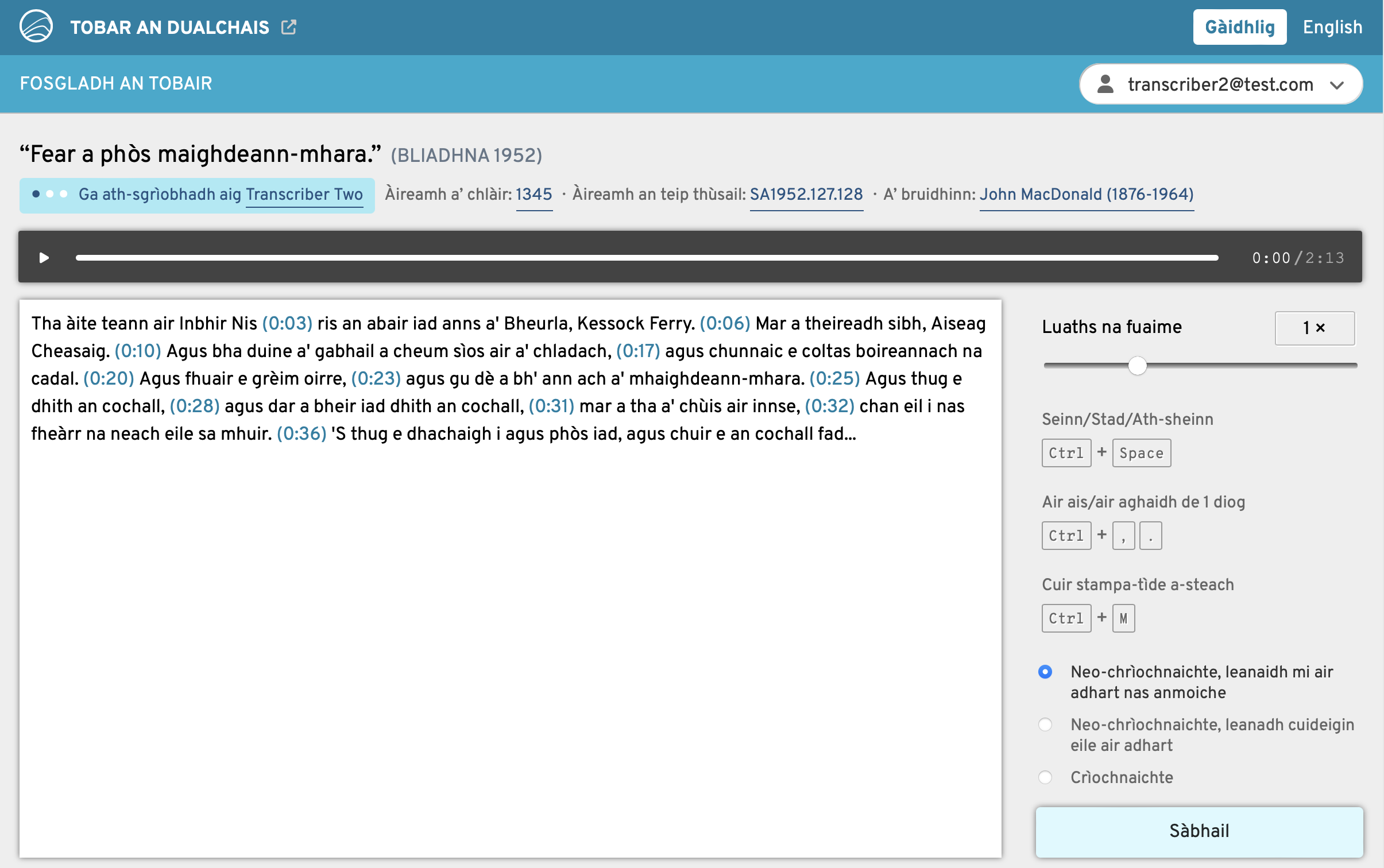

We are nearing a month of the Opening the Well website being live, and the number of transcribers on the platform keeps increasing which is so excellent to see – thank you to everyone who is taking part and has told others about it.

Image Description: The photo features a plush Highland Cow toy, sitting on a windowsill looking out an open window. Outside, there are green leafy trees and a multi-story grey building with a modern architectural design. Although not directly stated in the photograph, the image is being taken out of a attic room of 29 George Square, looking out to the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh in George Square.

