One of the best things about having worked in The School of Scottish Studies Archives & Library for the past five years is seeing how people are connected with the archive recordings here.

I don’t only mean seeing how our readers are affected by connecting their own research to the myriad depths and layers of oral record testimony – though that process is rather like watching someone discovering treasure every single time. Once the Decoding Hidden Heritages project reaches its culmination, the transcript material from the Tale Archive will be another important layer to these recordings, and available for all to discover.

I also refer to the connections than extend outside the archives.

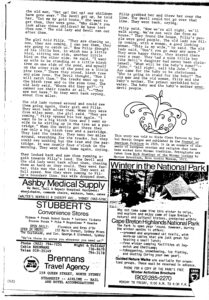

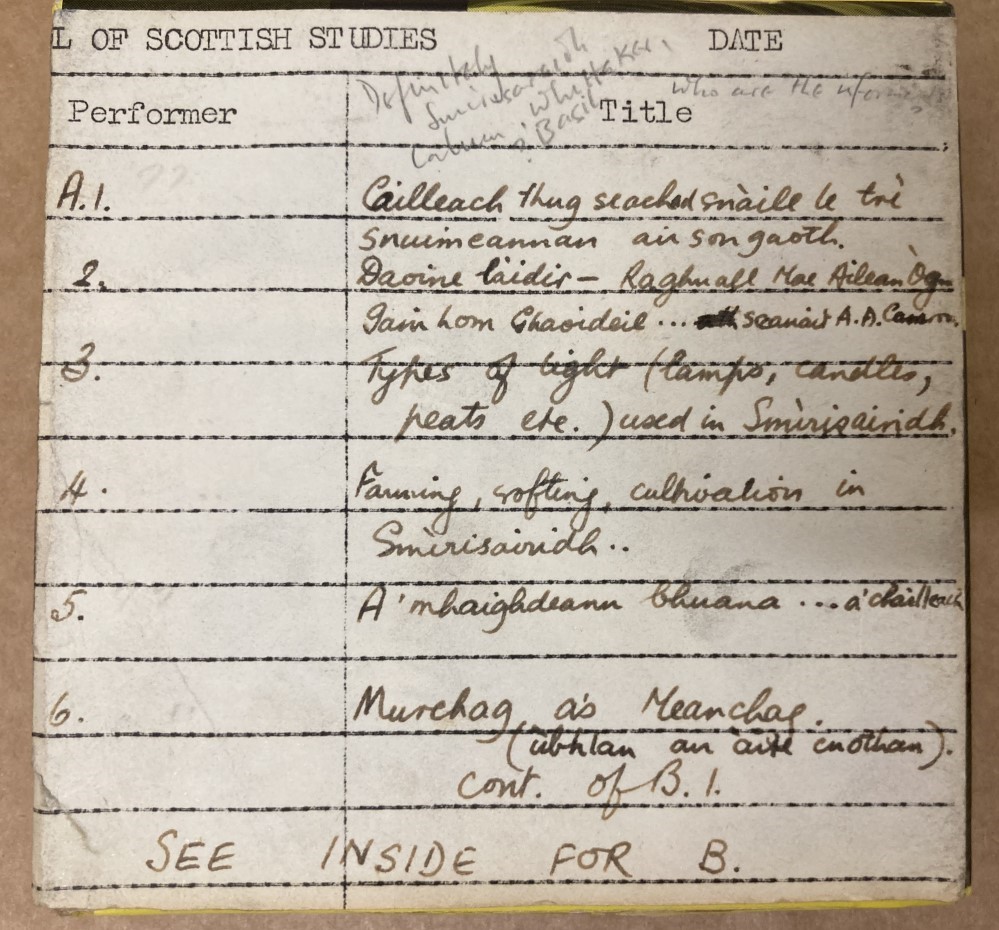

Angus MacNeil of Smirasary, Glenuig, being interviewed by Calum Maclean (out of image) 1959 Image copyright: SSSA

Many of the people who were recorded in the first decades of the School of Scottish Studies are no longer alive, but their material lives on in those who have connections to the people, their native area, or work or traditions. For example. Shetland fiddle players come to the collections to learn the playing style of the isles; Gaelic singers have used the archive to learn a regional variation of a song for performance; local heritage groups using material recorded in their location for museum exhibitions; storytellers learning tales…and the Carrying Stream flows on.

For me, these connections are particularly palpable when tied to family and we have great links with relations of some of our contributors and fieldworkers. Some can fill in details for us, such as other family members who were recorded or give background information that adds more depth. Often they give permission for re-use of material, if the archive do not hold the rights. Sometimes people come to us looking for recordings their relatives made and at other times we are connected with people who did not know their relation was recorded at all. In all of these instances those connections between contributor, recording, family and us, as the archive, are further strengthened and emboldened.

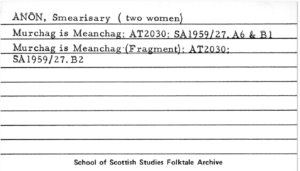

For those who read my previous blog on seeking the unknown person in the collections – I have an update! A former colleague (connections, again!) sent the post on to her friend from Glenuig who may have known my two unknown women of Smirasary – “You never know, he might have an idea who they are?”

Within a few hours I had a response – not only did he know who they were, but one of the women was his grandmother. The woman that was down in our records as “Anon Woman B / Mrs MacDonald?” was indeed a Mrs MacDonald. She was Johanna MacDonald (1880-1973) and there is more material in the Archives attributed to her from other fieldwork trips to Smirasary in the mid-late 1950s. You can hear some of those other recordings on Tobar an Dualchais. Another fantastic set of connections and one which will hopefully lead to these transcriptions becoming more accessible.

I never fail to be surprised at the connections people have to The School of Scottish Studies Archives, or the weight and strength of those connections!