Anns an t-sreath seo, tha sinn a’ toirt sùil air laoich a rinn adhartas cudromach ann an teicneolas nan cànanan Gàidhealach. Airson an treasamh agallaimh, cluinnidh sinn bho thè Lucy Evans. Tha Lucy air ùr thighinn gu saoghal na Gàidhlig agus gu saoghal teicneolas cànain, ach tha i an sàs ann am pròiseact a bhios glè chudromach san àm ri teachd, thathar an dòchas. Chuir i crìoch san Lùnastal 2020 air MSc ann an Pròiseasadh Cànan is Cainnt aig Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann. Goirid an dèidh sin, thòisich i mar phàirt de sgioba rannsachaidh a bhios a’ feuchainn ris a’ chiad aithneachar cainnt a chruthachadh dhan Ghàidhlig. Thòisich am pròiseact san t-Sultain 2020 le maoineachas bho Shoillse, an lìonradh nàiseanta rannsachaidh airson glèidheadh agus ath-bheothachadh na Gàidhlig. Tha am pròiseact rannsachaidh na chom-pàirteachas eadar Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann, Oilthigh na Gàidhealtachd is nan Eilean (OGE) agus Quorate Technology Ltd. Anns a’ phìos seo, innsidh Lucy dhuinn ciamar a ghabh i ùidh anns a’ chuspair agus ciamar a bhios cuideigin aig nach eil ach glè bheag de Ghàidhlig ag obair air pròiseact toinnte mar seo.

In this series, we look at persons who have significantly advanced the field of Gaelic, Irish and Manx language technology. For the third interview, we hear from Ms Lucy Evans. Lucy has only recently come to the worlds of Gaelic and language technology, but she is involved in a project that hopefully will come to have great importance in the future. In August 2020, she finished her MSc in Speech and Language Processing at the University of Edinburgh. Shortly after that, she joined a research team that is working to develop the first working speech recogniser for Scottish Gaelic. The project began in September 2020 with funding from Soillse, the national research network for the maintenance and revitalisation of Gaelic language and culture. The research project is a collaboration between the University of the Highlands and Islands, the University of Edinburgh and Quorate Technology. In the interview, Lucy tells us how she took an interest in the subject of speech and language technology and how someone with little Gaelic, at present, is able to work on such a complicated project.

Interview with Lucy Evans

Agallamh le Lucy Evans

“You’ve recently joined the research team developing an automatic speech recogniser for Scottish Gaelic. Tell us a little bit about your background. For example, where are you from, and what got you into language technology work?”

Lucy Evans

I grew up bilingually in Switzerland, speaking English and Italian, before moving to the UK for secondary school. Being bilingual at a young age definitely sparked a curiosity about language, and I went on to study French and Linguistics at the University of Leeds. There, I absolutely loved studying linguistics, so started looking for jobs where I could apply my knowledge from the subject. This led me to discover the field of computational linguistics, and through this I found the MSc in Speech and Language Processing. The MSc encompasses all aspects of language technology, and so was a perfect introduction to the field!

“You’ve just finished the MSc in Speech and Language Processing at the University of Edinburgh. What did you find particularly interesting about the course? Do you have any advice for someone who is thinking about doing it in the future?”

Honestly, I found the whole course really interesting! I was constantly in awe of what I was learning – the interface between computer science and linguistics is niche, and so the techniques used are really specialised. I just find the ability of computers to pick up on all the complexities of language so interesting.

My advice for anyone taking the MSc in the future is simply to be prepared for a really intense year – you’ll be challenged constantly, not only academically, but with time management too. Having said this, the stress is definitely worth it! The course covers a huge amount of content in such a short period of time, which means you’ll be left with a really strong background in the field. A second piece of advice is to get friendly with your peers – there is such a sense of community within the course, and this is undoubtedly one of the loveliest aspects of the MSc. You’ll also get a huge amount of support from Simon King, the course director – make the most of this. Everyone really is there to help and support you, and there is so much more to the MSc than just the course content.

“For those not involved in speech technology, it might seem incredible that someone without Gaelic could develop a speech recogniser for the language. Can you explain how this is possible? And how is working with a minority language going to be different from working with a large language like English?”