There are also many folk interested in gaining transcriptions of Gaelic materials for a variety of reasons, research purposes, to family ties or artistic inspiration. We’re finding some of the connected projects and events you mention fascinating.

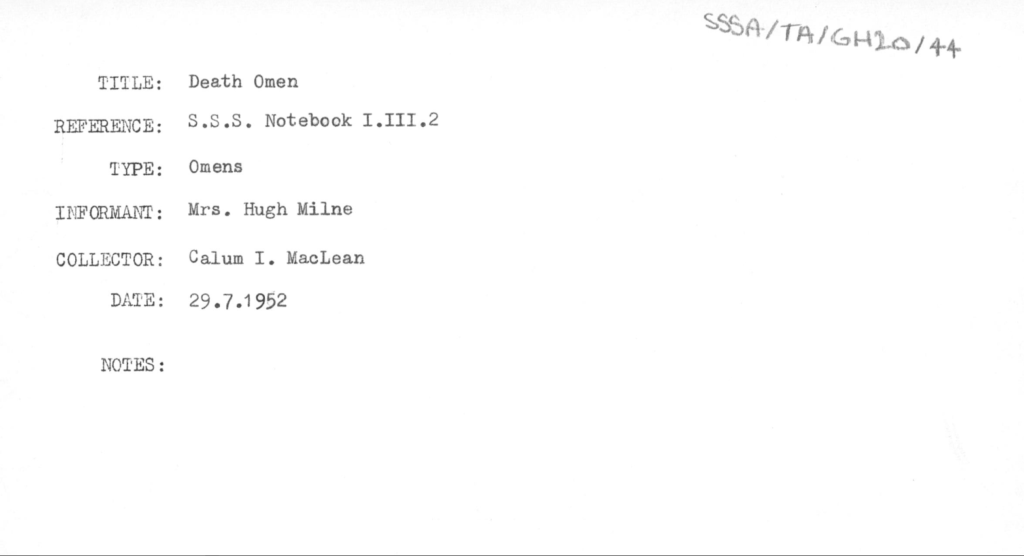

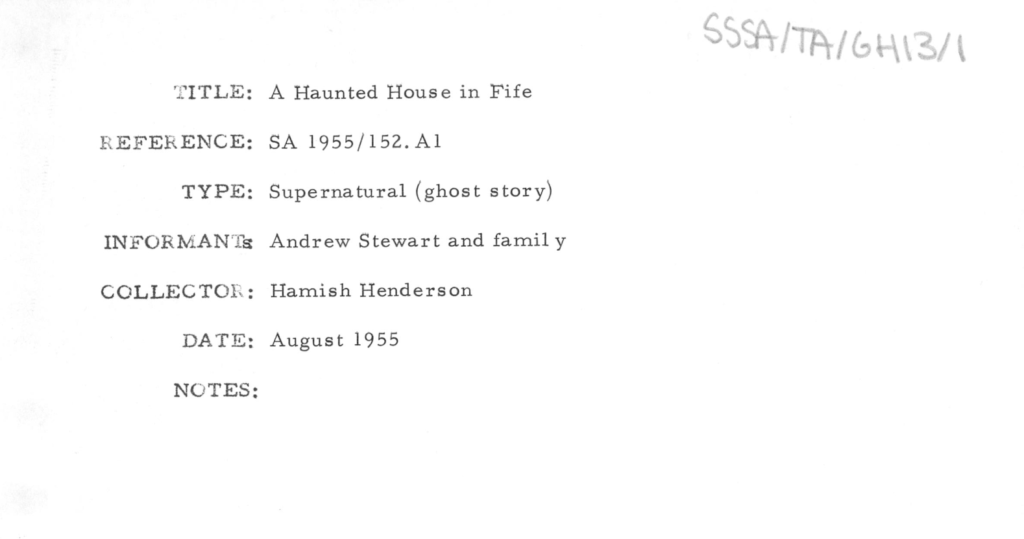

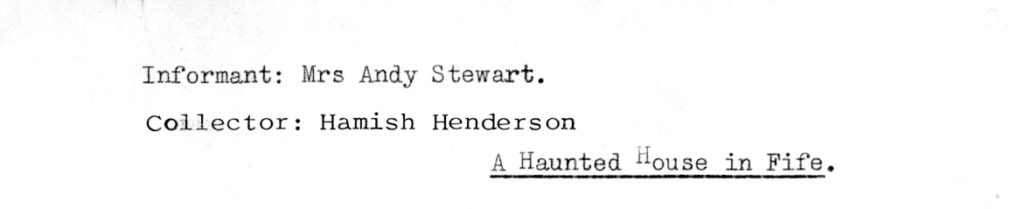

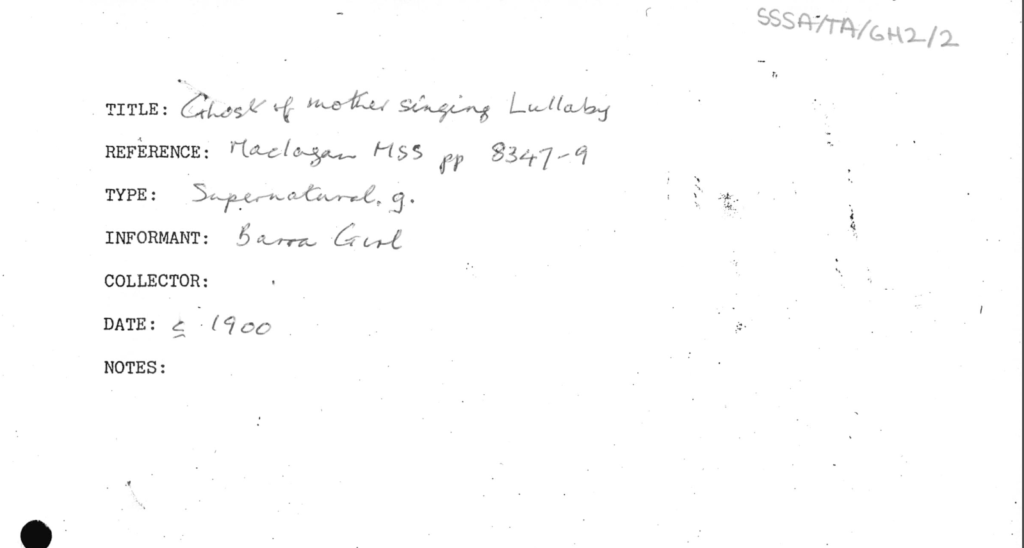

With new requests comes new permission checks, so here’s what Seumas – the Copyright & Permissions Administrator on the project – has been up to this December.

More tracks enter the Well

First up, was some harvest customs recorded on Jura. In 1953, Calum Maclean visited with Janet Shaw to learn about the traditions surrounding the last sheaf of a harvest and the festivities that would follow. You can listen to the track here.

Then, an item from South Uist got added to the list. We’re sticking with Calum Maclean as the fieldworker but it’s a later one for him – 1960 and with contributor Donald MacIntyre. He speaks about the knowledge and experience of the island midwife. Fifty years into her profession and she had the experience of being called upon by two families in labour at the same time. You can listen to Donald’s description of this here.

We were off to Harris next where Cait Dix was recorded by Ian Paterson in 1970. Cait has tonnes of tracks on Tobar an Dualchais and was a fantastic tradition bearer. On this particular tape, she talks about a girl taken by the fairies whilst out keeping an eye on cattle. She bakes scones for them, but has to work out how the amount of flour will ever diminish enough for her to go home. Listen here.

It was quite a heavy Calum Maclean couple of weeks in general, as the next two from Mull come from him. Both are back to the early years of the Archive coming from 1953. The first track is information based and talks about a piper playing a tune to warn a MacDonald that Campbells were coming. We link it here. The other tells the story of Murchadh Geàrr, who lost his lands and returned with men from the Earl of Antrim to take back the castle. It’s available here.

