Long read: Why the response to the climate crisis needs to be anti-racist

In our first long read blog, Ecological & Environmental Sciences student and Vice-President of the Sustainable Development Student Association, Emma Schoenmakers, explores why the response to the climate crisis needs to be anti-racist. Emma is passionate about climate justice advocacy, community-based conservation and volunteers with Amina Muslim Women Resource Centre in her spare time.

Many thanks to the many people who reviewed this piece and who were duly compensated, including Feiya Hu, from Racism Unmasked. Please note the views expressed here are the author’s perspective only.

After decades of work, it has finally been in the headlines for the past months: “anti-racism”. And while we should all aim to be “anti-racist”, do we really understand what it means, the responsibility it carries and the force for good it has the potential to become?

Before I go on about why we need an anti-racist response to the climate crisis, I would like to clarify that I am nowhere near the only representative of this movement. So much of the knowledge I have gained throughout the years comes from academics, activists – especially Black activists, scientists and knowledge passed down by my family’s lived experiences. As a consequence, a big part of this piece will come from my perspective and give examples of how the Black community is affected by environmental racism. This does not, however, ignore that East and South East Asian communities for example, are at the crossroad of increased Covid-19 related hate crimes and the climate crisis and have to be included in anti-racism conversations to achieve an equitable response to climate change.

Why do we call it a climate crisis in the first place?

The barriers to participation in environmental movements are a consequence of the inaccessibility of spaces due to lack of diversity, access for disabled people, digital and knowledge access, jargon,… The latter should never make you feel like you do not deserve to advocate for what you believe is right and/or what you may have experienced. Allow me to put my ecologist cap on first to delve into the meaning of the term climate crisis.

The difference between weather and climate is a timeframe. Weather refers to a short-term measure of conditions in the atmosphere i.e. it is going to rain today while climate refers to long-term averages of weather trends over 30 years i.e. in March in Edinburgh, the rainfall averages 51.7mm and the city has a temperate maritime climate. Climate change is when these patterns shift, with extreme weather events becoming more severe and frequent. For example, we will see warmer winters and more floodings if you take the U.K.’s perspective.

So when we say your climate advocacy should include those most affected by the climate crisis, we not only mean often-targeted communities near toxic facilities, we also mean darker-skinned women, disabled individuals, LBGTQIA+ individuals and those often at the crossroads of all these identities.

The politics of climate terms

Climate change is a term used by the scientific community and democratised beyond. The term climate change has been used by many companies, particularly oil and gas companies, to tone down the urgency of the situation in which they have played a big role in, due to its arguably distant connotation and the passive role it gives us. The term climate crisis, however, is a more recent term adopted by politicians, international bodies (like the United Nations) but also activists, community workers and more to tell it like it is: we have to drastically cut our emissions to minimise catastrophe in the next decades. It attempts to create a sense of urgency that reflects what it means for everyday families, single parents, students or vulnerable communities. The climate crisis is something we can all act on.

Now we have acknowledged that the climate crisis is also a people issue. It is equally important to underline that we, as humans, are part of nature, not separate. This might sound like something someone in academia might say and there has indeed been a lot of academic research on this aspect. Essentially, we need to reframe how we perceive our planet as not one where we are its center but where we are connected and dependent on all the natural things around us. It’s not just about our own existence anymore. What stems from this connectivity are also important values of empathy and compassion and I invite you to apply this in your everyday lives but also in the following lines you are about to read.

Environmental racism

In Afiesere, in the Warri North district of the Niger Delta, local Urhobo people bake tapioca in the heat of a gas flare. © Ed Kashi/2004

The term emerged in the USA in the 1960s during the American Civil Rights movement and was later coined by Dr Benjamin Chavis, an Afro-American civil rights activist, after noticing the intentional and unintentional targeting of BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic) for the location of toxic waste sites on top of exclusion from environmental policymaking. This is still happening today in the USA such as in the often mentioned Flint water crisis, but also in Nigeria with Shell’s oil extraction in the Niger delta, or in the UK where BAME groups in England are exposed to 12-29% higher air pollution levels (PM10 concentration) than of White British.

You might think these examples are one-off occurrences, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. Racism itself can be broken down in different categories: Structural, internalised, interpersonal and institutional.

