A human approach to University web estate governance built on collaborative research

Over the last 2 years, I have been conducting important research which delves into the complexities encountered by our University community when seeking a website. By pinpointing key challenges and collaborating with University staff, the Website and Communications team have been rethinking our approach to web governance. This blog sets out the key steps in my research, what I found out and where this has led our team.

A 2018 audit helped me to better understand the size and shape of the University’s web estate

As a starting point, to better understand our web estate, I consulted an audit from 2018 which captured and recorded for the first time the size and shape of the University’s web estate. This captured approximately 1,800 websites in the University Web Registry, a tool provided by external supplier, Little Forest. (To note: active management of the Web Estate Registry since 2018 has indicated the number of websites growing and dropping, however it is still not far from the original number).

From the 2018 data, we learnt that our web estate consisted of:

- diverse approaches: only about 13.87% of our web estate exists on our University web platform (EdWeb2). The rest exists out with this platform meaning that there is considerable variation in how different parts of the University manage their web presence, often leading to confusion about identities, responsibilities and maintenance.

- outdated sites: many older websites are not regularly updated, exposing the University to security vulnerabilities and compliance issues, particularly concerning accessibility.

- abandoned projects: out of date/abandoned sites leads to ‘digital fly-tipping’. This not only tarnishes the University’s image but also raises concerns about sustainability – both environmental and economical.

The data also highlighted gaps in our understanding of our web estate, particularly in relation to how researchers create and use websites to communicate their research progress and outputs. Such websites are being continually developed and make up a significant portion of non-EdWeb 2 websites, but the drivers behind this need were not fully comprehended.

Initial research objective

My initial research objective was to find out, ‘How can we help researchers make the best decisions and choices when thinking about a website for their research project?’

I chose this as my objective because I wanted to understand more about the needs and problems experienced by the research community. Through this understanding the hope was that this would help us improve the long-term health of our web estate.

A project to research the needs of colleagues who own or want to create a website was kicked off

The goal was to understand the key motivations for having a website, and the steps involved in achieving this.

User research approaches – journey mapping and interviews

My research started by posing the fundamental question many researchers ask: “I want a website, how do I get one?” This led me to map out the specific steps a researcher takes when considering a website to give me a detailed insight into the following questions:

- Is the journey the same across the University? If not, where does it differ?

- What were the obstacles or challenges?

- What questions did researchers have and who did they speak to?

- What help, guidance and support did they expect the University to provide?

You can find out more about journey mapping and what it is on the Nielson Norman website.

Journey Mapping 101 – Nielson Norman Group blog

Engagement with Schools, Colleges, and departments to understand the diverse needs across our University

I conducted journey mapping with 21 members of staff including researchers, research support staff, communications and marketing professionals, IT leads, technical developers, digital content officers, and research facilitators.

This research involved three stages:

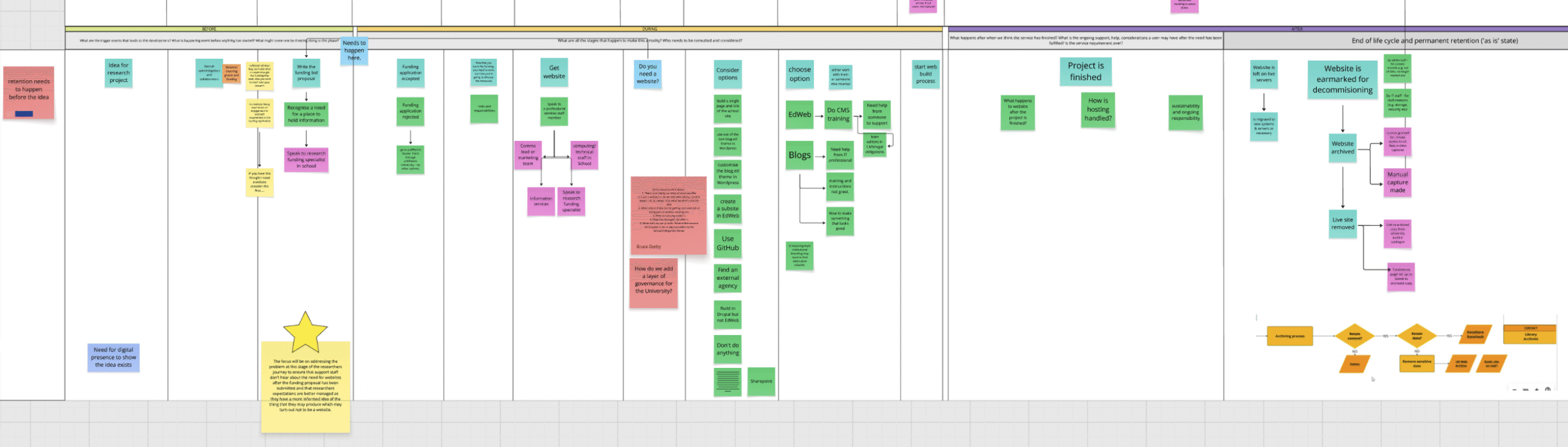

Stage 1: Initial mapping with groups and individuals allowed me to capture the end-to-end steps experienced by those participants. This resulted in the creation of six separate journey maps.