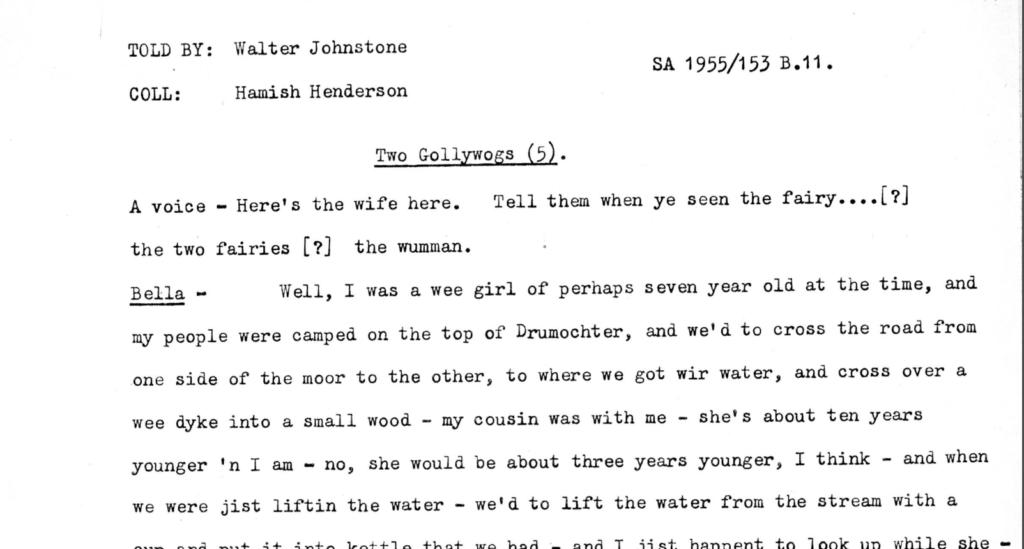

Overwhelmingly though, we’re sticking with a Barra theme for requests, similar to the launch tracks discussed in the last blog post. It was an excuse for Seumas to spend more time on the island.

Image Description: A circular stone mosaic set into the ground and surrounded by upright stone slabs. The mosaic is detailed with colorful, intricate patterns and symbols. It is designed to be a compass that features motifs of the island. On the side closest to the camera sits a stuffed animal toy. Around it is a grassy area with some rocks, leading towards a body of water in the background.

The next track is a group of folk, illustrating just how many people might need to be contacted for each track to be included in the Well. Hugh MacNeil, Mary Morrison and Annie MacNeil were recorded by Mary MacDonald and Emily Lyle in 1974. The conversation surrounds death omens. Listen here.

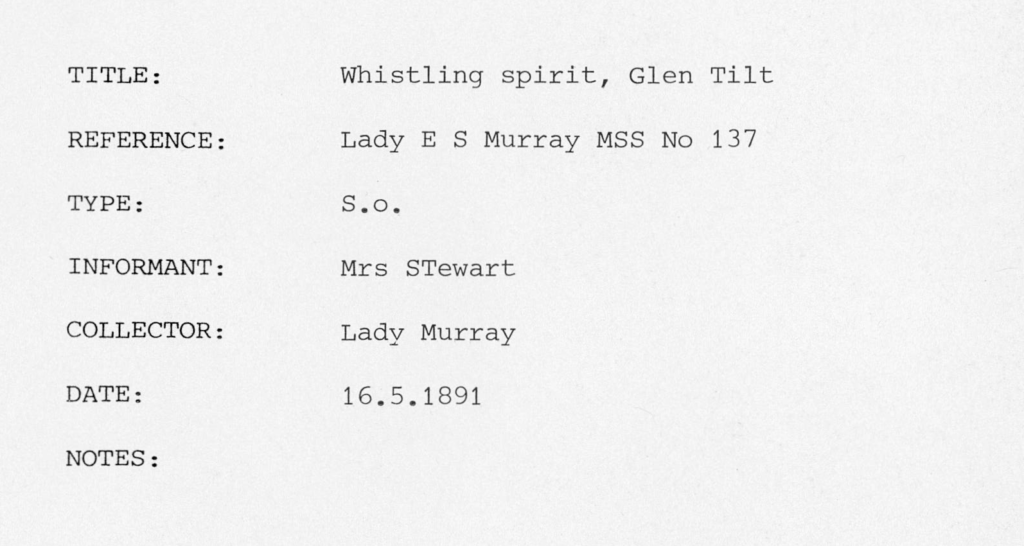

As we head into Castlebay, we have two tracks from contributor Neil Mackinnon. In the first track, Neil discusses a time he got lost in mist here.

