy guide. I realised that my guide was far too long when I found myself thinking about adding a table of contents!

| Tips for next time: |

| Keeping the session guide concise and relevant to the activity is important; other facilitators should be able to read your session guide in a few minutes and from reading it, should easily understand how they can facilitate a test with a participant.

Stakeholders who are interested in a summary of your test results and recommendations from the testing activity will be overwhelmed by a detailed session guide. Writing up your summary and recommendations in a separate document that you can share with stakeholders will make this information accessible for readers who have not previously been involved in the testing activity. |

Recruiting participants

For the website content tests, we recruited four participants who are members of the wider Prospective Student Web team, three of whom had not been involved in this project up to this point. Two participants are also current students; one undergrad and the other postgrad. The other two participants are university graduates.

Recruiting participants from within our team created lots of opportunity for bias; participants had varied levels of familiarity with the aims of the project. For some of these participants, the test tasks were too relevant to their personal circumstances, meaning that bias was introduced when they brought their own assumptions and experiences when approaching a task.

| Tips for next time: |

| For representative results of usability tests, it’s important to test representative tasks on representative users. If your participant’s personal circumstances mean that they are too familiar or unfamiliar with the content you are testing, you are unlikely to see results of your tests that reflect the personal circumstances of the user who will ultimately engage with the content.

A more effective approach to recruiting for these tests would involve:

|

Participants’ responses to the test scenarios

In order to provide context for the tasks that would follow, each participant was given a specific scenario at the outset of the usability test. The participant was asked to apply this scenario to how they approached each of the tasks involved in the test.

The details of each specific scenario were provided so that we could test participants’ understandings of the new content on one page in particular: ‘UK government loans for postgraduate study’.

Here is how one of the scenarios was described to a participant:

You are an English domiciled BSc graduate applying to study a postgraduate doctoral programme full-time.

You want to know how you can fund your studies. You have come to this webpage to find the information.

In each case, the participant then attempted to the tasks that followed in the context of their given scenario. However it was clear that all four participants found this challenging; we observed each of the following behaviours in more than one participant:

- asked the facilitator to repeat or clarify details of the scenario for their understanding before the first task was presented

- asked for the scenario wording to be repeated when they were in the middle of completing a task

It became obvious that the scenario presented to each participant was too complex; participants found it difficult to remember the details throughout the test and experienced additional cognitive load, meaning that the test activities did not flow naturally.

In one case, specific details of the scenario were too unfamiliar for a participant, meaning that they misunderstood the scenario and were unsuccessful in a task as a result.

| Tips for next time: |

| Recruiting participants who are representative users for the test’s scenario(s) may reduce the effect of cognitive load on how a participant engages with test activities. However in this case, it’s worth considering how the test design could be adapted to make the instructions more straightforward for a participant.

For example, if approaching the test design again, we could change the current design and instead:

or,

|

Reviewing recordings of tests

Few of us enjoy watching or listening to recordings of ourselves. I was the hardest part of this usability testing experience for me, but I forced myself (with a fancy takeaway coffee as my reward!) to rewatch the recordings of the tests I facilitated for this content.

In my rewatch, I noticed some of my own behaviours that I could develop or improve upon so that I would be more effective or unbiased in my facilitator role in future tests. For example, I noted that I forgot to ask one participant a question from my testing guide because I let the participant develop on their previous answer in a lot of detail.

I also noticed myself asking participants leading questions at times, encouraging them to find the relevant information and succeed at the task. This introduced another element of bias to this testing activity, but can be mitigated in future testing if I focus on improving on my facilitator skills.

| Tips for next time: |

| Rewatching recordings of usability tests you facilitated may cause you serious cringe, but it’s the best way to highlight areas for improvement in your skills as a test facilitor, ultimately reducing your own contributions of bias and achieving more reliable and insightful test results. |

The value of (hurriedly) testing this content before publishing

While our usability testing design approach had its limitations, we still gained very useful learnings from the tests that we carried out. Participant responses to tasks showed us some places in the content where we could make small changes to make it easier to understand; some examples of the changes we made in response to test results include:

- updating a sentence’s punctuation when we noticed it had caused a participant to misinterpret its meaning

- adding a sub-heading before a paragraph when we noticed that several participants had not identified it while scanning a page for relevant information

With these changes made, we shared the draft content once more with stakeholders in advance of publishing to request any additional feedback they could share. The round of usability testing we had completed for the content – although slightly rushed! – provided some useful evidence and insights about what worked well and what could be improved in the content we had developed.

Special thanks to our team’s UX Specialist Pete Watson for his input on the ‘Tips for next time’ content included in this blog.

Next up – Overview and next steps

Read more about the postgraduate loans mini-project and our next steps