Seeing Everything in Green and Red Can Lead You Astray: Unpacking the Complexities of Green Hosting Providers

Choosing a green hosting provider is a great way to improve your digital sustainability. But, as I’ve found out, this is only one part of the puzzle towards responsible digital ownership. Read more to understand the complexities behind a green hosting certification.

With global data use skyrocketing, the push to decarbonise the digital industry is more crucial than ever. For website owners, choosing a green hosting provider is an easy way to reduce digital emissions—potentially cutting website-related emissions by 9%.

Our work with Little Forest, developing a digital sustainability tool, has revealed the complexities involved with classifying a hosting provider as green, and the misconceptions behind this. To learn more about that read the blog: It’s not only about the carbon emissions: Using insight to get meaningful and useful sustainability metrics.

This blog covers:

- A background of hosting and the complexities involved.

- What a green hosting provider represents and the difficulty of currently being 100% renewable.

- Why it’s important to understand more than the certification.

- Why sustainability is never a tick box exercise and should be continually integrated into our ways of working.

What do these “green hosting providers” actually do?

Here are a few facts that might leave you wondering what “green” really means in the world of big tech:

Green Energy

Google Cloud has proudly matched 100% of its energy use with renewable sources for seven years straight. (great right!)

But, in 2023, Google’s carbon emissions from electricity hit 3.4 million tonnes, a 580% increase from 2017, when they first hit that 100% renewable milestone.

So how does a company using all renewables end up with 6x more emissions?

Efficiencies

Cloud hosting (used by Google, Amazon, and Microsoft) is super energy-efficient when it comes to hosting data. (great again!)

But around 90% of data stored in data centres is “dark data”, stuff that’s collected and kept but never actually used. That’s 1.3 trillion gigabytes of useless data generated globally every day.

So we are efficiently hoarding rubbish.

Water Usage

Amazon and Microsoft have pledged to be Water Positive by 2030, meaning they’ll put more water back into the environment than they use. (So now data centres can create water?)

In 2023, Microsoft’s data centres used 7.8 million cubic metres of water—that’s 23% more than in 2022, and 64% more than in 2021. Amazon’s water use is rising fast too.

So what is it? Are these companies acting with or against the environment? These facts aim to show how difficult it is to label a hosting company green. I find them slightly comedic, but ultimately it’s really confusing!

So it isn’t that simple…

With pledges and impressive claims flying around, it can be good to have trusted third parties to help distinguish real eco-friendly practices from greenwashing.

The Green Web Foundation (GWF) maintains a directory of green hosting providers that meet stringent criteria. These companies must provide continuous up-to-date evidence that they avoid, reduce, or completely offset their carbon emissions.

This certification is a crucial tool, especially for the work I have been doing; it’s also the first step in a understanding and implementing digital sustainability measures. It’s important for both consumers and businesses to delve deeper and understand the broader impact of their digital infrastructure choices.

This blog aims not to criticise the Green Web Foundation or any specific hosting provider. Instead, it seeks to shed light on the complexities hidden behind simple labels like ‘green’ or ‘red’ and how green hosting can’t be used as a silver bullet.

A quick background on hosting

All digital information (websites, images, Netflix viewing history, your angry birds high score from 5 years ago, everything) is stored on servers, in massive data centres. There are over 10,000 worldwide with half of them in the US.

And they look like this:

A Data Centre

The 2 types of hosting technology:

Traditional Hosting

- Data is stored in a single data centre, offering better security but lower efficiency and flexibility.

Cloud Hosting

- Data is stored and shifted across multiple global data centres. These data centres often partner with Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) to temporarily store data near users. For example, if your website is hosted in Frankfurt, but someone in Ireland visits, the data might come from a nearby CDN in Ireland. This reduces the distance data travels, lowering energy consumption and carbon emissions. This distance is also called ‘megabyte miles,’ a term coined by Tom Greenwood.

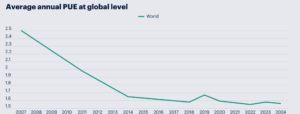

- Cloud hosting also improves internal efficiency, measured in Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE). A PUE value of 1.0 is perfect, indicating that every kilowatt of energy consumed is used purely for computing, without any waste.

Below are some PUE figures for the largest hosting providers:

- Google Cloud Service: 1.10

- Amazon Web Service: 1.15

- Microsoft Azure: 1.18

- Average data centre: 1.56

Of course, there’s lots of complexity behind these numbers too! They vary depending on data centre location, season and even time of day, meaning these values stated are yearly global averages.

