Engaged Online Teaching and Time Management

Because technology is often associated with flexibility and fast time, this can lead to assumptions that online learning is faster and better. Institutions need to provide education in ways that fit with the lives of individual learners, and that means restructuring teaching time in flexible and personalised ways. A key part of engaged online teaching is mitigating transactional distance by planning for how teaching can be structured in both synchronous and asynchronous ways.

Redefining Contact Time

Contact time generally refers to the tutor-mediated time allocated to teaching or providing guidance and feedback to students. There has to be a different way to define contact time online, taking into account student mobility, distance education and flexible patterns of study. Online contact time can be characterised by personalised tutor presence and input within a specified time-frame.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Activities

There is some evidence that synchronous teaching is connected with improved learning outcomes. This is probably due to its ability to mitigate transactional distance, foster engaged learning communities, develop teaching relationships and demonstrate engaged teaching.

Some examples of synchronous teaching activities:

- an online tutoring session

- a design workshop

- an open discussion on a particularly challenging reading or concept

- a feedback session around student work

- a review of common issues with a particular assignment

- open office hours

Here are some tools that can be used for synchronous contact time:

- Skype

- Zoom

- Teams

- Blackboard Collaborate

Considerations for Synchronous Activities

- How long? Generally an hour session is long enough

- Video, audio, or text only? Different tools will offer different features

- Your student demographic, for example, video is bandwidth intensive so it may be difficult for some to participate.

- Your students’ time zones: morning UK time will exclude those in large parts of the Americas, whereas late in the day UK time eliminates most of East Asia and Oceania.

Remember, that these [synchronous] sessions can potentially have positive impact on both learning outcomes and the mitigation of transactional distance. They help establish teacher presence and help make engaged learning communities around that presence. Use them.

Here are some tools that can be used for asynchronous contact time:

- moderated discussion forums

- blogs

- wikis

- Padlet

- Thinglink

(I don’t think I’ve seen Thinglink yet!)

How much time does online teaching take?

Online teachers need to adapt to students’ time flexibility. They do not have to be online and responsive at all times, but they need to consider what would create an improved student experience and what would be good teaching practice in their field. It is necessary to provide a sustained and responsive teaching presence, but not an omnipresent one. It is up to the individual teacher to calibrate the amount of contact time required, however, they need to be creating a teaching presence where engaged teaching takes place, and students will still have expectations as to what contact time means.

Setting Expectations

Setting expectations about contact time is crucial. This can be organised by block off time in a calendar for synchronous teaching sessions, responding to forum posts, weekly summaries, responding to non-urgent questions, and other forms of teaching contact. These expectations can then be clearly stated in course descriptors or weekly summaries.

What about the students’ time online?

Considering the definition of “nearness” to a distance programme as a temporary assemblage of people, circumstances, and technologies, it is difficult to sustain this consistently when the typical online student may be studying part time over long periods, interrupting and resuming their studies from time to time.

Time online will ebb and flow over the duration of the course and the programme. Online students tend to skew a bit older, a bit more professionally-oriented than those on the traditional campus. They will have be preoccupied from time to time. We shouldn’t inherently equate time online with an achieved learning outcome. It could be something else: a sick child, a particularly difficult week of work. You can encourage students to let you know when life gets in the way and impacts their engagement. It is a form of time management in and of itself. Time online and performance might positively correlate for some; for others, it won’t. Noticing the difference is very difficult without an engaged teaching presence.

– An Edinburgh Model for Online Teaching

Links and References

Near Future Teaching (2019). Final Report.

Ross, J.; Gallagher, M.; Macleod, H. (2013). Making distance visible: assembling nearness in an online distance learning programme. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Education (IRRODL), 14(4).

Selwyn, N. (2011). ‘Finding an appropriate fit for me’: examining the (in) flexibilities of international distance learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 30(3), 367-383.

Sheail, P. (2018). Temporal flexibility in the digital university: full-time, part-time, flexitime. Distance Education, 39(4), 462-479

Watts, L. (2016). Synchronous and asynchronous communication in distance learning: A review of the literature. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 17(1), 23.

Time Management for Online Learning. KPU Pressbooks: Learning to Learn Online.

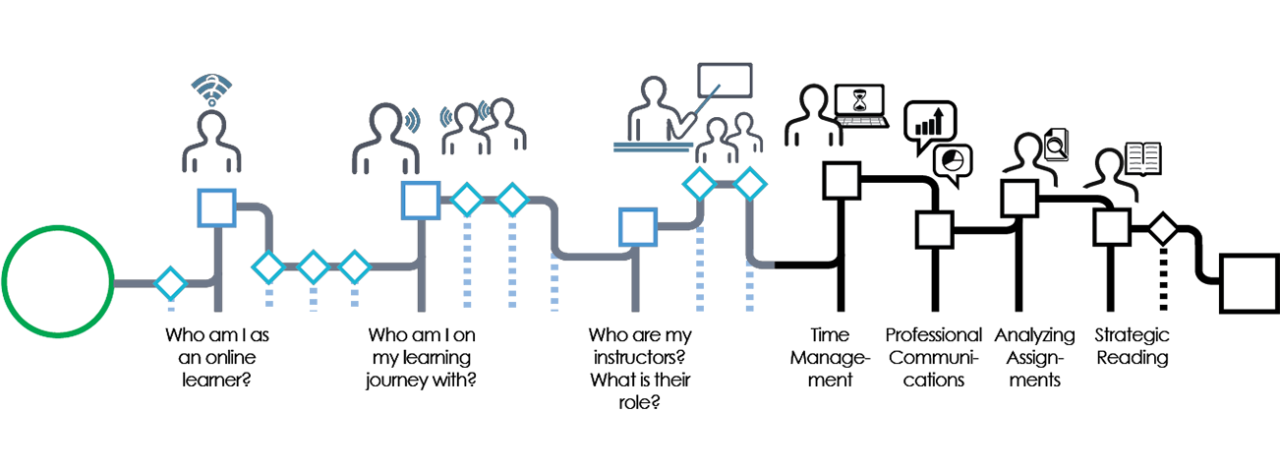

(Image: Time Management © Graeme Robinson-Clogg is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license)

Leave a Reply