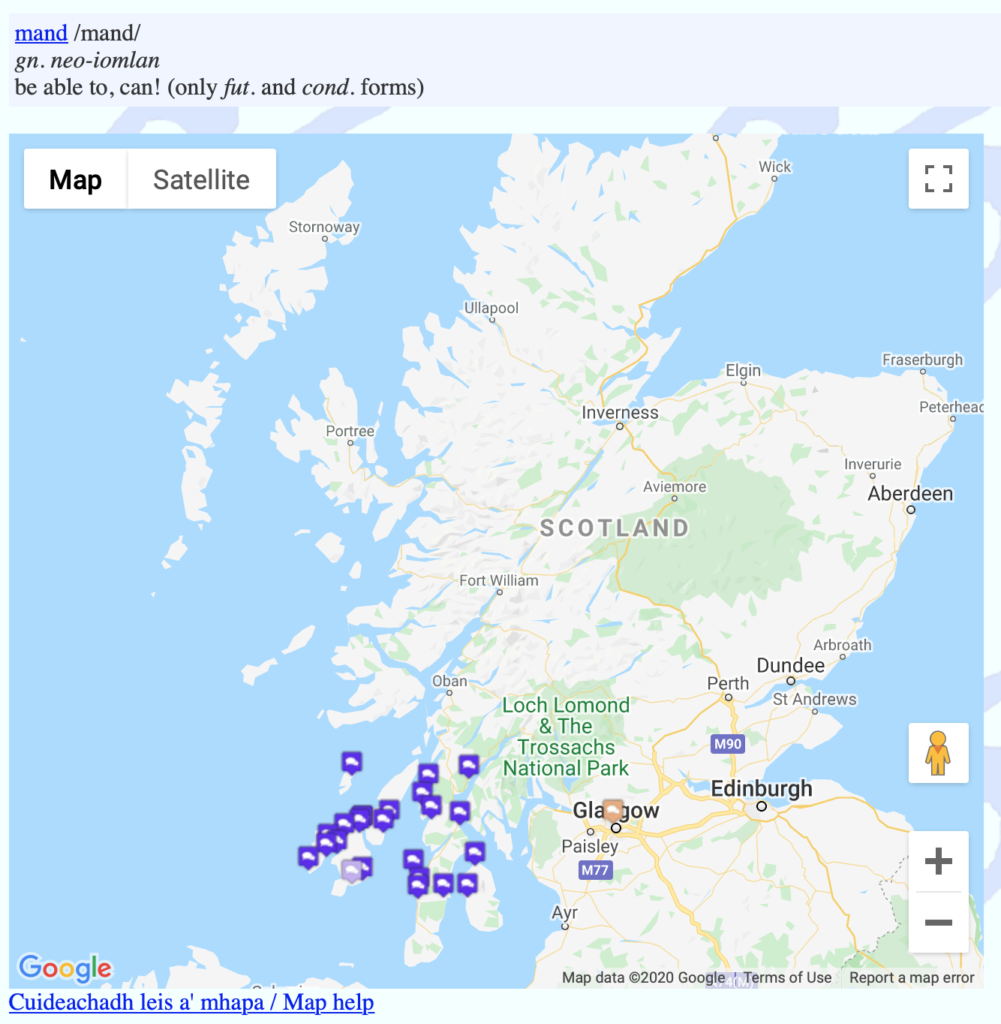

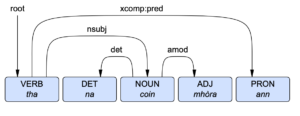

As long as you have the necessary resources, it’s only the computer that has to do the language learning! One of the resources I’m talking about here is the dictionary – which essentially maps any written Gaelic word to its phonetic pronunciation. Using this and some transcribed speech data, we can split the speech into its smaller phonetic units, depending on the words in the transcription. Then we train the speech recogniser to learn what these smaller units generally sound like. When new speech is input to the speech recogniser, it can use this lower-level acoustic knowledge to predict which phones (and consequent words) make up the input speech. In this way, as long as you have appropriate (and high-quality) resources, you don’t actually need to learn the language you’re working on – the computer can do that itself!

Working with a minority language adds a challenge in that we won’t necessarily have these resources available. Luckily, for Scottish Gaelic, a digital dictionary has already been created. But this is definitely not the case for most minority languages, making the task significantly harder for non-native speakers to attempt. Furthermore, good quality, transcribed speech data is generally not so easy to come by in minority languages. In the world of machine learning, the general pattern is that the more data you have, the better your system will be. So, with less data available for these languages, it’s harder to get a better system up and running. But there are many mediating methods we can use to boost the performance of a low-resource system – it’s really about finding what works best for the dataset.

“In your own lifetime, you’ve seen language technology change and permeate how we work and live. What’s been your own experience of the changes that it has brought?”

When I was younger, I used language technology but was never really aware of what was going on in the background. Take something like a sat-nav: this is probably one of the first speech technologies I came across, and I remember just laughing about the robotic quality of the synthesised speech – I had no idea how complex the problem actually is! But the amount this has progressed in the last 10 years is crazy – it’s really impressive to see how far things have come in such a short time. For example, we can now ask a mobile phone any question and have it answer us instantly, in near-perfect speech. Things like predictive text and spell-check are other language technologies that are now so embedded in my day-to-day life that I almost forget the complex things they’re doing behind the scenes.

“What are your predications for language technology in the year 2050? If you had your own way, what would you like to see by that time?”

This is a tricky question – considering just the changes in my lifetime, who knows where we’ll be in 30 years from now! In an ideal world, I’d love to see language tech being used more to help people and cultures. This project is an example of that – creating modern technology for endangered languages is an important way to revitalise and preserve those languages! Something I’m also really interested in is using technology to help people with speech disorders, which is definitely something that’s gaining momentum at the moment – it’ll be interesting to see how this can be further improved in years to come.