So, choosing a large cloud hosting provider brings considerable efficiency benefits, ultimately helping to reduce your carbon emissions. Or does it…

The rebound effect

As efficiency improves, the price of storage decreases, leading to increased data consumption—this is known as the rebound effect (Jevon’s Paradox).

This is especially obvious with data use: it now has such a low impact that it’s super easy to consume without a second thought.

However, efficiency gains inevitably slow down; we can only get so close to a value of 1.0, as seen below. Yet the ever-increasing consumption of data will continue. That’s why I personally don’t love relying on efficiency as a metric for sustainability—it can often obscure the larger issue of responsible data usage.

The average annual PUE at a global level since 2007

Defining green

Data centres run on the energy mix of their local electricity grid. Renewable energy is variable—solar doesn’t work at night, and wind fluctuates. Storage solutions are improving, but full secure decarbonisation isn’t yet feasible in most countries. You can check the makeup of different electricity grids at Electricitymaps.com.

This means it’s much easier to run a green data centre in Iceland than India as you don’t need to offset as much carbon. This brings up conflicting problems for sustainability and data justice, but that’s an issue for a whole other blog.

So, data centres usually rely on fossil fuels in some shape or form to be fully operational, especially in developing countries. A green hosting accreditation from the Green Web Foundation needs evidence of one of these practices:

- Avoid – Run on 100% renewable power, or are operating in regions where the grid is overwhelmingly powered by renewable energy.

- Reduce – This is when you still use fossil fuel electricity from your local grid, but account for the emissions of this energy by using vehicles like a green tariff or environment attribute certificates.

- Offset – This means you still use fossil fuel electricity from your local grid, but account for the emissions of this energy by purchasing quality carbon offsets from a reputable provider/marketplace.

Read more about this on the webpage: What we accept as evidence of green power – Green Web Foundation

The key point is, fossil fuels are often still used and can fluctuate a lot (especially with a global audience).

The bizarre case of a CDN

So, a CDN can reduce ‘megabyte miles’ and, by extension, lower energy consumption. However, CDNs often face bigger challenges as they’re usually located in less developed countries, where offsetting carbon emissions can be more difficult.

If your solo goal is to achieve green hosting certification —especially if you’re on a budget—you might reconsider using a CDN. While CDNs improve page load speeds and energy efficiency, they also add another layer of complexity when it comes to providing evidence of renewable power. This can make the certification process harder despite the benefits gained.

The best-case scenario would be to use a cloud provider and a CDN that both actively work and commit to offsetting 100% of their carbon emissions transparently.

Yet the distinction between this ‘best case’, a CDN-less green cloud hosting provider and even a green traditional hosting provider is invisible when they are all just labelled as ‘green’.

Each of these hosting options has its own strengths, making them useful for different needs – from hosting central AI models to supporting websites accessed globally. But the point is, there is much more behind the term ‘green’. We must be wary of treating digital sustainability as a mere tick-box exercise.

The big green companies

Certification systems can also favour large hosting companies like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft. These giants prioritise rapid expansion, building more data centres to support technologies like AI, cryptocurrency and to manage vast amounts of data.

They then try to balance their environmental impact by investing in renewable energy projects afterward. But this approach of ‘growth first, offset later’ is controversial. The construction of data centres and renewable energy projects requires rare earth metals and minerals, making these activities resource-intensive. And all this expansion to accommodate what is effectively 90% waste?

These companies offset on a market basis, which is common for renewable energy management. But this means that a wind farm in Scotland can be used to offset a data centre in Indonesia. This practice not only raises serious questions about geopolitics and environmental justice, but it also shows how the environment is treated like it’s just an unlimited resource, focusing only on the carbon figures and forgetting about its local value.

This begs the question: Are they really helping the planet, or is this just a way to appear environmentally friendly while prioritising growth? Are these really ‘green’ or sustainable ways of working?

It isn’t a silver bullet, unfortunately

The Green Web Foundation’s certification, much like that of B-Corp and Fairtrade aims to help improve transparency and inform consumers about the importance of ethical practice. They should be treated as stepping stones towards action rather than a complete job.

Working sustainably doesn’t stop at a certification but rather needs to be ingrained into our ways of working.

Sustainability also involves tackling complex issues like water usage, the mining of rare earth metals, and the broader implications of energy politics and data justice. These factors remind us that the challenge of true sustainability extends far beyond net-zero or certifications.

So, even if your hosting is super-efficient or green hosted, remember that your choices still matter! This is just one piece of the puzzle in the sustainability journey.