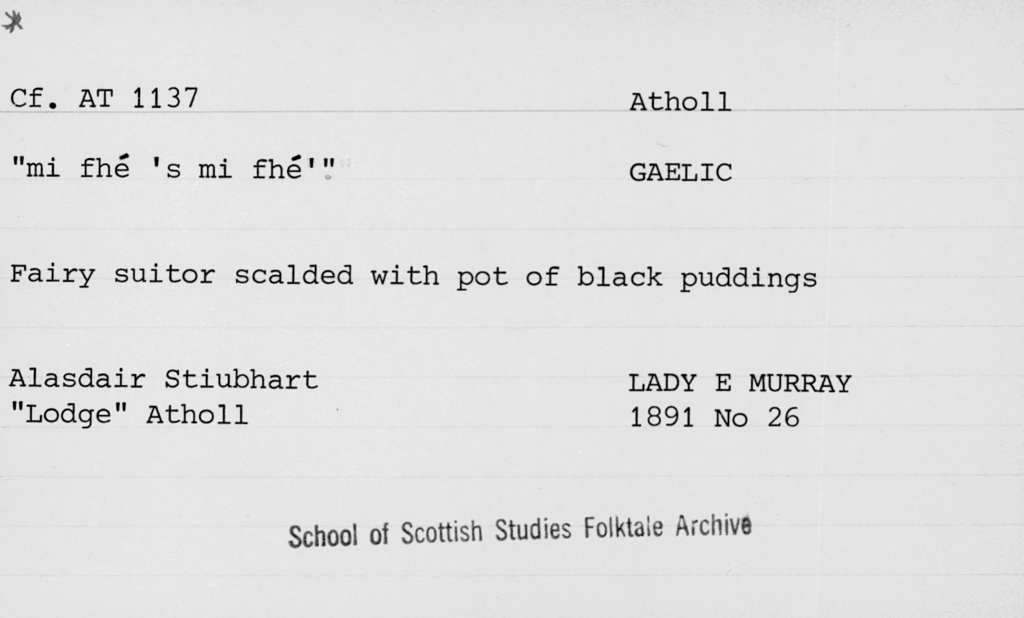

Image Description: A stuffed toy Highland Cow facing a road sign. The sign reads ‘Bàgh a Chaisteil, Castlebay,’ with a stone wall and a grassy area nearby. In the background, there is a modern car, some buildings, and rocky hills under a cloudy sky.

The second track from Neil discusses the SS Politician and stories of taking whisky from the ship wreckage off of Eriskay. This shipwreck is the reason that the pub there is named The Politician and the event inspired Compton Mackenzie to write Whisky Galore.

