There is a lot of cross-over in my two jobs as Archive & Library Assistant at The School of Scottish Studies Archives (SSSA) and Copyright Administrator working for the Decoding Hidden Heritages Project, as I work with the same collections for both.

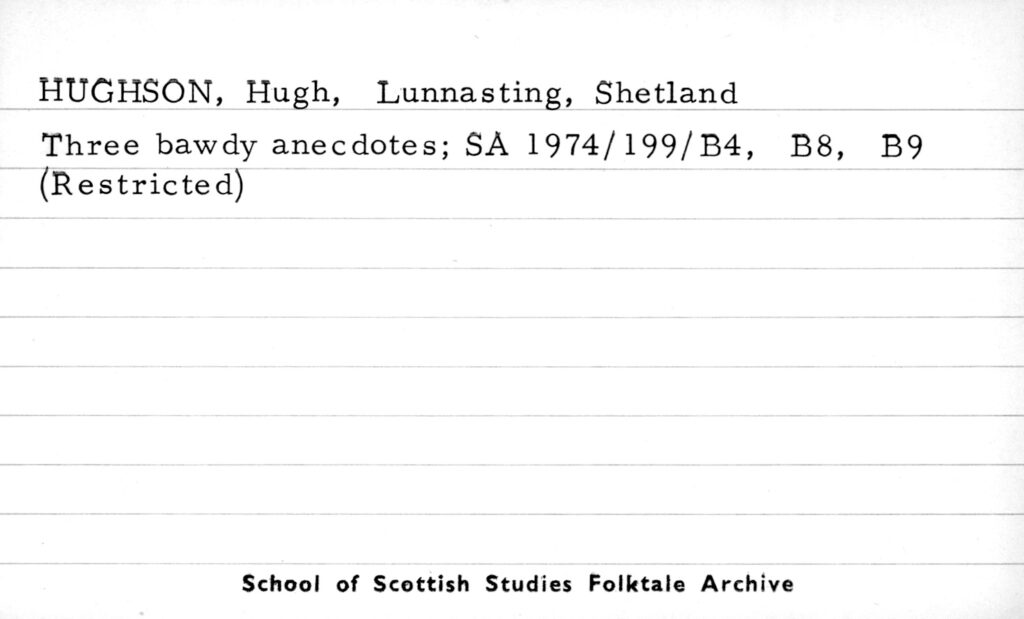

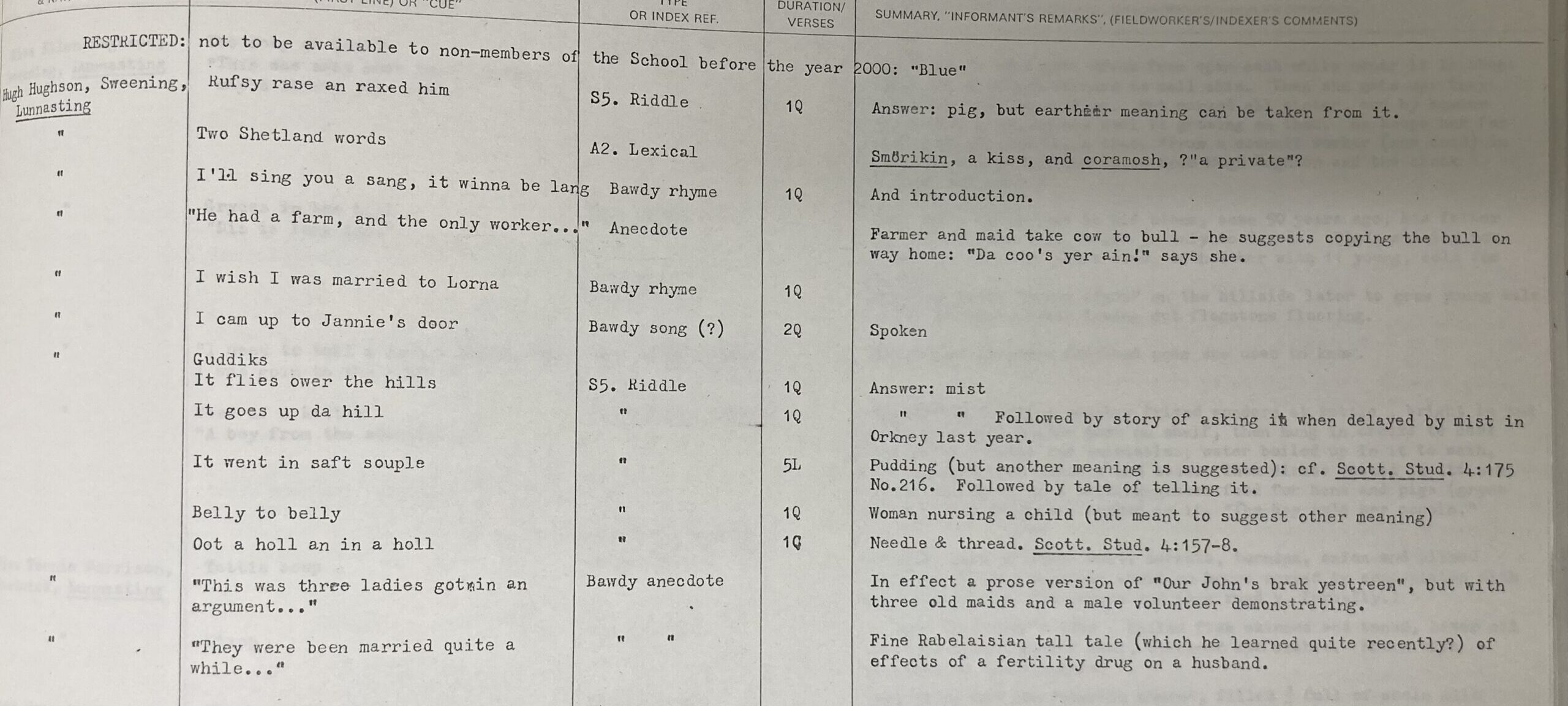

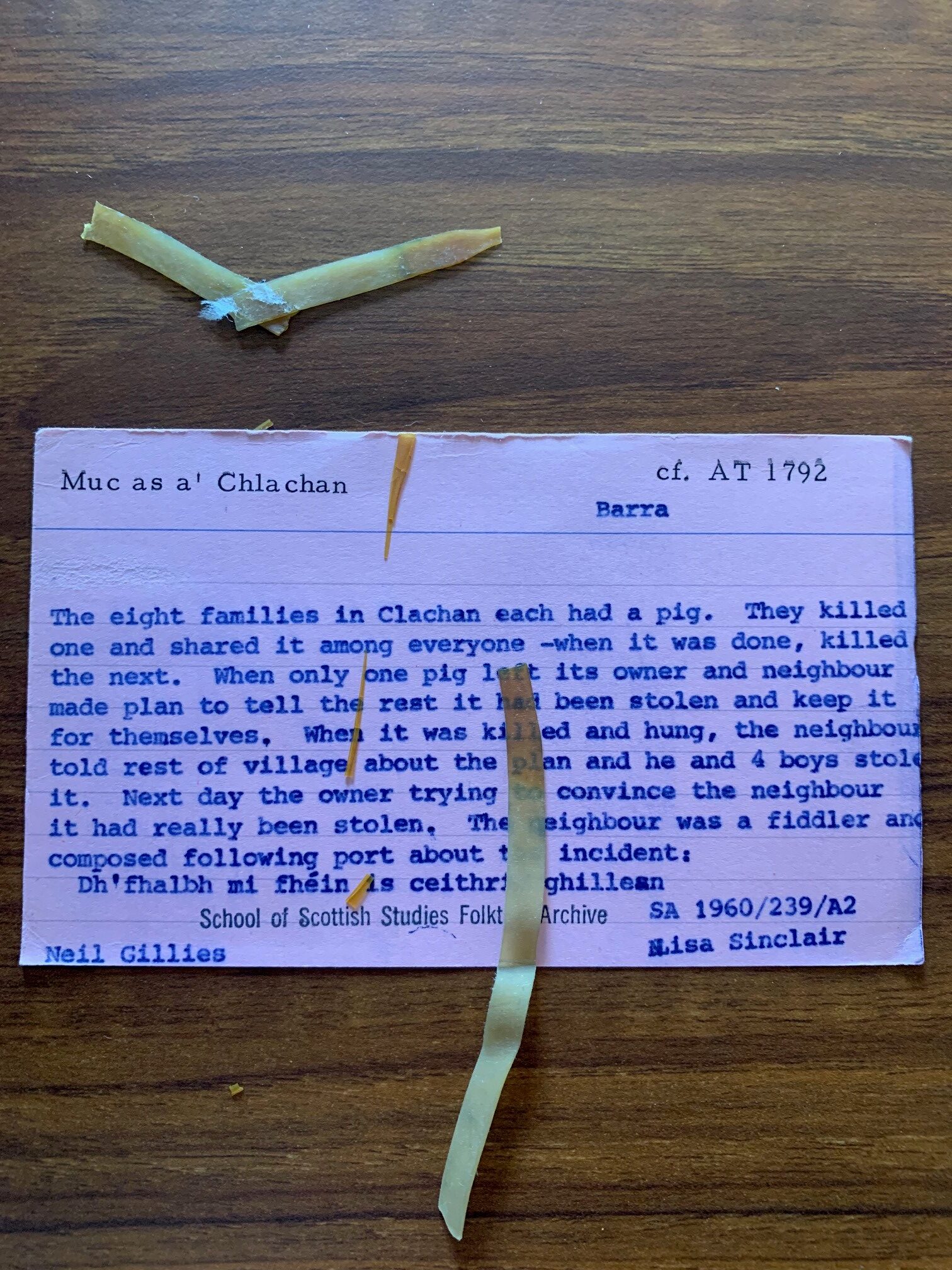

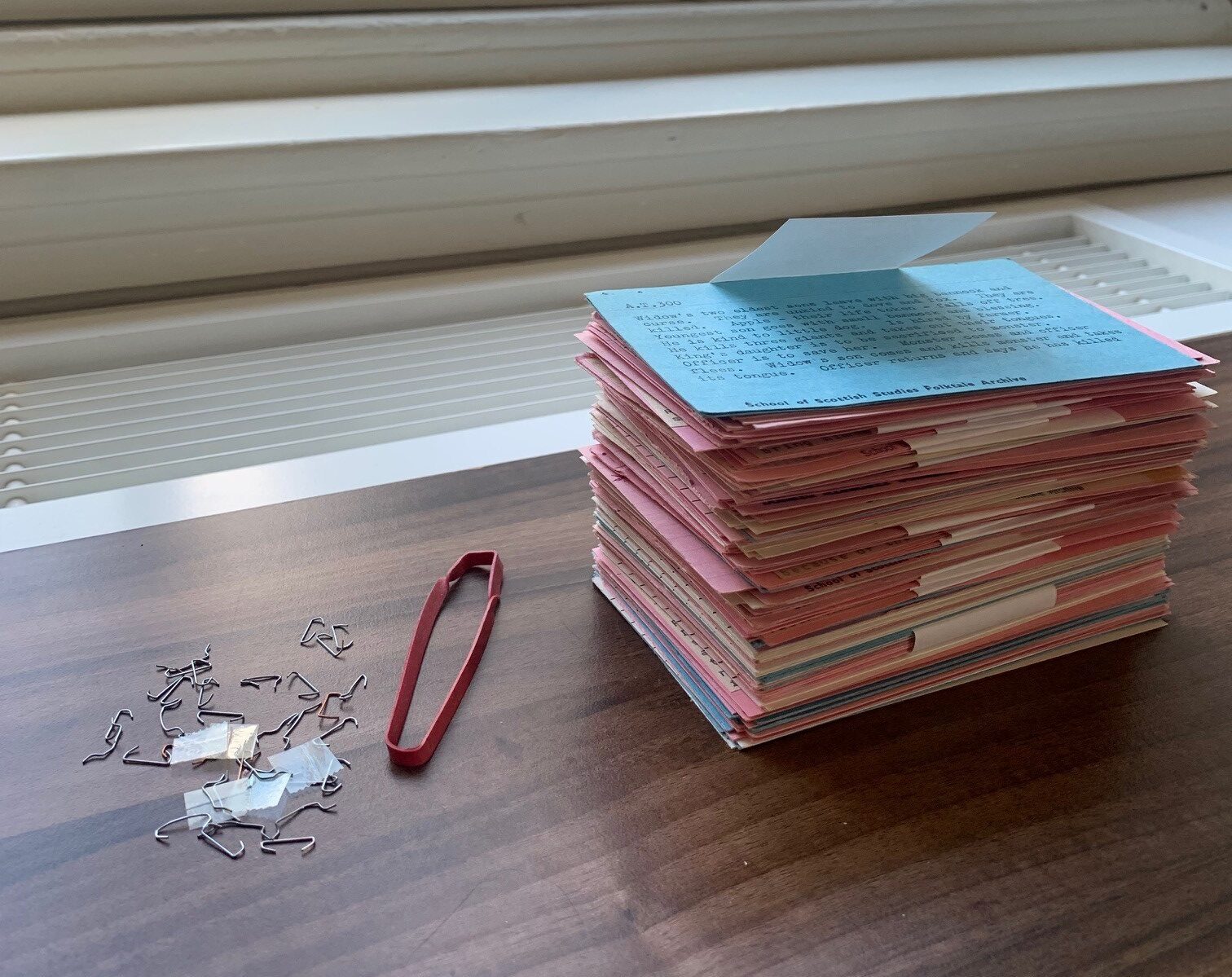

Recently I came across this card from the “Informants index” in the Tale Archive.

It is not unusual to see material restricted in the archive, but many of the closures and restrictions at SSSA tend to be retrospective where we have screened archive material or when we discover ‘special category’ data is discussed. It is slightly more unusual – in our collections – to see material restricted from the earlier days of the School, such as this recording from 1974. As there is the potential that transcriptions of these exist, and that these may soon be digitised and published, it is important to look into this further.

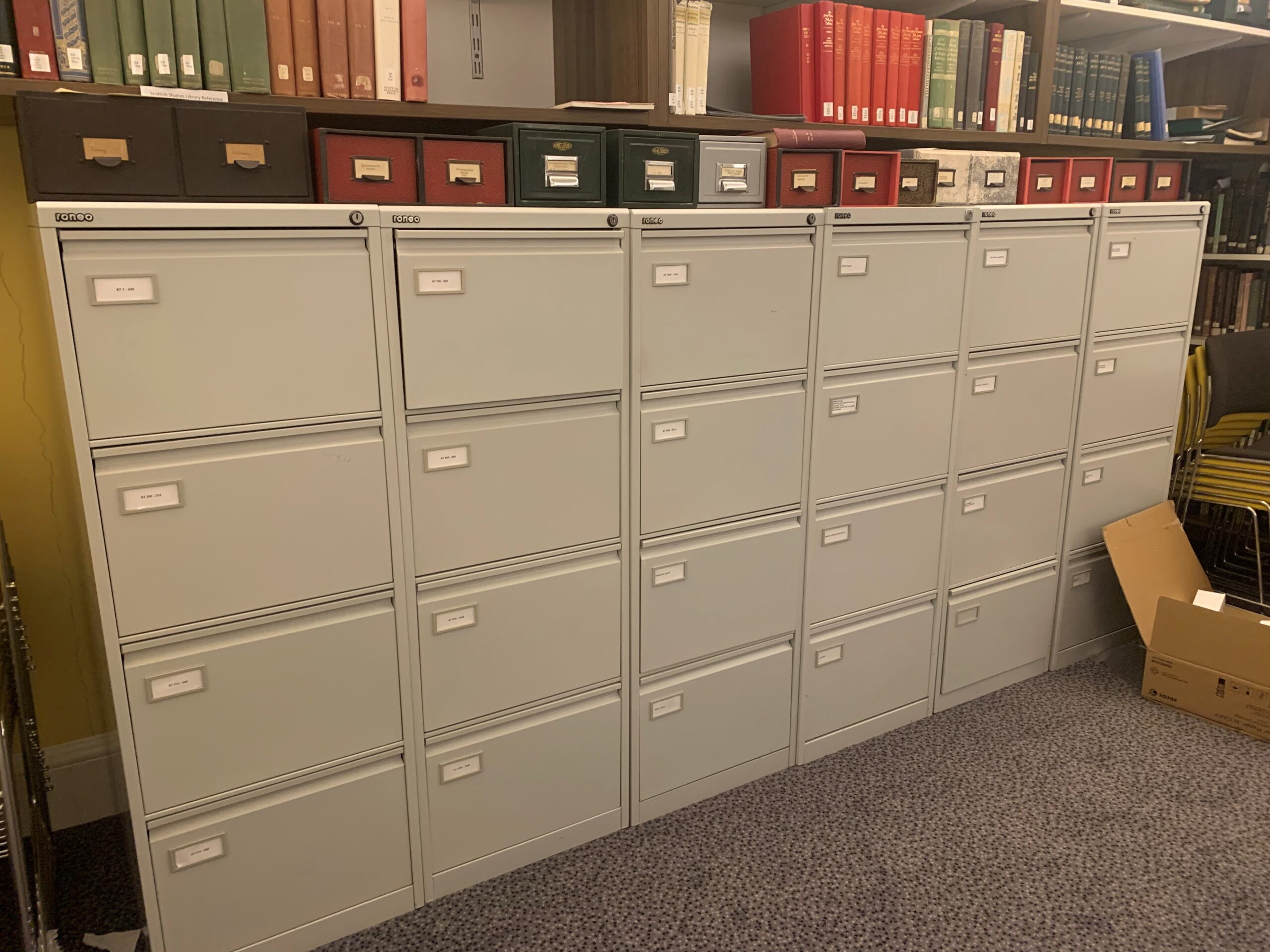

As you may remember from some of my earlier posts, there are several places within the archive to look for further information – the first is the Chronological Registers containing summaries of fieldwork recordings.

RESTRICTED: not to be available to non-members of the School before the year 2000: “Blue”

This was the first time I encountered a restriction from this period with a future date attached. The year 2000 may have been chosen as a date to be sufficient for period of restriction due to a number of reasons, but it seems somewhat arbitrary without any further information. The three bawdy anecdotes are summarised here, along with other bawdy riddles and songs, but there isn’t too much here to tell us about how “blue” it might be.

Something to remember about this point of the history of the School of Scottish Studies was that it was a Research Unit; in the 1970s SOSS had begun to offer undergraduate courses at 1st and 2nd year level and offered supervision for Postgraduate research, but it was not yet established in offering it’s own degree courses and the collections were not widely open for access. However, this notice does suggest that there was – or might be in the future – access to others beyond UOE.

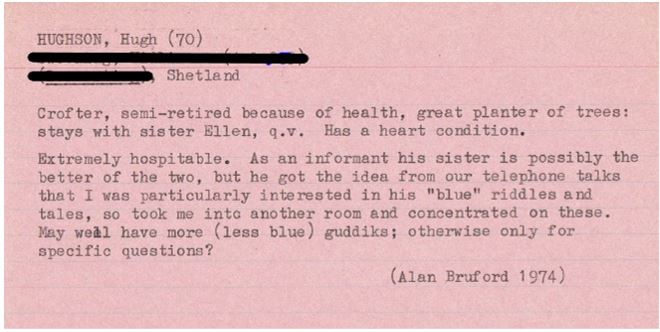

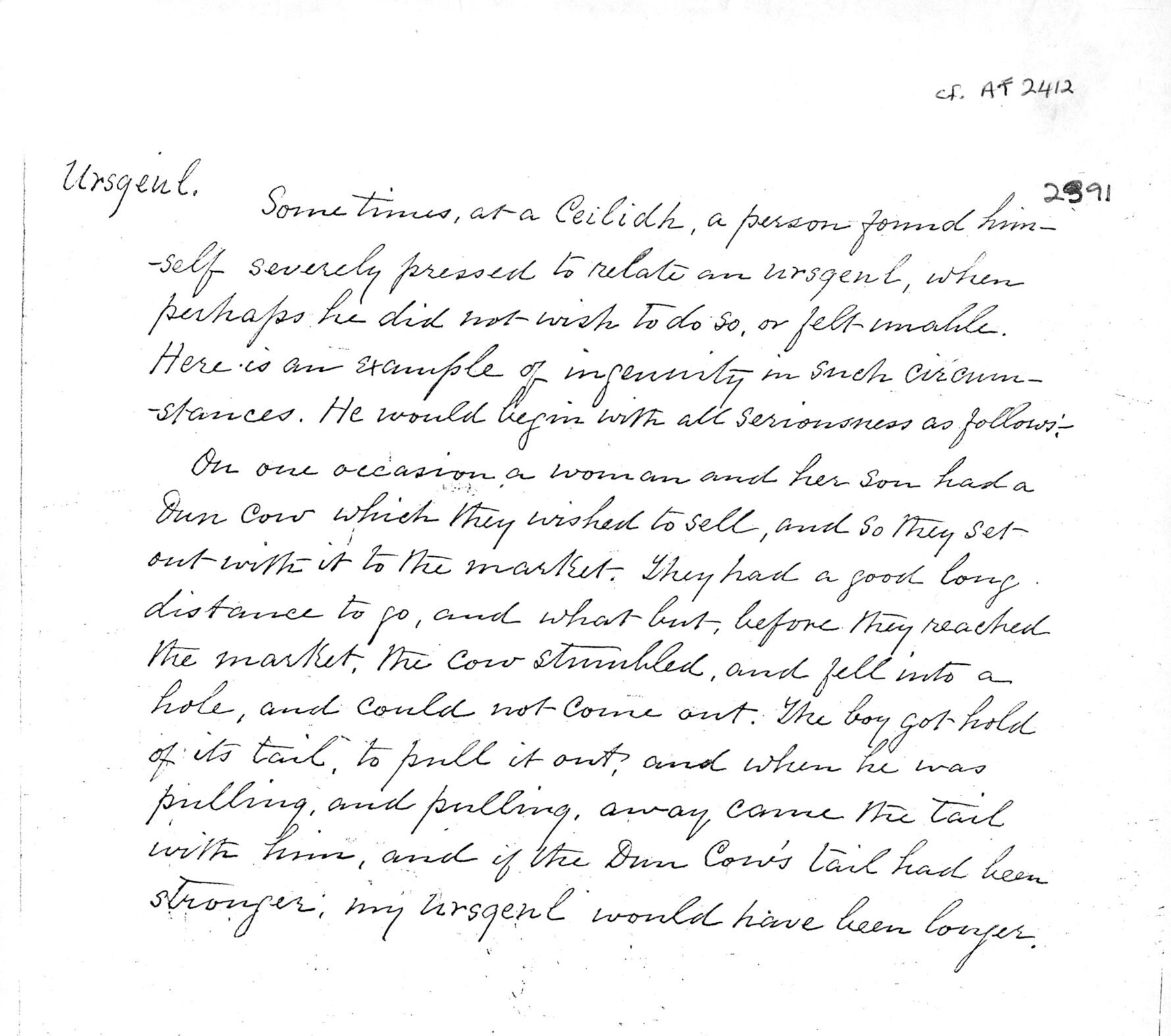

Alan Bruford kept helpful notes on much of his fieldwork and his contributors and so I next checked these to see if there was more information about this contributor, Mr Hughson.

Context is a wonderful thing! As well as giving us information about Mr Hughson’s blue riddles – or guddicks, in the Shetland dialect – this gives such a great insight into how Bruford approached fieldwork – from pre-interview telephone calls, interesting information about the interviewee and the importance of the person’s contributions for the ongoing research at SOSS. It also shows the bonds of trust between fieldworker and contributor, which would seem to be a driving motivation in Bruford restricting the material. There is no further indication why the date was chosen for the embargo, but I think it’s fair to assume it was a point in time in which it was assumed Mr Hughson would have passed away.

I had a listen to the recording itself and the blue material includes three bawdy songs, one which includes a Peeping Tom; an anecdote which infers bestiality (SA1974.199.B4); a story of three women discussing what they think a penis looks like and then meeting a willing man to help them in their research (SA1974.199.B8) and a tale of a fellow who is given medicine to assist with fertility but which has an extraordinary affect on the size of his manhood (SA1974.199.B9).

Of course, we can remove the restriction on this material now (a mere 22 years after it’s intended embargo date!) but we do still have an ethical responsibility to ensure our records are up to date and that we inform our service users that this material may cause potential offence. While this material was intended to be funny by the contributor, there are triggers here for many people in some of these pieces, for example, sexual abuse and unwanted sexual attention. In cases like this, we ensure that we include a text file with the digitised recording, so that staff can flag issues to our readers, before they begin listening. This is something that will need to be considered when making transcriptions and recordings available online.

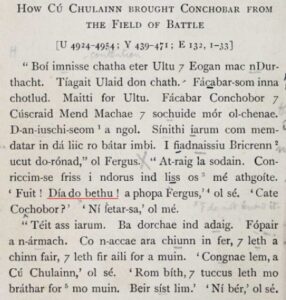

Lorg mi fiù aon sgeulachd far a bheil an abairt ’ga chleachdadh sa chaochladh, ag innse do chuid-eigin nach eil fàilte romhpa ann an àite. Anns an sgeulachd, tha Séadanda dìreach air a’ chù aig Culainn a mharbhadh agus tha Culainn a’ faighneachd dheth cò esan agus nuair a chluinneas e cò esan, tha e a’ freagairt

Lorg mi fiù aon sgeulachd far a bheil an abairt ’ga chleachdadh sa chaochladh, ag innse do chuid-eigin nach eil fàilte romhpa ann an àite. Anns an sgeulachd, tha Séadanda dìreach air a’ chù aig Culainn a mharbhadh agus tha Culainn a’ faighneachd dheth cò esan agus nuair a chluinneas e cò esan, tha e a’ freagairt