Mapping the prospective postgraduate research applicant user journey

The process of user research with prospective PhD students challenged our early assumptions of the applicant journey. We evolved our initial thinking, leading to two new and distinct user journey maps.

In 2023, we undertook user research to inform the design of a research degree profile and supporting website content. We’ve already played back our findings to the University’s marketing and student recruitment community, but we wanted to create journey maps to present what we know at a glance. The event write up contains a link to the slides and video for University of Edinburgh staff.

You might also like to read the blog post about why we created user journey maps and how best to use them.

Why it’s useful to have user journey maps and how best to use them

Our initial user journey map – internal assumptions

I’ll start with the initial maps we created based on our assumptions and internal perspective to show the complete mapping journey. Then, I’ll share updated user journey maps based on our research insights to understand what prospective PhD students do to find and apply for a PhD.

The initial internal view was that there are 2 separate user journeys depending on the subject area and that the user journey differed according to whether the applicant was applying for a:

- Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) PhD

- Humanities PhD

To summarise, we thought that applicants for STEM PhDs would look for a project, and the applicants for Humanities PhDs would search for a supervisor.

The initial user journey map for a STEM PhD candidate

Our starting point for mapping the prospective PhD students was based on interviews with staff. Consensus internally was that there was a distinct user journey for science and technology students. Interviews with actual students showed this was not the case.

The internal view of the steps taken to apply for a STEM PhD

While working in a lab, the applicant encounters professors with a PhD and people doing a masters by research (MScR) and PhD, so they know that the next natural step in their line of work is to do a PhD. They know the route to follow to get onto a PhD programme.

Applicants look online for advertised projects and find PhD studentships or doctoral programmes.

PhD studentships

PhD studentships mean working with a Principal Investigator on projects advertised on external sites (for example, findaPhD.com). These have a scholarship attached, so there is no funding application step for the applicant to complete.

After finding a list of suitable studentships, the applicant refines them based on location, content, institution and potential supervision and then applies for the project.

Doctoral Training Centres and Partnerships

Doctoral Training Centres/Centres for Doctoral Training (DTC/CDT) and Doctoral Training Partnerships (DTP) are consortia formed by several collaborating partners, including industry, academia and funding councils that offer funded PhD places.

They offer a more structured approach to gaining a PhD. They are cohort-based, take 4 years, and include training and a supervision team. In contrast, with the traditional 3-year PhD format, a PhD student has one supervisor, who may have multiple PhD students. They typically don’t include training. Many more CDTs and DTPs exist for STEM subjects than for the humanities.

There was an expectation that Doctoral Training Centre candidates might not be in a lab setting when they began looking for a PhD and might not be aware of the process to follow to find one. As a result, stakeholders thought they might search for these types of PhD similarly to finding a masters degree.

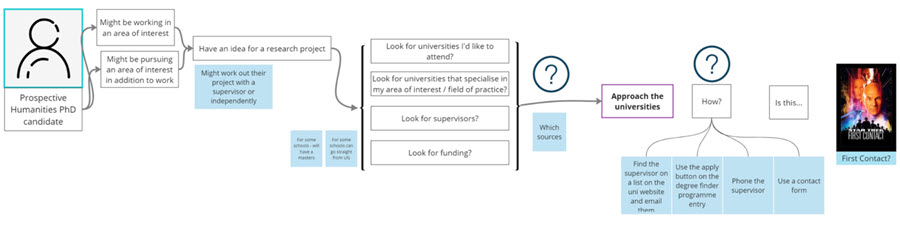

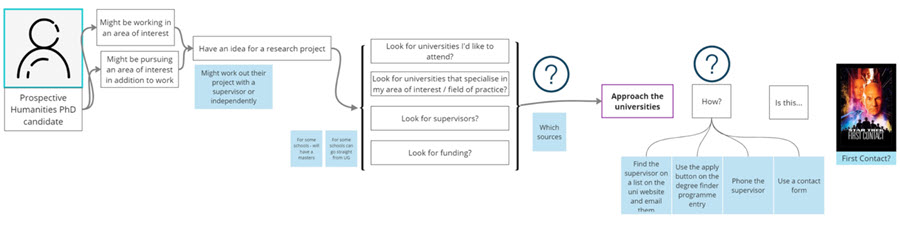

The initial user journey map for a Humanities PhD candidate

Our starting point for mapping the prospective PhD students was based on interviews with staff. Consensus internally was that there was a distinct user journey for humanities students. Interviews with actual students showed this was not the case.

The internal view of the steps taken to apply for a Humanities PhD

Prospective Humanities PhD candidates could be working in an area of interest, pursuing an area of interest in addition to work, or have an idea for a research project.

They research possible opportunities by looking for:

- Universities they’d like to attend

- Universities that specialise in their area of interest/field of practice

- Academic supervisors

- Funding

Staff didn’t expect prospective PhD candidates to follow these steps in a strict sequence; instead, they expected a more organic and iterative route.

Internal view of the knowledge applicants would have of the process to follow

There were also internal assumptions about how much people would know about finding and applying for a PhD.