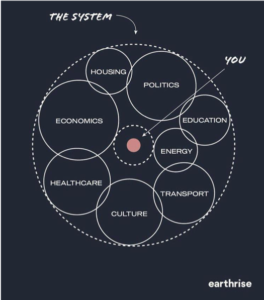

Credit: Earthrise

Structural racism is also used interchangeably with systemic racism. A system is an interconnected network of parts making up a whole. Put into context, multiple institutions, say healthcare or the banking system may be upholding racist policies in practice. With regards to the climate crisis, this is exemplified in the historical lack of land ownership by Black people or the delay or denial of farm loans in the US.

Internalised racism is a result of subtle and apparent messages that reinforce negative beliefs and self-hatred in individuals. For example, the fact that the environmental sector, save farming, is the least diverse sector in the UK with only 3.1% professionals from BAME backgrounds. With that in mind, BAME children or students will be less likely to enter this field because we simply don’t feel like we belong. We need to have a seat at the table, a voice that is listened to and acted upon since we will be the most affected by the climate crisis in the first place. And no, internalised racism is not due to low self-esteem, it is a consequence of a system that “actively discourages and undermines the power of communities of colour” and gets us stuck in our own position.

Credit: Slow Factory Foundation

Interpersonal racism stems from microaggressions and racist acts carried from one person to another. This can range from hiring discrimination to denial of racism or exclusionary curriculums. I believe these are all quite self-explanatory.

Lastly, institutionalised racism is defined as the way in which policies and practices within an organisation or workspace prevent people of color from accessing the opportunities in society. This can be seen in exploitative labor and the fact that, for example, Bangladeshi employees in the U.K., earned 20.2% less on average than White British employees.

Colourism

*Trigger warning: mention of sexual violence*

An article about anti-racism will never be complete without touching on the topic of colourism. The term colourism was pinpointed by writer and activist Alice Walker but has roots in the USA and slavery where oftentimes slave owners raped enslaved black women and their lighter-skinned children were then given preferential treatment compared to their darker-skinned counterparts on plantations, owing to their affiliation and skin tone.

European colonialism has also left its mark in Asia like the Philippines whereby skin tone was often linked to class. Essentially, if you were darker you worked a lot outside and were part of the working class while the people closer to a white skin tone were assimilated to the elite and European ruling class at the time. A lot of people of colour will have heard this, but this is seen throughout the world where your parents tell you to “avoid the sun otherwise you will get dark”. In other cases, you will be advised to buy lighting cream to enhance employability, which may have detrimental health effects as they often contain mercury.

Being mixed-race of Malagasy and white descent, I am directly benefiting from the consequences of colorism. It is both an issue within our own communities and between communities. So next time you are looking at the news or promoting someone, maybe have a think about whether colorism has affected your judgement (and this of course applies to me). When applying this to the often-mentioned idea of representation, ask yourself whether you are only platforming light skin individuals because they are as close as possible to whiteness.

The reality is that dark-skinned individuals are less likely to be preferred in hiring instances, heard and represented higher up in companies. So when we say your climate advocacy should include those most affected by the climate crisis, we not only mean often-targeted communities near toxic facilities, we also mean darker-skinned women, disabled individuals, LBGTQIA+ individuals and those often at the crossroads of all these identities.

Anti-racism

Ibram X. Kendi. (Philip Keith for TIME)

Anti-racism theory has stemmed from decades of work by French, British, African-American scholars and much more. It is important to remind ourselves that Black voices throughout the globe have been silenced, purposefully cast aside, and oftentimes violently so, for centuries. Anti-racism has existed for centuries just as colonialism, slavery and race-related violence has existed for centuries. This term is not a new fad to add to your dictionary.

Anti-racism is about lives.

The first people to have coined it is believed to be W.E.B DuBois, an Afro-American Civil Rights activist, along with his ‘literary executor’ Herbert Aptheker in the early 1940s. Later on, in his book “How to be an Anti-Racist”, Ibram X. Kendi, founding director of Boston University’s anti-racist research centre and New York Times bestselling author, cemented the term in the 21st century.

Anti-racism leaves no room for neutrality. You are either racist or actively working against racism. In that work, the importance of including all marginalised ethnic groups in the many layers of anti-racism work cannot be stressed enough. To paraphrase Kendi, we have to consistently identify racism, pinpoint it and dismantle it. This also applies to yourself through “persistent self-awareness, constant self-criticism and regular self-examination”.

To quote writer Ijeoma Oluo:

“The beauty of anti-racism is that you don’t have to pretend to be free of racism to be anti-racist. Anti-racism is the commitment to fight racism wherever you find it, including in yourself”.

As we have seen that racism is not only occurring in apparent, blatant acts of racism but also through multiple layers and forms of more or less subtle occurrences, we must be critical in examining how they are embedded in our everyday lives. Racism itself, however, was historically created by white people and the work should therefore fall on white people to dismantle policies, everyday actions and systems that continue racism to be pervasive in our society today. Although it was not created by white people today, white people continue to benefit today. Therefore, to be anti-racist, we need to acknowledge these issues and move past guilt and instead work towards tangible action that promotes the safety and growth of people of colour. Moving forward, in the same way that white people should use their position to advocate and promote the voices of BAME people, lighter-skinned people of colour and those who pass as white should use their position to advocate for, but not speak over, darker-skinned people of colour.

So, in practice how does this apply to the climate crisis?

Because being anti-racist means you are fighting against systems of oppression, many of the systems that contribute to the climate crisis also contribute to racist policies or subtle occurrences of racism.

When considering healthcare for example, why is it that the medical curriculum approaches white bodies as the norm thus negating how different skin tones present different diseases? Building on that, why is it that Black British are 4 times as likely to die from Covid-19? Part of the answer lies in discrimination in healthcare access, another part also lies in the fact that 15% of Black African households live in overcrowded housing, are more likely to be subject to environmental pollution, damp and mouldy flats and be more vulnerable to Covid-19 due to chronic respiratory diseases.

Taking a step back, ask yourself why it is that the majority of our pollution has been exported to countries in East and South East Asia in the first place? Or why is it that the fuel for our cars is drilled in countries like Nigeria which has led to decades of local water poisoning?

A river canal in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Photo: Sen Nguyen

The effects of the climate crisis are being felt today in the countries that have contributed least to it, on the African continent in South America or Asia. These are the countries that experience longer periods of droughts, increased loss of biodiversity, more frequent storms and now today are more vulnerable to the emergence of zoonotic diseases like Covid-19.

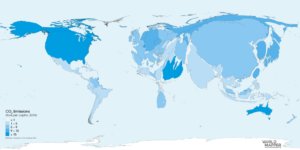

Being just when dealing with the climate crisis is also important to determine where action is to be taken. Despite the fact that ⅔ of the greenhouse gas emissions originate from 10 countries like the USA, Canada, China or India, it is worth reminding ourselves that China has been the ‘world’s factory’ for the past few decades and in 2018 accounted for 28.4% of the world’s manufacturing power. On top of that, there has to be a shift in responsibility and the role that over-consumerism plays on the environment. Canada and the USA for example have the highest per capita (per person) greenhouse gas emissions ranging from 18-22 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) while India emits 2.3 tCO2 per capita and China sits at 7.38 tCO2 per capita, roughly three times less than the USA in 2016.

Map of carbon dioxide emissions in tons per capita in 2016. Countries in dark blue have the highest emissions per capita.

Beyond an individual level, notions of justice also apply to how implementable uniform environmental standards can be and how they should take into account the linked social and economic costs for ‘developing’ countries. This has been written in the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Rio as the “Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR)” principle and does not absolve countries from responsibility. For example, major strides have been made by countries like China, world leader in renewable energy production, and has the power to raise living standards in a, relatively, clean way. Justice is achieved not only in shifting the responsibility away from individuals, or worse, the average number of children per woman in the Global South, but instead to countries in Europe or North America, corporations, systems and the people who have designed those institutions.

What can I do?

Educate yourself, be self-aware but also be mindful of raising discussions with BAME people around you. You are talking about trauma they and their families have been going through for generations, maybe unwearyingly. In contrast to what may be implied by the controversial term ‘BAME’, people of colour grapple with racism in different ways and it is also up to all of us to challenge internalized racism and biases and interrupting patterns of prejudice against other racial groups.

Anti-racism is about taking action

The keyword in the definition of anti-racist is being proactive. This means that you have to dedicate some time, effort and money to promote an anti-racist approach to the climate crisis. In practice, this means showcasing the voices of underrepresented people of colour in the climate debate, those who have been fighting with their lives on the frontlines such as indigenous peoples protecting the Amazon, local people in Uganda fighting against deforestation, Filipino activists fighting against destructive mining but also those living in predominantly working-class suburbs in Glasgow.

It is however not enough to listen; action also means fighting racism in the institutions we are participating in. Anti-racist action means doing what makes us the most uncomfortable and not counting on climate leaders or 14-year-olds to do it for us. Dependency on that one individual or younger generations is fragile and unsustainable, and we must take it upon ourselves to enact change today.

This is not about yourself or your status either. Tough conversations and actions need to be encouraged first and foremost to fight prejudice in all the places we participate in. Attainment gaps, employability or salary differences are still occurring in the environmental sector. Financial opportunities need to be promoted to actively bridge these gaps which have increased during the pandemic.

I wish I could see more scholarships for BAME students in environmental science so I don’t have to walk in a room where all my professors are white and there are only 10% BAME students. I wish unpaid internships were not as prominent in the environmental sector when this put working class and BAME students at a disadvantage even before they have graduated. Questioning and changing who has designed those systems, who it favours and how it shapes the world, is what we can all do to strive to always be and do better.

Making the environmental movement equitable and anti-racist will not only mean preserving the lives of marginalised communities and threatened ecosystems but it will better equip us with a variety of tools and experiences to build a more resilient society today.

Actions to take:

Examples of anti-racist climate action may look like this:

Individual action such as listening to interviews, watching documentaries of people working in climate and social justice, those on the frontlines of climate action in the Global South or from marginalised communities in your local area. Anti-racism is also about being self-aware. Be vulnerable enough to accept that you may have, for example, internalised racist discourses. This will feel uncomfortable, but it only means that this is the right step forward.

Equally, not everyone has the time or ability to become an activist, yet we all have a role to play when we tap into our strengths and passions. For example, you can have an advocacy role by being a climate researcher, poet, lawyer, community leader. You can also directly empower individuals to take action as a teacher, social worker, parent. You can also create disruption by leading protests on the ground or through social media campaigns. It is the diversity of people’s backgrounds that will make climate justice embedded into every aspect of society.

With your friends, family or co-workers by initiating important conversations centred on the lived experiences of people of colour in relation to the climate crisis. Be aware of prejudice and racism and how it is present in your conversations and discourses. Not engaging with people because they have unconscious biases or racist discourses only means that the rest of the work to educate these people will fall on BAME individuals. To quote Marie Beecham “your goal isn’t to fight people, it’s to help people fight prejudice”.

Within your local area and/or at a national level, support/take part in groups that are driving positive changes and discussions on climate action but also social justice. Here are a few examples of (mostly) UK-based organisations and resources:

- Pass the Mic

- Climate in Colour

- Black Geographers

- Intersectional Environmentalist

- Hot Take Podcast & Newsletter

- Yikes Podcast

- SCOREscotland

- Amina MWRC

- Scottish Refugee Council

- One Parent Families

At an institutional level, by actively centering an anti-racist climate approach in the systems you partake in. This could be by engaging with marginalised communities that are not typically represented in the discussions you are having. Moving beyond simple representation, giving marginalised communities the platforms and opportunities to speak for themselves and drive change is as important. Nonetheless, the burden should not systematically fall on them to educate you or come up with your EDI (Equality, Diversity, Inclusion) strategy while the rest of the key actors stay complacent. This is also a reminder that if you are seeking out perspectives from marginalised communities, they should be financially compensated (as has been done for this article).

One last thing that I would like to stress is that you will make mistakes, I know I have. So be kind to yourself. As long as you are respectful, take ownership of your actions, and are committed to learning and acting for change, the only way is up!

Note:

This post is lacking in giving personal experiences of darker-skinned women in Europe, individuals living in the Global South who are today suffering from the majority of our emissions in the Global North, which I hope will be tackled by this series of articles. There is equally much research on the links between racism and capitalism or the links between the prison system and racism and many more topics that I hope will be tackled within this university bubble but more importantly beyond our own comfortable spheres.

Recent comments