Stage 2: Iteration and refinement with participants enabled me to combine the steps from the multiple journey maps into a singular map. This was used to bring together the core steps as well as identify other information related to the people, processes, services and technologies required at each step. The single unified map combined common patterns as well as discrepancies.

Stage 3: Final validation of the single unified map against a variety of use cases allowed me to test the end-to-end journey ensuring its accuracy and validity. It exposed the entire lifecycle of web-related activities starting with the initial thoughts around the research project, leading up to the website request and the final stages after project completion.

This comprehensive mapping helped capture a full spectrum of experiences and needs from both researchers and support staff, illustrating the processes that facilitate website development needs and support to mange this.

Final end-to-end journey map highlighting the key stages.

Key insights from journey mapping

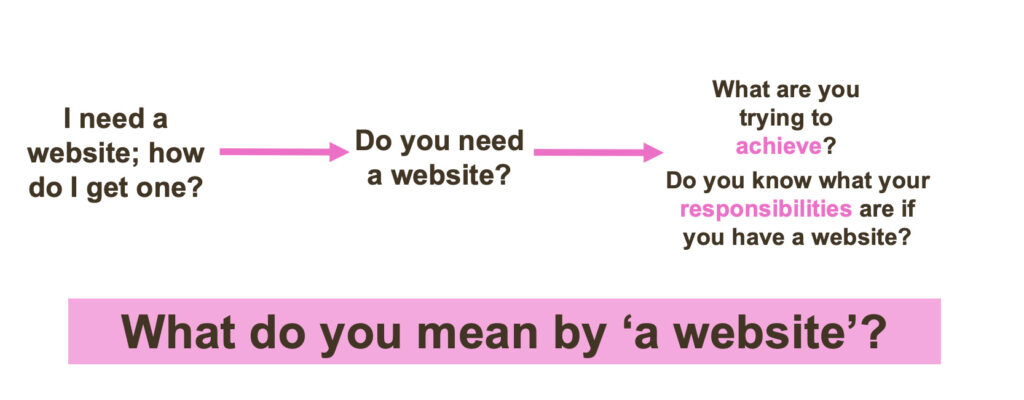

Journey mapping revealed that the question “How do I get a website?” typically arises midway through the researcher’s journey, often after funding has been secured and allocated. However, professional services staff supporting these researchers noted that this timing is sub-optimal for making informed decisions about digital resources.

There’s a strong need to initiate these conversations earlier, ideally during or before the funding application process. Such timing adjustment would better manage expectations regarding available digital options, associated costs, and responsibilities, providing researchers with a clearer understanding of the choices that best align with their research goals.

As well as the timing of the question “How do I get a website?” being important, the findings also suggested perhaps the focus of this question should shift to “Do you need a website?” It may be that there is another communication method or online presence that better suits the researcher’s needs.

This change highlights the importance of considering alternative digital solutions that might be more suitable but are often overlooked because they’re not discussed early enough in the research project life cycle.

Reviewing research applications for clarity and expectations

Together with my colleague Alice Austin, the University’s web archivist, we analysed 20 successful research applications. Our review revealed a common vagueness in how researchers articulated their needs and intentions for websites. Often, it was unclear what type of website was needed or why.

Moreover, we noted unrealistic expectations regarding the level of available University support. There was an assumption that because the University already has the necessary infrastructure and technical expertise to build and maintain a website, such outlays didn’t need to be accounted for in research project budgets. Therefore, most successful research applications we reviewed didn’t explicitly mention website costs. For those who did, there was a wild disparity in estimated costs (ranging from £60 to £30,000 per year), often linked merely to administrative assistance needed for updating content rather than comprehensive site management.

Of the research applications we analysed only 25% eventually led to the creation of a standalone website with a dedicated domain.

This observation raised important questions about the real necessity and strategic planning behind these website requests.

Evolving our approach to website needs

These findings prompted a pivotal shift in my approach. Moving from asking “How do I get a website?” to “Do you need a website?” This shift helped reframe our subsequent user research and drove the focus of our collaborative co-design workshop, aiming to better align digital resources with research needs and goals.