Staff expected that individuals beginning their application in the following circumstances would not know how to apply:

- Recent undergraduates

- People working in a non-academic setting

- People who contacted an individual academic outside of an academic setting

- Someone who applied ‘cold’ via Degree Finder, that is, without speaking to any university staff first

They assumed that specific STEM candidates would have complete process knowledge and that recent PGT or MScR graduates would have some process knowledge.

An updated perspective on the journey based on user research

Insights from user research on our assumptions

Participants’ knowledge of the process was often not as we assumed

Knowledge of the process was low across all participants, including those applying to STEM PhDs, and knowledge of the process did not correlate with any journey starting points.

STEM candidates working in a lab mostly knew they needed to find and complete a project, and when asked if they knew how to go about it, they answered ‘yes’. However, the process they set out to follow was based on their assumptions, which did not always match the University’s process.

For example, a research participant doing a lab-based STEM PhD followed the anticipated process that it was assumed a Humanities applicant would follow. He looked up academics and made direct contact because that is the standard process in his home country. He knew that the process followed in his home country might be different overseas, but he followed the process he knew rather than checking it out.

Not all STEM participants saw doing a PhD as their natural career progression. One such participant had never considered a PhD as an option, and only did so at the suggestion of a lecturer on their undergraduate degree programme.

Humanities PhD applicants often worked in an area of interest or a related field, and their knowledge of the process varied. Even when they understood it well, specifics could still catch them out.

Processes were not always as we assumed

There was a general sense that the PhD application process would be the same across UK universities. However, that did not appear to be the case. For example, a participant who had applied to the University of Edinburgh and the University of Cambridge for a Humanities PhD said their processes were the opposite. They had to find a supervisor for the University of Edinburgh before applying; for the University of Cambridge, they applied and were assigned a supervisor.

Some of the advertised PhD projects state that the applicant should email the lead academic for an informal conversation in the first instance. Again, this was assumed not to be the case for STEM candidates.

Participants applying for a Doctoral Training Centre or Partnership did not always behave as assumed

Some Doctoral Training Centre programmes appear in initial PhD search results, and candidates review them like an advert for a scoped and funded PhD project.

There was a mix of understanding regarding what a Doctoral Training Centre or Partnership is, even among participants involved in one.

Applicants to Doctoral Training Centres or Partnerships were no more or less likely to know the process than applicants to other types of PhD.

The application process differs depending on the type of PhD rather than the subject area

How you apply for a PhD programme differs depending on:

- Whether an applicant applies to a pre-scoped project or proposes their topic for a PhD research project

- Whether funding is already secured for the scoped project or proposed research topic

- Whether academic supervision is already in place for the PhD student

Applying for a pre-scoped, funded project

A researcher or a research group or centre scopes a research project, secures funding, and advertises it as a studentship. Successful applicants complete the scoped work, which earns them a PhD.

The application process for this type of PhD is stipulated in the advertisement and may vary depending on the institution and the nature of the work. However, it does not require the applicant to propose an area for original research or find funding.

Applying to propose your own PhD research topic

In this type of PhD, the applicant must identify an area in which to conduct original research. Opportunities for this type of PhD programme are not usually funded; the onus is on the applicant to secure funding themselves.

This is also called a ‘self-directed’ PhD or self-directed research.

Academic supervision

A PhD student will conduct their research under an academic supervisor. This is the case for both types of PhD.

For a project-based PhD, the supervisor is typically the lead academic or Principal Investigator (PI). However, for those proposing their own research topic, there will be an additional step to identify an academic who can supervise them; this process can vary depending on the institution and the nature of the opportunity.

Areas for confusion

The above processes appear straightforward when stated explicitly. However, there is potential for a lot of confusion if you are unaware of the main distinction between the 2 types of PhD.

There are variations within the main distinctions

During the research, we observed variations in all areas.

- Scoped projects which did not have funding secured and which were advertised alongside other projects and opportunities

- Applicants applying for self-directed STEM research because they couldn’t find an appropriate PhD project advertised for their research topic. They collaborated with an academic to scope a project and apply for funding.

- Humanities research opportunities with funding secured

- Studentships which asked applicants to contact the academic supervisor in the first instance

- Self-directed PhDs

- which did not require the applicant to establish academic supervision before applying for the programme

- which did require the applicant to establish academic supervision before applying for the programme

There are variations in the processes within the University of Edinburgh

Graduate Schools set the process that is appropriate for them. For example, to apply for self-directed research, some schools require applicants to identify potential supervisors from the staff list and contact them by email. Others require the applicant to email the postgraduate administration team so they can assess the research topic and either make a match with a supervisor or provide a short list of staff for the applicant to contact.

This could be confusing if participants encountered differences between the core website guidance and content on a programme page or school website.

Different types of PhD opportunities are presented alongside each other in the main online tools advertising PhDs

Institutions advertise all opportunities:

- Scoped and funded projects

- Scoped projects without funding

- Opportunities for supervision of self-directed research in particular subject areas, with and without funding attached

When applicants encounter this as their first step, it is challenging to tell that there are general processes to follow, and it can seem like there are none.

