Adapting our transport systems for a changing climate

Siôn Pickering, our Projects Coordinator for climate conscious travel, explores how our transport systems need to change in accordance to the more frequent extreme weather events.

I think we can agree that climate change is real and it is happening right now. How far you agree that humans are causing it, is up to you. We are a species that learns to adapt. Sometimes this adaptation takes time. Sometimes this adaptation needs to be quick.

Quick changes always feel harder to make. We can feel out of control. It is this control that leads to further indecision, further loss of action, further delay.

Adaptation

Adaptation to climate change is something that is often seen as a process which has time. The climate has been changing for thousands of years, we don’t need to rush our adaptation to climate change. The problem is that we have already used up a lot of the available time, and the impact we as humans have on speeding up climate change means that we now need to make changes quickly.

In this article we’ll focus on the impacts of climate change on our travel and how we might need to adapt. I’m writing this during the Covid-19 pandemic, where travel has been curtailed somewhat. “Problem solved” you might think. But Covid-19 will not stop our travel indefinitely, so think of this as looking into the future a few years, in a world post-Covid-19, where we have done little to change our collective travel habits.

Currently travel is a huge part of our lives. On a regular basis we might jump on a bus to work, drive to take children to school or to pick up food from the shop. Less frequently we might travel by car or rail to visit family or friends across the UK, or take a flight for holidays abroad. For many of these we might think of the impact that climate change will have on a local scale.

We can also become more adept at reducing our reliance on personal travel. If we start to see it as a luxury rather than a necessity – whether we are commuting to work or traveling abroad to soak up the sun – then we start to live without the need to travel.

For example, if flood risks are heightened, does this increase the likelihood of damage to road and rail provisions? The answer is yes – just look at the damage caused recently where a prolonged period of heavy rain caused roads to be washed away, bridges to be damaged and, I write this very much with a heavy heart, lives to be lost as a rail service in Aberdeenshire was derailed.

If sea levels rise, what does this mean to our coastal transport links? Some estimates suggest that the sea levels could rise by as much as a metre by 2100. This might not sound a lot, but would have significant impacts on things like coastal erosion. Thinking of the east coast train line from Edinburgh to London. There are stretches of this journey which run remarkably close to the coastline. An immensely scenic route for sure, but what changes would we need to make to ensure these lines remain in place?

When we talk about travel, we also need to think about the bigger picture. Travel includes the movement of goods on a global scale. How did those apples make their way to our local supermarket from China, Italy, or America? What about the mobile phone you used to talk to your friend last night? What minerals are used to make the various components and how are these moved through the supply chain before you purchased it?

Transport links in other countries may not be as secure as they are in the UK, and the impacts of climate change may be greater in these locations. I wasn’t going to mention Covid-19 in this article, but in some ways the travel ban that has taken place could be considered an example of what would happen should global movement of supplies break down. We all remember the rush for those “essential items” (of which toilet paper was most in demand). What happens if this becomes the same for other items? Will demand push up prices?

Travel also means providing fuel for our vehicles. In the short term this means petrol and diesel (which we need to import, and travels in tankers via land and sea). In the longer term, the UK is phasing out combustion engines to reduce carbon emissions (with a ban on selling new petrol or diesel is now set at 2035 at the latest). But how is this electricity generated? If we get more extreme weather patterns will this impact how much energy we can produce from water, from solar, from wind? Will it drive up prices meaning only the wealthy can afford to travel or will there be “energy droughts” where we have to queue up outside charging stations to get a few more miles down the road…

These are extreme examples, but ones that are not wholly unrealistic.

How do we adapt?

Unfortunately I don’t have the answer to this. In fact I don’t think we will ever have the golden bullet answer to adapt to climate change without a drastic overhaul of all aspects of our life.

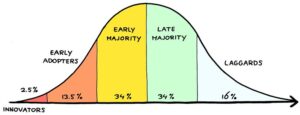

Though it’s not all doom and gloom – making changes as an individual may seem to make no difference, but collectively, such actions are possible. When we think of the innovation curve, we need the innovators and the early adopters to act.

In part, any action we can take is shortening our reliance on long supply chains. We can do this by buying locally, adapting what we eat with the seasons. Purchasing goods second-hand also helps with this, as the travel associated with the item will be much less than if you bought one new.

We can also become more adept at reducing our reliance on personal travel. If we start to see it as a luxury rather than a necessity – whether we are commuting to work or traveling abroad to soak up the sun – then we start to live without the need to travel. In doing so, we are taking the first steps to adapting to climate change. Not only this, we are reducing the carbon emissions associated to our travel, and so reducing our impact on climate change overall.

In some ways, 2020 has shown us what is possible. Where before some companies insisted their jobs couldn’t be done remotely, suddenly so many of us have proved that this is not the case. Could our commuting patterns change for good?

Active transport has also increased, with more of us heading around the city on a bike for our errands. Can we keep this up as we get back to “normal”, whatever that will be? We need support in the form of improved infrastructure in order to achieve this, and – certainly in Edinburgh – this is slowly starting to appear.

Vacations abroad have all but been cancelled, but we still have annual leave to take and, let’s be honest, probably would be glad not to see the same four walls we’ve been staring at since lockdown began. As such staycations have started to boom this year. Whether for a night or a week away, it is amazing what can be found within a short distance of home.

Adapting our travel habits is not going to be easy, or quick. Starting now gives us longer to get it right, longer to adapt and, overall, more control of our situation.

Recent comments