In-person co-design workshop

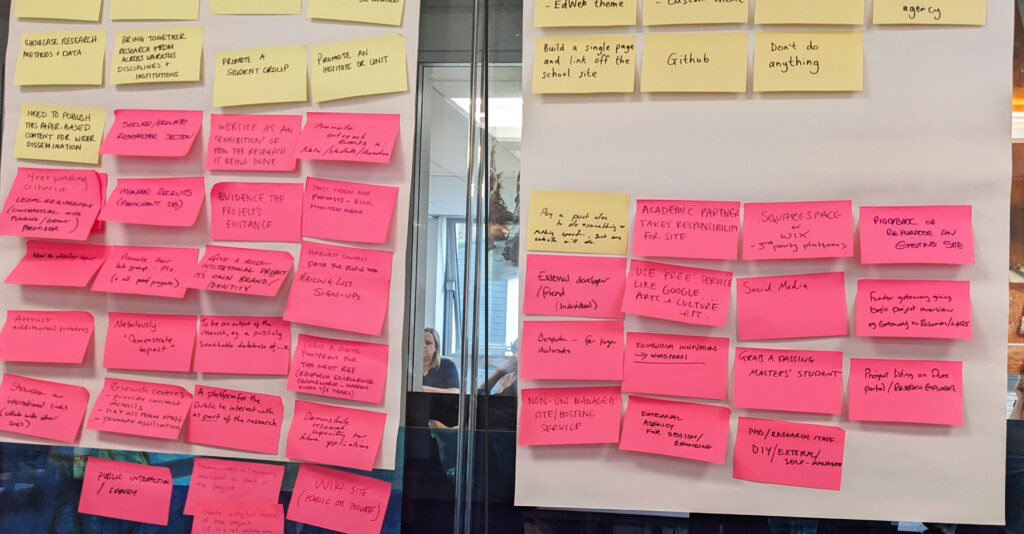

The co-design workshop aimed to delve deeper into the necessity of websites within research projects, exploring key questions like: “Is a website always the appropriate solution?” and “When might creating a website be detrimental?”

To tackle these questions, we welcomed 18 participants from across the University, including both researchers and professional services staff, some of whom had participated in the earlier research phase.

Working in groups, participants first looked at identifying the needs of researchers and the options they may consider. This was followed by brainstorming potential solutions and sketching out ideas to assist researchers in making informed decisions about their online presence.

Post-it notes identifying research projects needs and options

Key outcomes from the co-design workshop

The workshop facilitated in-depth discussions, helping to refine further my research objectives. I recognised that to adequately respond to “Do you need a website?”, researchers must first articulate their project aims and identify their audience/s. This clarity is crucial for accurately defining their digital needs. Furthermore, researchers need guidance to understand the responsibilities associated with creating a website and this was a theme which was repeatedly mentioned throughout the workshop.

How the research question evolved and was reframed at each stage of the project.

The importance of addressing these issues early in the research funding application process was emphasised as well as engaging with support staff from relevant departments to ensure well-informed decisions could be made. These discussions helped to further inform our thinking around what people actually mean when they say they need a website – as it may in fact be one of a range of more diverse online solutions they need such as a blogs, Sharepoint sites, social media accounts or event ticketing platforms.

It became apparent that the term ‘website’ was frequently used to describe various forms of online presence, not just websites in their traditional form.

This further informed the research objective outlined at the start of this project, which evolved from being ‘How can we help researchers make the best decisions and choices when thinking about a website for their research project?’ to a stronger emphasis on thinking about their research project’s online presence.

The research objective was reframed as, ‘How can we help researchers make the best decision and choices when thinking about their research project’s online presence?’

The next steps involved translating this objective into practical, centralised guidance and support for both the research and non-research communities at the University.

Launching a new web governance resource

Building on the research and the reframed research objective we have embarked on a project to gather all relevant policies, guidance, advice and information related to web governance at the University into a single location. We will be introducing a Web Estate Governance SharePoint with the aim to cultivate an awareness of and appreciation for the importance of maintaining a secure and compliant digital presence, which also highlights the amazing and innovative work happening at the University.

We will follow a phased delivery of the SharePoint resource, with the intention to first launch information on key responsibilities for those thinking about creating or managing an online presence.

These key responsibilities cover:

- Accessibility

- Archiving and preservation

- Brand

- Content creation and maintenance

- Copyright

- Digital sustainability

- Data protection

- Information security

- Website addresses, URLs and domains

- Website hosting and technical maintenance

This content have been developed alongside various University subject matter experts and following feedback from the University’s Web Governance Group.

Katie Spearman, our content designer in the User Experience (UX) Service, showcases how she has worked to create the Web Estate Governance SharePoint ensuring it follows content design best practice in her latest blog post:

Putting content design theory into practice for the new Web Governance SharePoint

As the development of this SharePoint resource progresses, we will continue to actively engage people in our process. The next step involves conducting usability tests on our key responsibilities content with University staff prior to its launch.