The process is not always explained clearly or at all

We reviewed several University websites during the research and found that explicitly stating the PhD application process wasn’t common. Our explanation and guidance on the central University of Edinburgh Study website was unclear and incomplete.

There was a gap in our online provision on when and how to contact an academic supervisor

We did not adequately explain when and how to contact an academic supervisor, which caused confusion and anxiety for prospective students. We encountered examples of people following the wrong process by mistake:

- Contacting the lead academic for a scoped project when it wasn’t necessary, based on peers’ experiences of applying elsewhere and lacking clear guidance on the University website.

- Submitting a PhD application using the ‘Apply’ button on the Programme Page without speaking to anyone at the University. This can be the correct process for other institutions. However, it showed they had not found or understood the online instructions to make contact before applying.

- Confusion about how to find an academic supervisor

- Participants wanted to know what to include in their enquiry email to an academic, for example, a simple outline of their research question or a fully worked-up research proposal.

- There was concern that contacting an academic to enquire about supervision could negatively affect their PhD application.

- Once participants enquired about supervision, they wanted to know how long to allow for a response and whether to contact more than one potential supervisor at a time.

We didn’t make it clear where to find pre-scoped projects

At the time of the research, the University website directed visitors to the degree finder programme page. Consequently, participants misunderstood this page as a project advertisement and became confused.

Projects are published on the School, Centre and Institute pages, not the central site

However, these were not linked clearly from the programme page. Some people managed to overcome this, but not everyone. Some contacted a supervisor when they did not need to.

Comparing PhD programmes is not as easy as comparing taught programmes

Unlike the standard structure for undergraduate and taught postgraduate degree programmes, PhDs don’t have a set of standard content to compare. Plus, universities take different approaches to where they advertise available research projects on their websites.

This reflects the nature of this level and type of study, but it adds complexity to the journey for those who don’t know how to find and apply.

Aggregator sites like FindaPhD.com and phdportal.com list funded and unfunded projects alongside funded and unfunded opportunities; this can be confusing for those who don’t know the process. For example, it isn’t apparent what it means for something to be labelled ‘Self-funded’, ‘Funded PhD project’, ‘Competition Funded PhD Project’ or ‘PhD Research Programme’.

Knowing the process gives PhD applicants a distinct advantage

This starting assumption was borne out and built on in the user research.

When participants in our research did not know how to apply, they got very confused when searching for a PhD and navigating information online.

When participants knew what to do, they could approach the task in a more structured and systematic way. If they knew they required funding to study, they looked for funding. If they knew they had a decent research proposal, they set out to find the right programme and supervisor and then looked for funding.

Most participants who knew the process knew it because they had been through it multiple times, learning it organically. Some participants knew the process because their relatives or peers had been through it.

The prospective PhD student user journey maps

The user journeys mapped show the process for applicants who do not know how to find and apply.

There are 2 different user journeys depending on the type of PhD people are applying for:

- Project-based: applying for a pre-scoped and funded PhD research project

- Self-directed: proposing your own topic to research

For both of these journeys, the starting point is the same.

For most participants in our research, the main part of the application process took place outside of official systems. For traditional format PhDs, the candidate selection process took place in discussion with departments and potential academic supervisors before the final application form was submitted via the University systems.

For CDTs / DTPs, the processes differed – some were similar to the traditional format, and others asked for submitted applications through a dedicated portal first.

Motivations, starting point and journey duration

The main reason research participants gave for doing a PhD was to contribute unique knowledge to the field. In their actions to find a PhD programme, it was clear that there were 2 major priorities: career progression and studying the subject of interest.

For some participants, studying the subject for interest was the top priority, for example, those who had retired. For those still in employment, career progression is featured in combination with a deep interest in the subject. For those pursuing a particular type of science career, their PhD was more linked to progression in the field.

The duration of the user journey varied widely

Some participants had a short journey because they decided to pursue a PhD and had a straightforward experience of applying and being accepted onto a programme.

Others faced a much longer journey, lasting several years, as they needed time to find the right supervisor or programme.

Several participants paused the application journey to build the necessary experience and knowledge to be eligible for a PhD programme, which can take several years.

The starting points also varied widely

Individuals could begin a PhD from multiple starting points:

- Directly after completing an undergraduate degree, finishing a taught postgraduate degree, or a master’s by research

- After working in their profession for many years

Some participants planned to do a PhD from the start of their post-secondary education. In contrast, others only considered it after finding a suitable opportunity by chance or one being recommended by an academic or peer.

People learned the process of finding and applying for a PhD organically

Many people conducted extensive research into available PhDs to understand how the process worked, rather than starting by finding out what the process entailed and then going through it.

They didn’t need to know the overall process; they only required knowledge of their specific journey. Once they identified the route applicable to them, they looked no further.

Consequently, encountering information related to processes for both types of PhD in the later journey steps could be quite confusing, as they might not immediately recognise it as relevant to the application process for a different type of PhD.

The updated user journey maps

Following the user research to inform the design of a research degree profile and supporting website content we’ve now updated the user journey maps to reflect the research insights.

More about our prospective student user journey maps

This post is part of a series: