Scottish Gaelic, spoken by roughly 60,000 people today, is poised for a technological transformation thanks to the ÈIST project, led by the University of Edinburgh. ÈIST [eːʃtʲ] (‘ayshch’) is short for Ecosystem for Interactive Speech Technologies, and means ‘listen’ in Gaelic. The project is funded by the Scottish Government and Bòrd na Gàidhlig, with key partners including the BBC ALBA, NVIDIA, the University of Glasgow and Tobar an Dualchais / Kist o Riches. It aims to support the revitalisation of the language through cutting-edge interactive technologies, including speech recognition.

Since launching in 2023, ÈIST has focussed on developing accurate speech-to-text for Gaelic, but also for English — to cope with code-switching. The initial aim was to produce a system that could generate Gaelic-medium subtitles for BBC ALBA and Radio nan Gàidheal. In a forthcoming paper, the team reports achieving nearly 90% accuracy for chat shows, news and current affairs programmes. Now the team is expanding the technology, making it suitable for more diverse contexts, ranging from Gaelic-speaking classrooms to old fieldwork recordings.

In the autumn of 2025, the creation of an accessible, robust API (Application Programming Interface) will democratise these tools further. Developers and researchers worldwide will gain access to Gaelic speech recognition, embedding the technology into applications ranging from educational software to digital assistants.

Bridging Linguistic Gaps

Currently, Gaelic speech recognition systems struggle to transcribe younger speakers, whose speech patterns often differ from those of heritage speakers. ÈIST addresses this with its dedicated subproject, Recognising Children’s Speech, which will soon gather data from Gaelic Medium Education schools and units across Scotland. This new data will ensure that the speech of young learners is represented accurately.

The implications of this work are profound. Enhanced speech recognition can transform educational tools, such as TextHelp’s Read&Write, providing more effective support for literacy and learning among children. It can also improve accessibility for Gaelic speakers of all ages, especially those with literacy challenges or hearing impairment, providing critical tools for communication and inclusion.

A Community-Powered Initiative

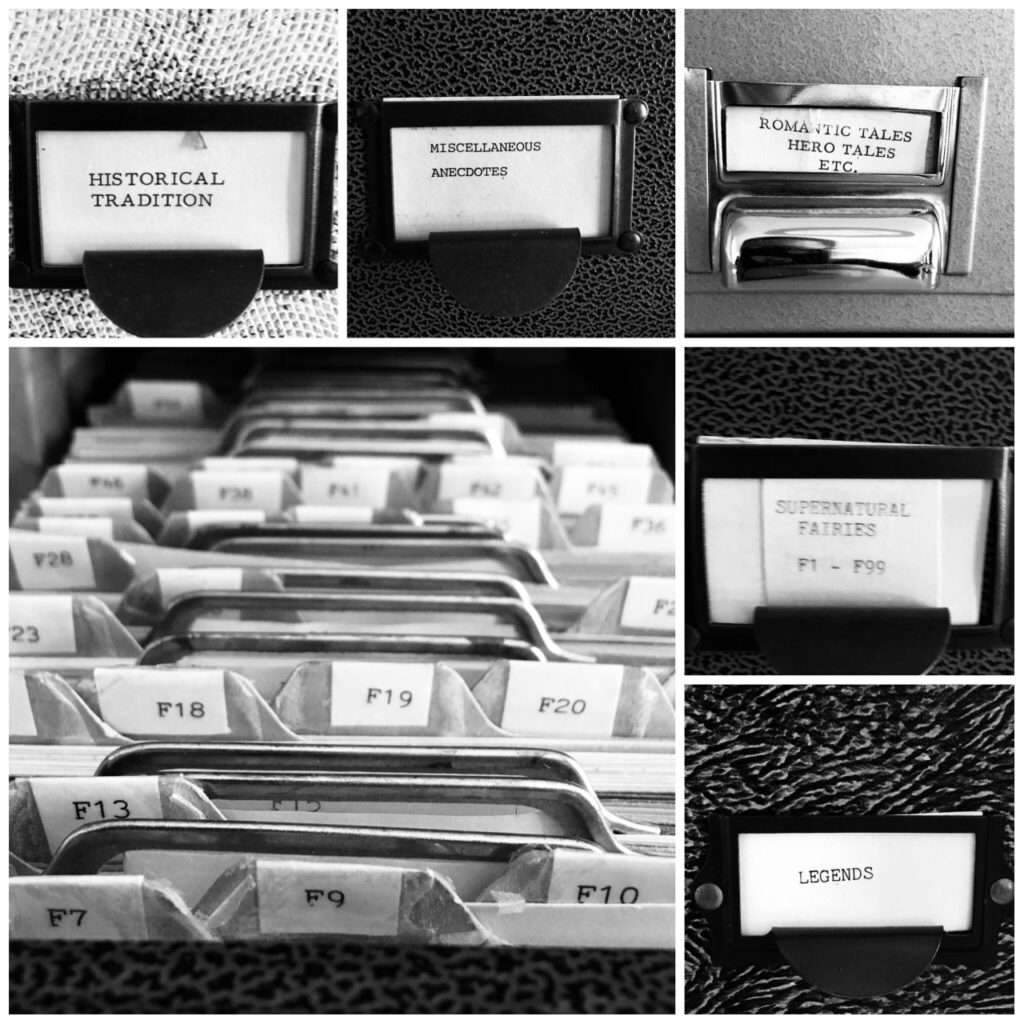

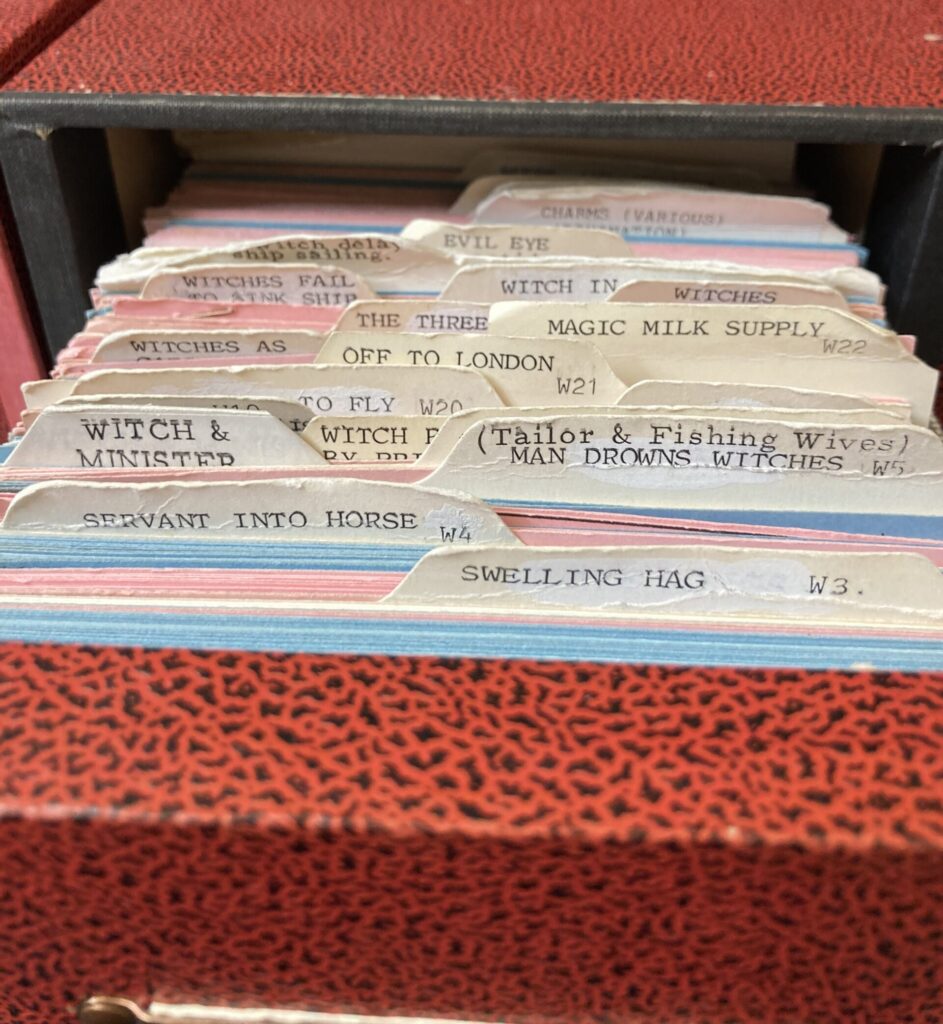

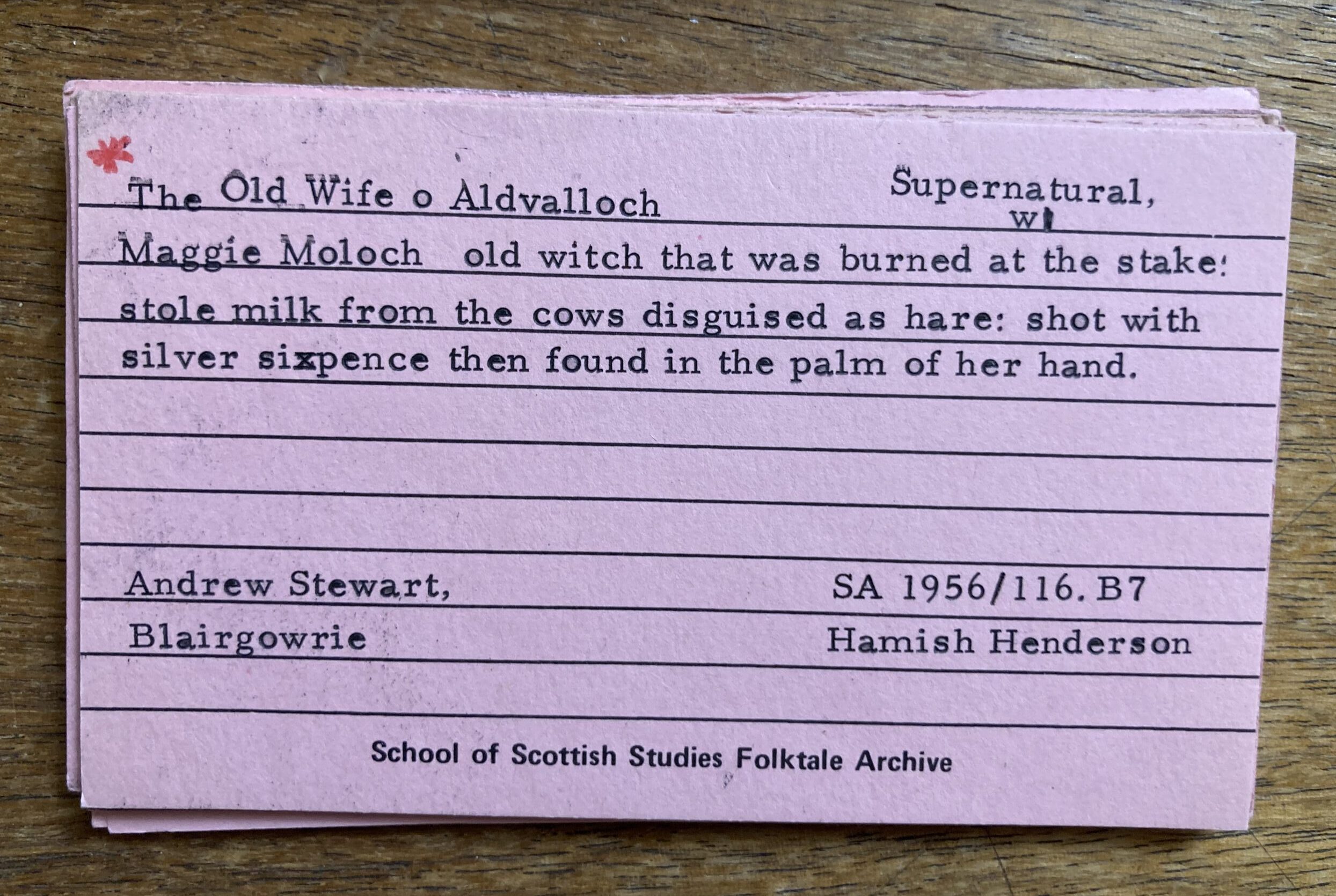

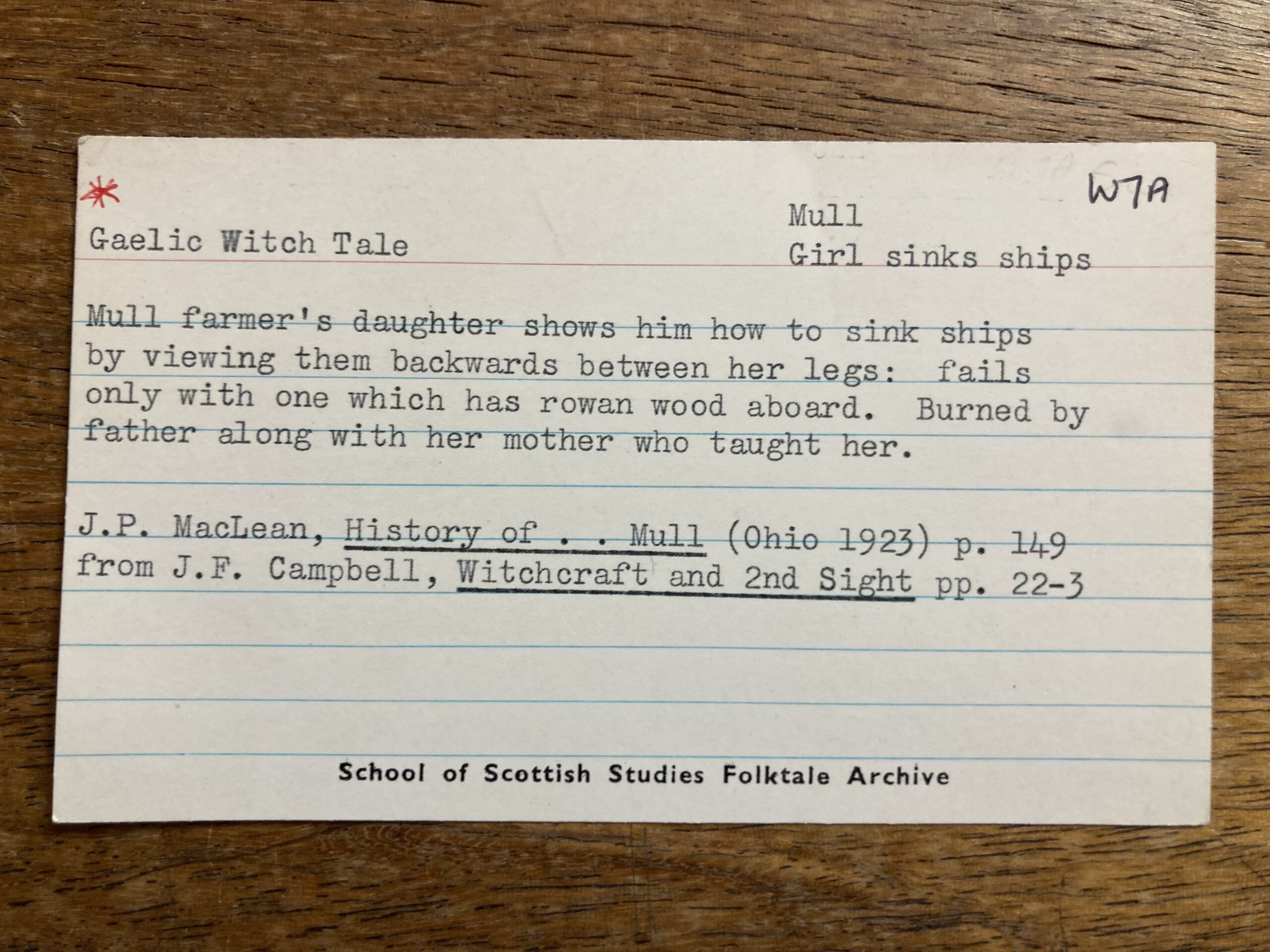

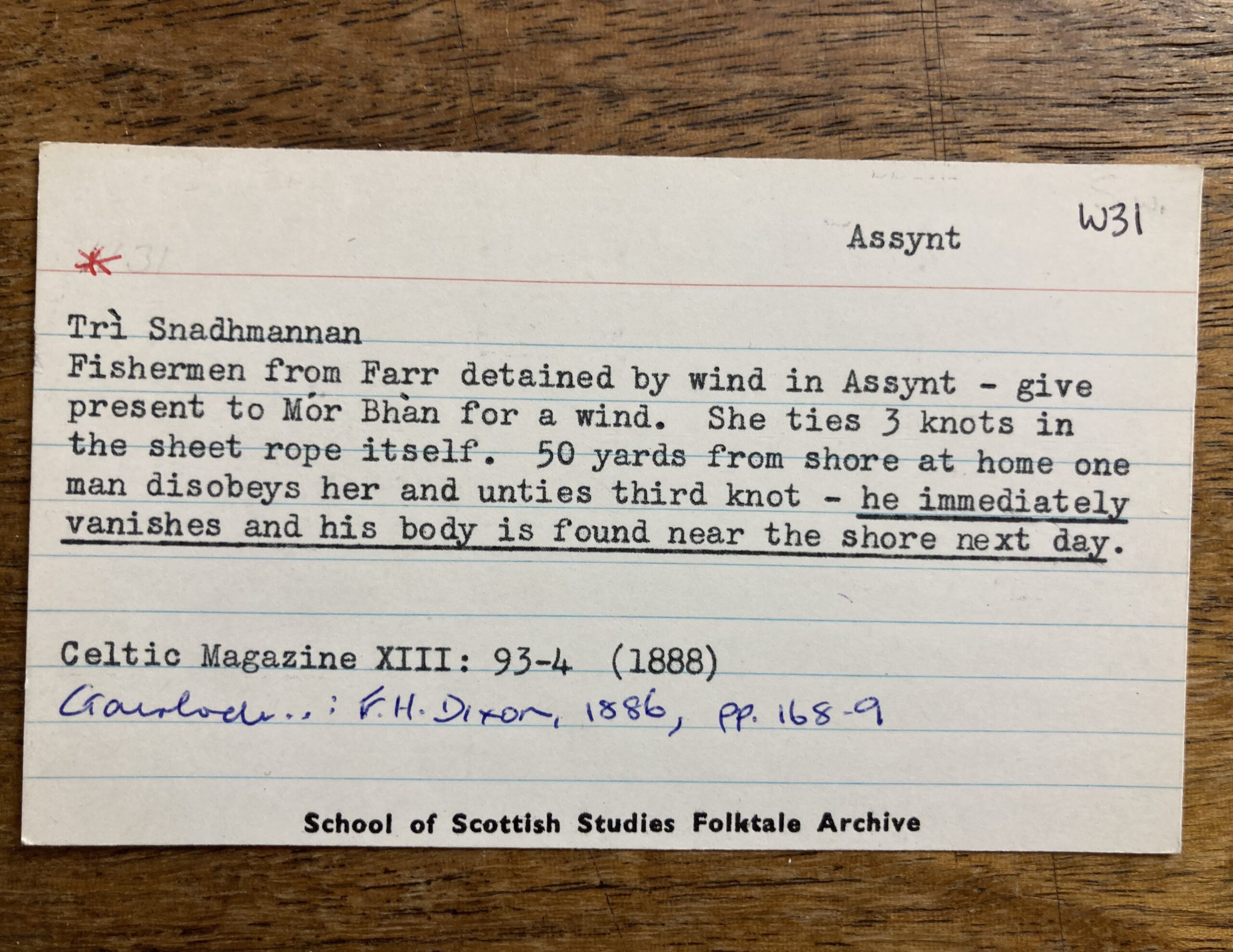

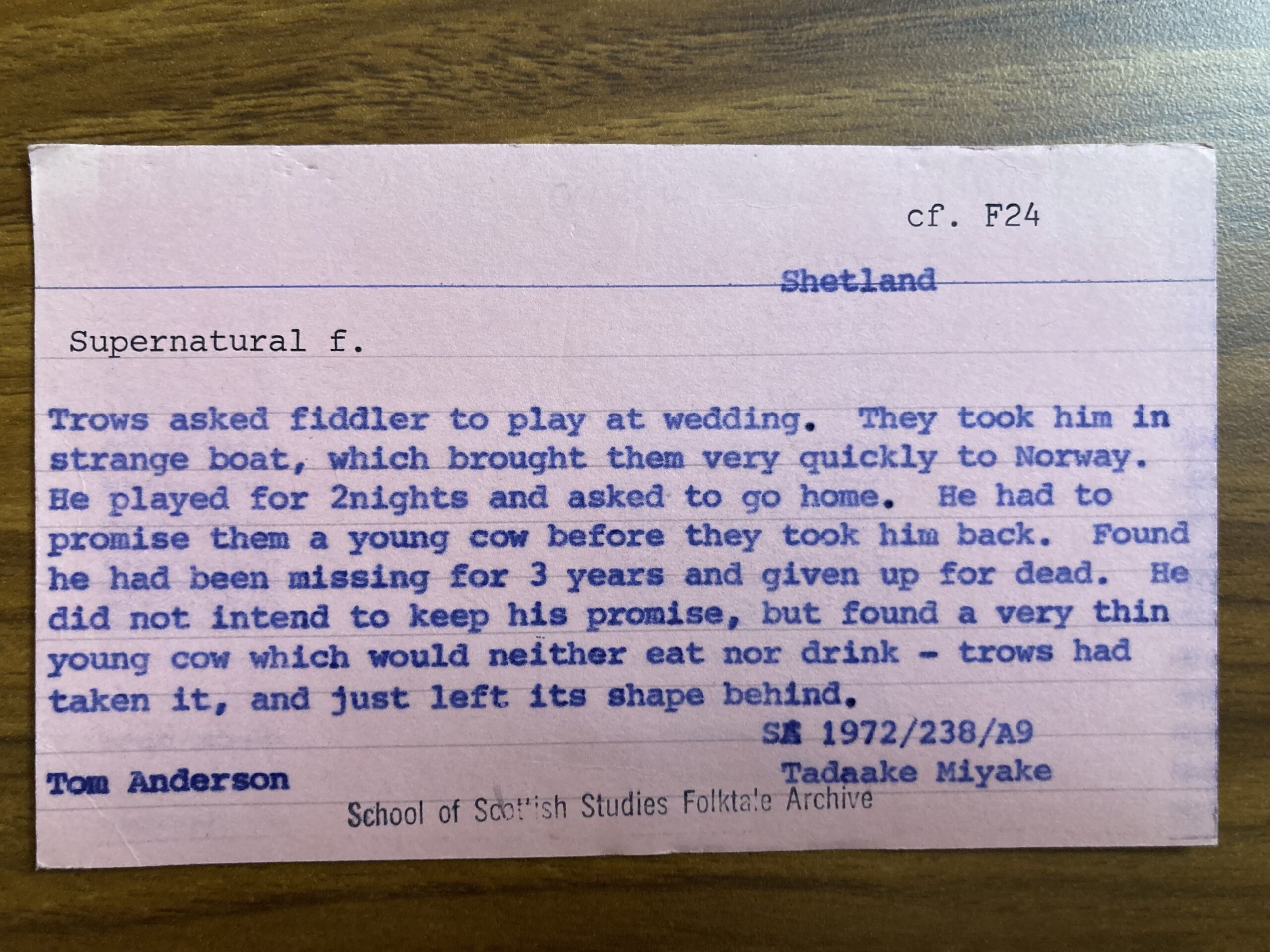

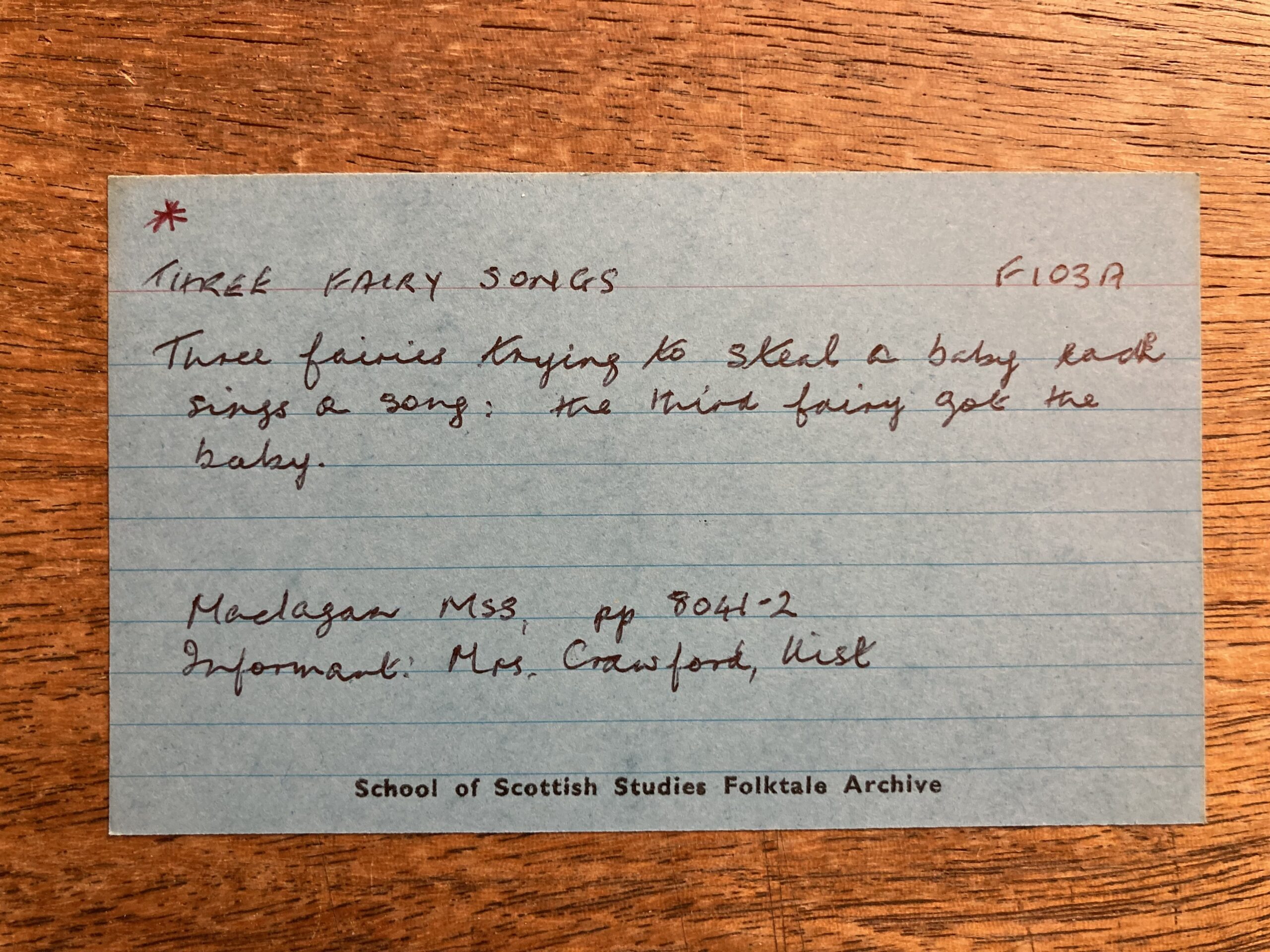

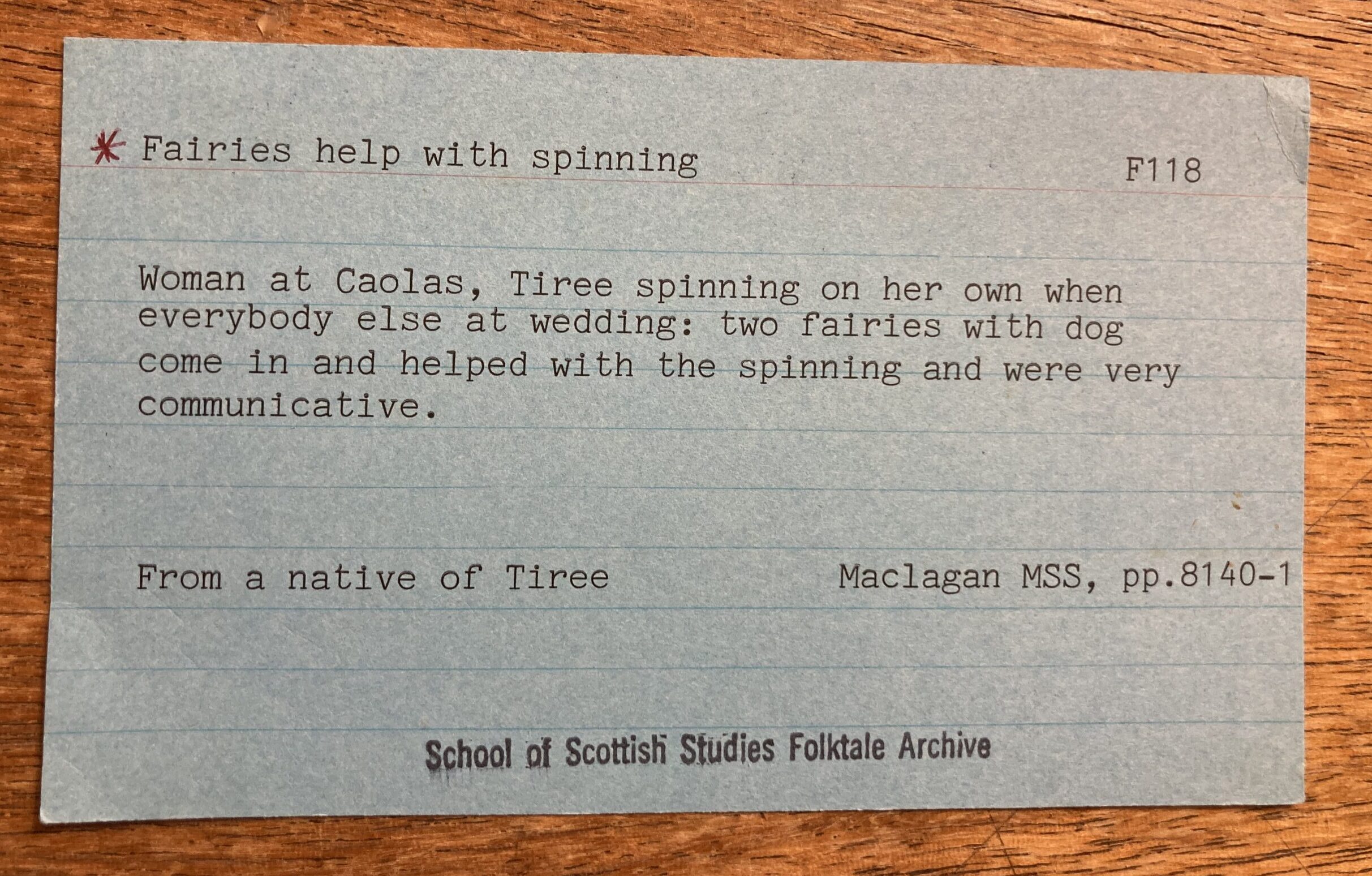

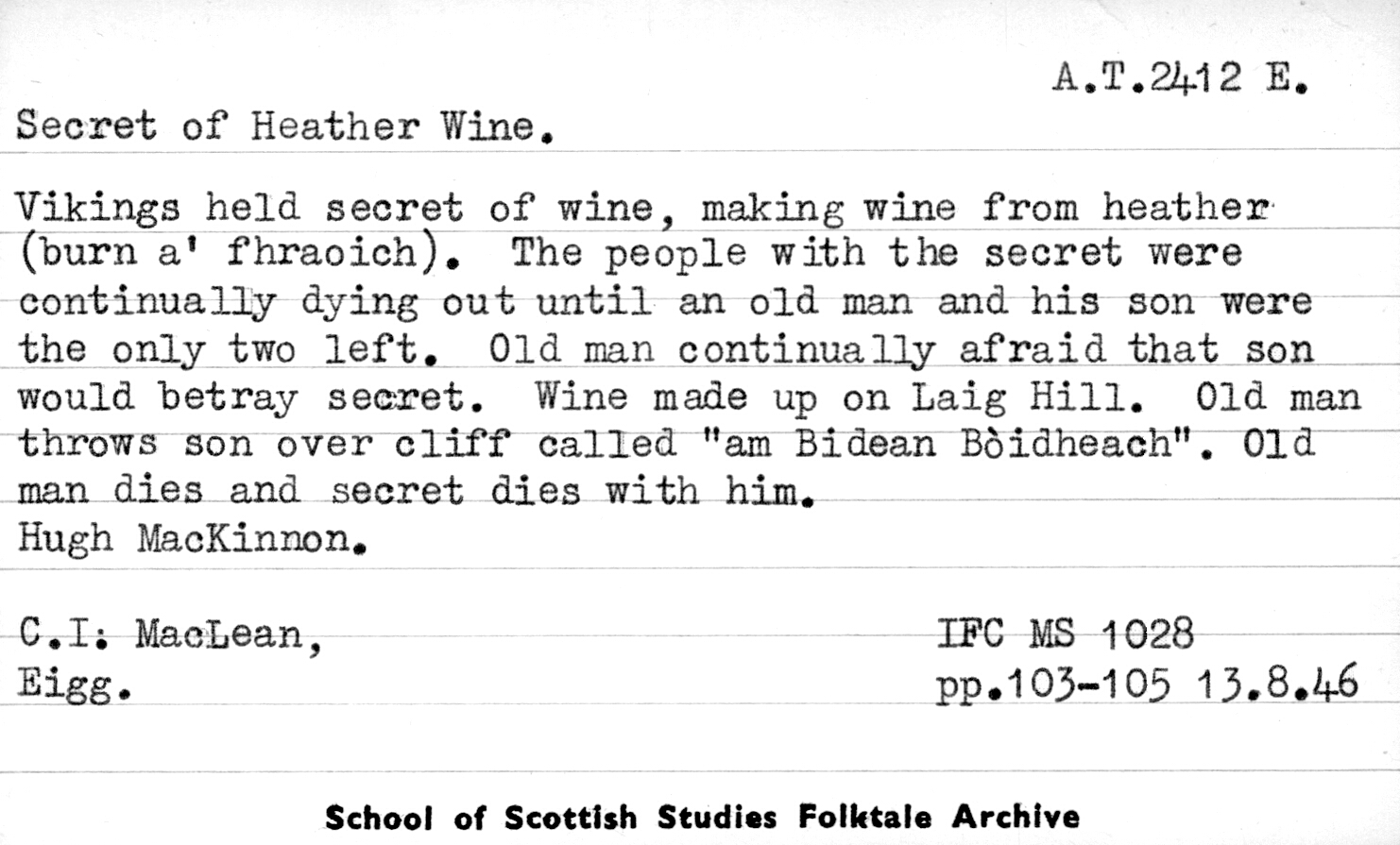

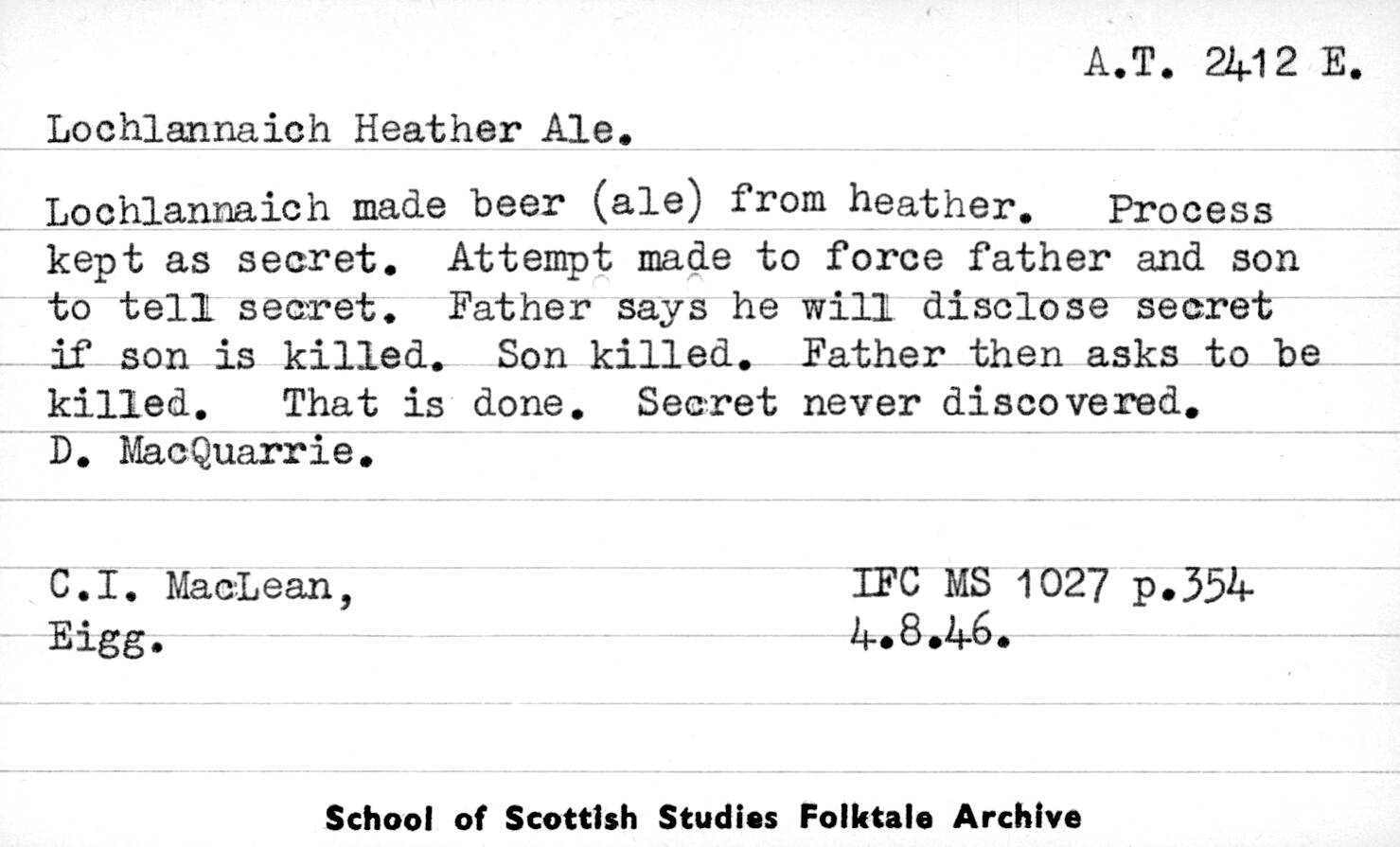

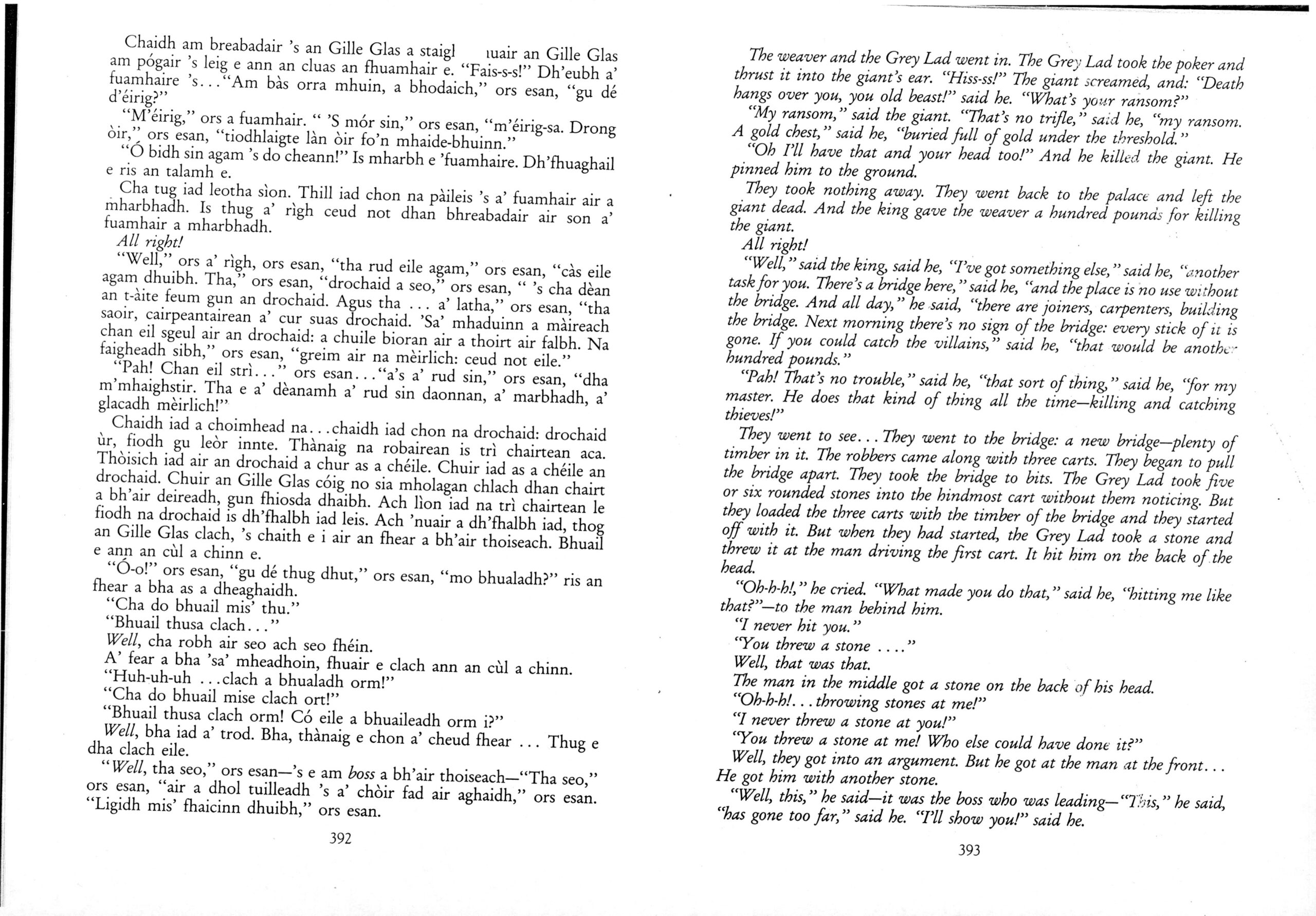

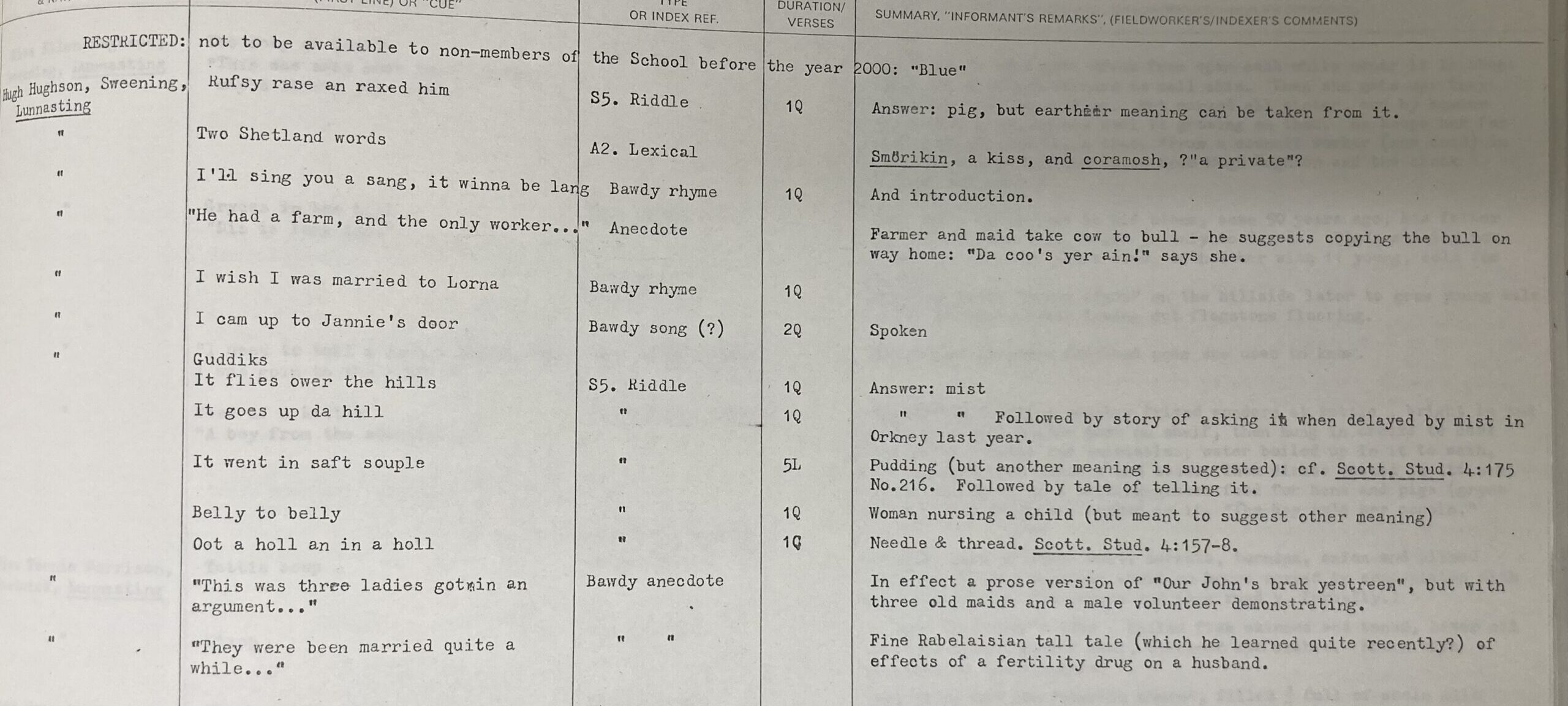

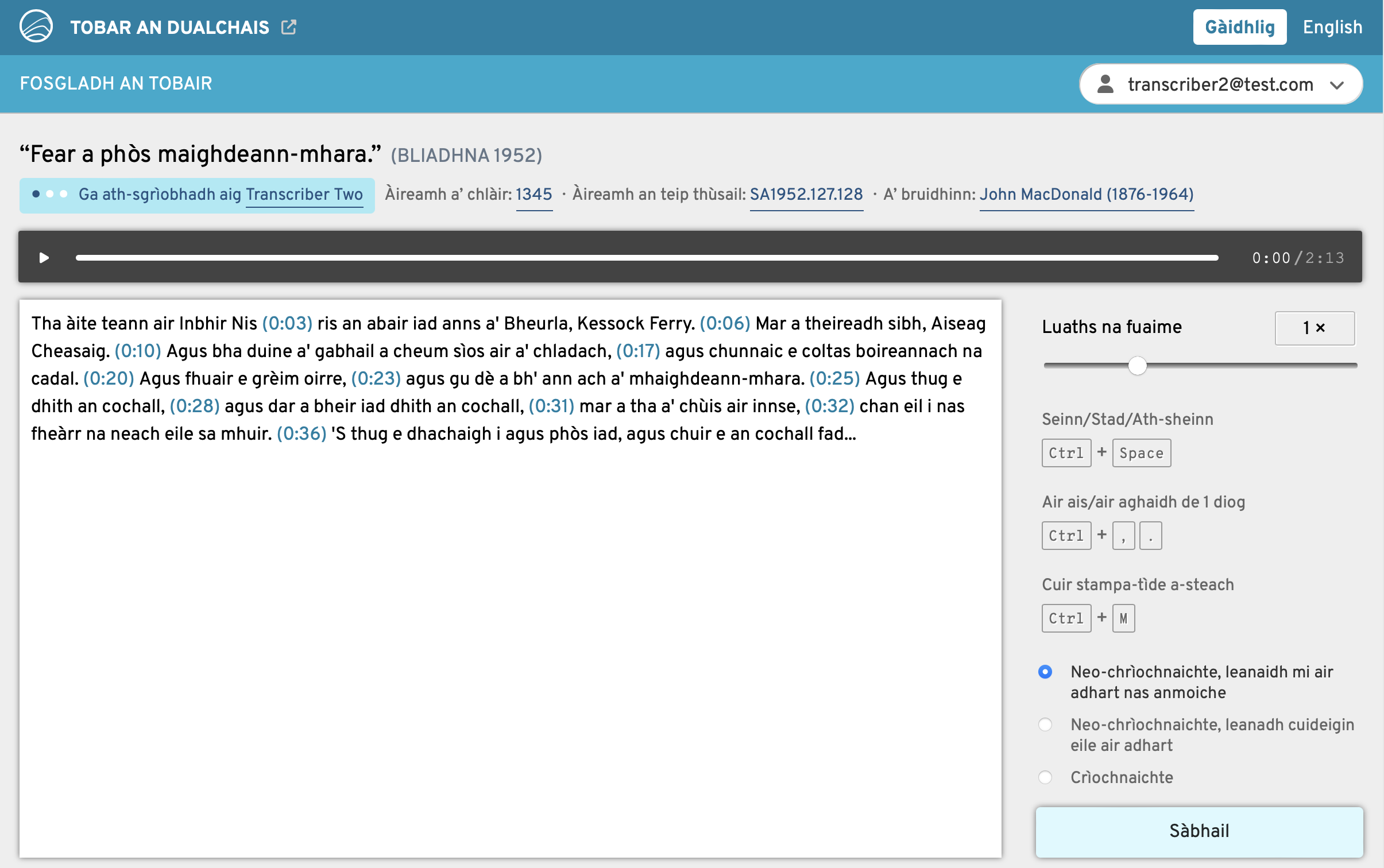

Central to ÈIST’s mission is Opening the Well, a pioneering crowdsourcing platform currently in development and due to launch in the last quarter of 2025. This initiative will mobilise the Gaelic-speaking community worldwide to transcribe audio recordings of traditional narratives and oral history held on the Tobar an Dualchais portal, such as those originally from the School of Scottish Studies Archives (University of Edinburgh). It takes its cue from Ireland’s successful Meitheal Dúchas crowdsourcing project. These transcriptions won’t just make Scottish heritage more accessible — they will also provide vital training data to enhance the accuracy and versatility of future speech recognition models.

The editing screen in Opening the Well

Risks, Rewards and Responsibility

The team behind ÈIST is keenly aware that speech and language technologies are not neutral tools. Poorly trained models can misrepresent language, distort culture or reinforce social bias. That is why ÈIST places community involvement at the heart of its design process.

The researchers also promote best practices for ethical AI use in revitalisation: curate transparent training data, return outputs to the community (e.g., through DASG, the Digital Archive of Scottish Gaelic), and avoid relying on ‘big tech’ to solve our problems, albeit poorly. It is a values-led approach as much as a technical one.

The Future of Gaelic in the Digital Age

Finally, ÈIST is developing an interactive, text-based interviewer chatbot. This promises not only to engage speakers in naturalistic conversation but also to generate essential data for future applications. When combined with speech technology, such a chatbot could assist with language learning, offering conversational practice previously difficult to achieve outside of a native-speaking community. While this will never replace human teachers, it could be a very useful adjunct to teaching and learning.

In a broader sense, ÈIST represents a powerful case study in how language technology can empower minority languages. The project’s blend of machine learning and cultural preservation illustrates how digital innovation can help to sustain diversity, rather than eroding it. For more information about ÈIST, contact w.lamb@ed.ac.uk

ÈIST Research Team

- Prof William Lamb (PI, University of Edinburgh)

- Dr Bea Alex (Co-I, University of Edinburgh)

- Prof Peter Bell (Co-I, University of Edinburgh)

- Ms Rachel Hosker (Co-I, University of Edinburgh)

- Prof Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh (Co-I, University of Glasgow)

- Dr Alison Diack (Transcriber, DASG, University of Glasgow):

- Mr Cailean Gordon (Lead transcriber, Tobar an Dualchais / Kist o Riches):

- Dr Ondřej Klejch (Speech processing specialist, Informatics, University of Edinburgh)

- Dr Michal Měchura (Web designer and computational linguist)

Links

- Prof Lamb’s inaugural lecture on AI and Scottish Gaelic

- Full demonstration video: Subtitles for BBC ALBA’s ‘An Là’

- A NotebookLM podcast unpicking the results from ÈIST’s new research paper (below)

- arXiv version of Klejch et al. 2025. ‘A Practitioner’s Guide to Building ASR Models for Low-Resource Languages: A Case Study on Scottish Gaelic’.