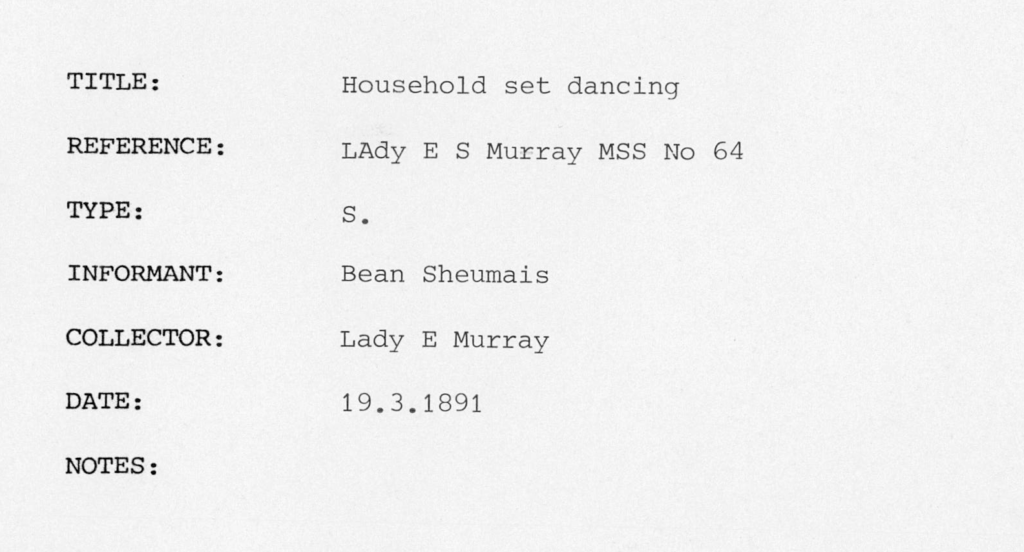

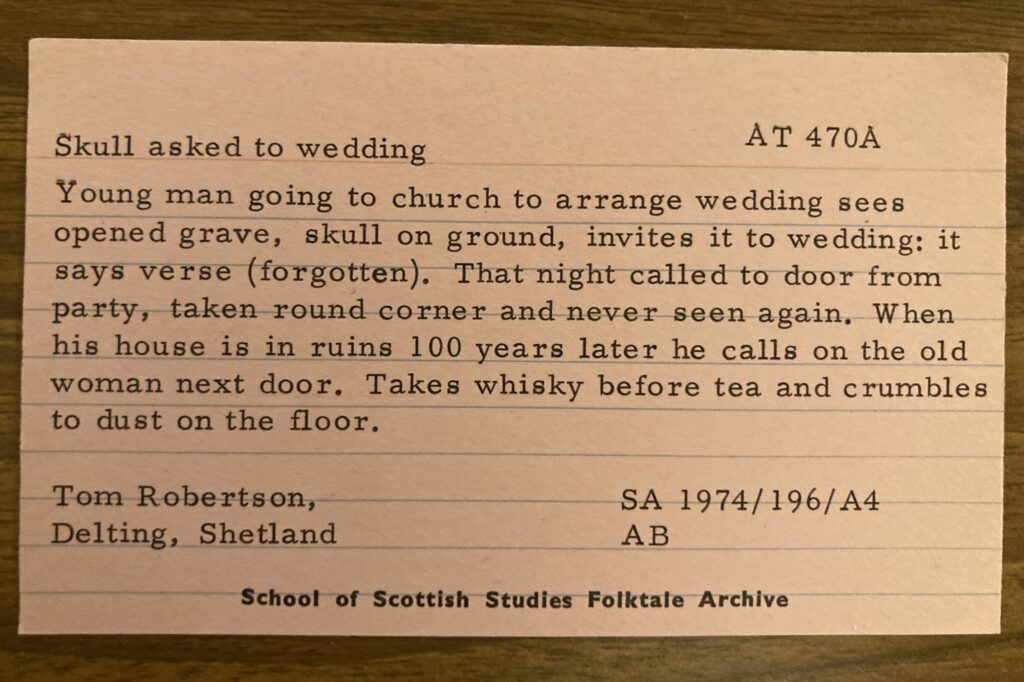

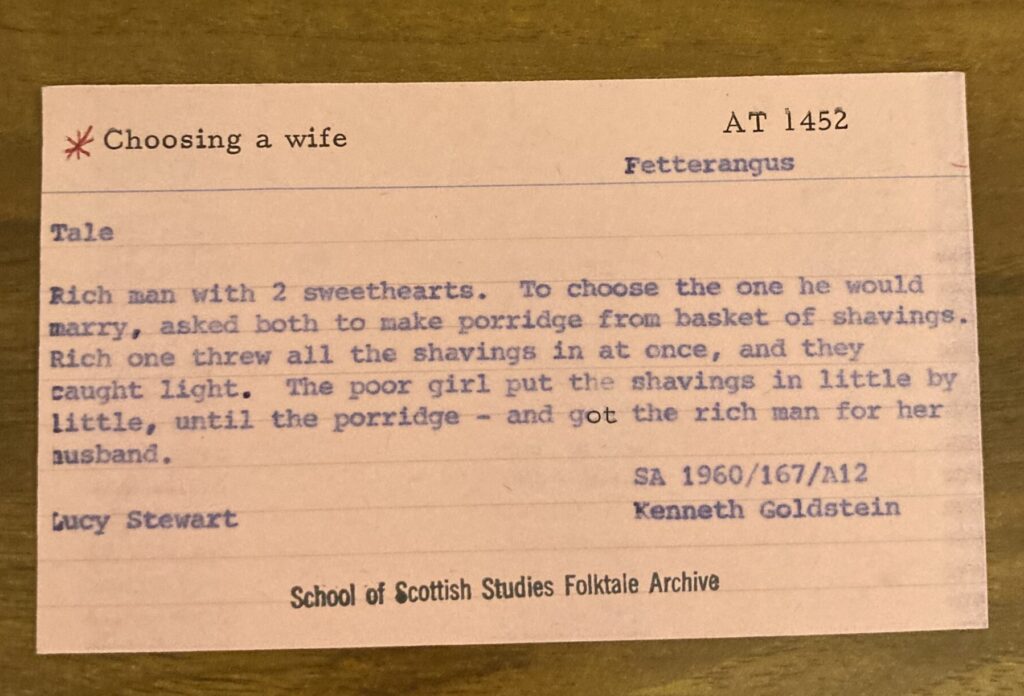

Seumas was able to visit Compton Mackenzie’s grave on his travels, seeing as the author was buried on Barra.

Image Description: The photo depicts a graveyard with several headstones and green grass. In the foreground of the photo, a plush toy resembling a brown cow or highland cattle with light-coloured horns and a tuft of orange hair is stuck up. The nearest gravestone, with a bunch of white, purple and yellow flowers laid infront of it reads ‘Compton Mackenzie 1883-1972’.

And with Seumas already in the Eoligarry area…

Image Description: A plush Highland cow is being held up in front of a countryside scene with green grassy fields and a cloudy sky. In the background, there is a white and black road sign that says ‘Eolaigearraidh’ with ‘Eoligarry’ written underneath, indicating the place name in Gaelic and its English equivalent. There is also a yellow sign on a metal gate further back, and a real Highland cow with horns can be seen standing in the grass behind the sign, blending in with the environment.

… another track becomes applicable. This one is from Rachel Mackinnon who speaks of a cauldron that was borrowed by the fairies’ multiple times. When they didn’t return it, the woman had to go to the fairy knoll to request it back. Find out how the story turns out here.

Heading in the opposite direction (island wise), we had a couple of Nan (Annie) Mackinnon tracks available in the launch, and unsurprisingly – as a firm favourite amongst the Archive/website users – she is back again already.

So, it’s a wee trip onto Vatersay whilst she speaks to James Ross about MacLean of Duart’s daughter and the black arts.

Image Description: A brown fluffy toy animal, a Highland cow, with white horns is placed in the foreground on the left side. In the background on the right, is a blue and green framed picture reading ‘Cafaidh Bhatarsaigh’ and shows a map outline with co-ordinates in silver lettering.

Listen to the track here.

So now you’re up to date on the tracks that we’ve been able to clear, usage wise, in the transcription project… and what better way to celebrate this fact on Barra than at Café Kisimul.

Image Description: The main photo features a small, stuffed plush toy of a Highland Cow with horns infront of a white building that has a colourful sign that says ‘Café Kisimul’. There is a second, smaller circular image in the bottom right-hand corner of an Indian meal with naan bread, curry and yellow rice on a table. It is taken inside the location of the main photo. There is a plate with a serving of rice and curry, a dish of curry with a spoon, and a large piece of naan on another plate. A plush toy resembling a brown Highland cow with horns is sitting near the food with a menu behind them.

Seumas will be back in the New Year with more updates regarding permissions. We hope you have a lovely festive break in the meantime (and maybe even spend some of that time transcribing).

Nollaig Chridheil agus Bliadhna Mhath Ùr (no Bliadhna Mhath Ùr, mas fheàrr leat sin!).

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

References

Cleachdaidhean aig àm an fhoghair ann an Diùra., Janet Shaw, Calum Maclean, SA1953.126.9, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

Iomradh air an eòlas a bh’ aig bean-ghlùine., Donald MacIntyre, Calum Maclean, SA1960.031.B3, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

Iomradh air diofar uairean a fhuair daoine manadh bàis., Hugh MacNeil; Mary Morrison & Annie MacNeil, Mary MacDonald & Emily Lyle, SA1974.92.A4a-c, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

Mar a fhuair Colla Ciotach rabhadh., Archibald MacLean, Calum Maclean, SA1953.105.B9, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

Murchadh Geàrr agus Oighreachd Loch Buidhe., Donald Morrison, Calum Maclean, SA1953.100.6, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

Na sìthichean agus an coire., Rachael Mackinnon, Mary MacDonald & Emily Lyle, SA1974.090.B5, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

Nighean a bha a’ fuine ann an sìthean ‘s mar a fhuair i às., Catherine Dix, Ian Paterson, SA1970.295.B3, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

Nighean MhicIllEathain Dhubhaird agus a’ bhuisneachd., Annie (Nan) Mackinnon, James Ross, SA1960.128.B20, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

The am fiosraiche ag innse mu uair a chaidh e air chall sa c…., Neil MacKinnon, Mary MacDonald & Emily Lyle, SA1974.90.B1; SA1974.90.B2, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh.

![Image shows metadata, a PDF and AI-recognised text for the Scottish Gaelic tale 'Biast na[n] Naoi Ceann' ['Beast of the Nine Heads']](https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/garg/wp-content/uploads/sites/1179/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-05-at-11.14.05.png)