By Catherine Banks

As the Decoding Hidden Heritages project is nearing the end of its digitisation and metadata collection stage, this is a good opportunity to share some insights from the project on the importance of archival work for the representation of women’s heritage. While the project’s main focus is on the narrative traditions of Scotland and Ireland, valuable information has also been discovered that has wider cultural implications, such as the influence of gender on narrative traditions. These discoveries have been made possible by the digitisation process because it has allowed a re-examination and re-documentation of the archive’s collection. As part of this process at the School of Scottish Studies Archives, I have been able to employ what Prof Melissa Terras terms feminist digitisation practices, which ‘are both an attitude, and an application of technology in an efficient way’.[1] She described this practice as ‘an act of owning women’s history, using digital means, to collate information and histories that the mainstream – for whatever reason – has not tackled’.[2] For this project, that has involved ensuring that women’s material in the archive is accessible to and discoverable by the public through digitisation and accurate metadata collection.

While digitising the Tale Archive I discovered several unique factors that affected women’s presence, or rather their absence, in the archive. In particular, I noticed distinct documentation issues with the archive’s material relating to women. The most significant of these issues was the erasure of women’s names in archival documents and metadata.

There are four distinctive scenarios in which women’s names have been erased:

- The documents lack women’s first names.

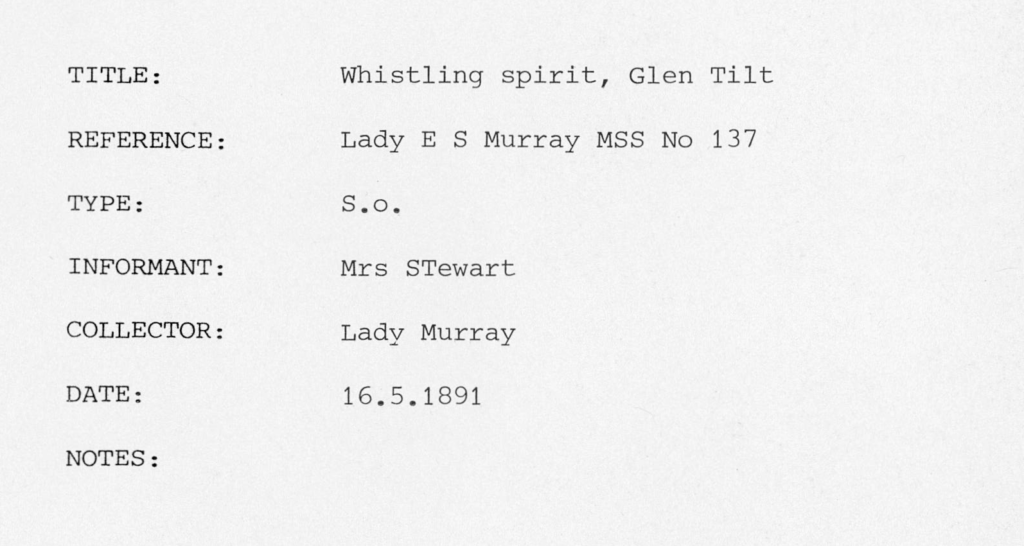

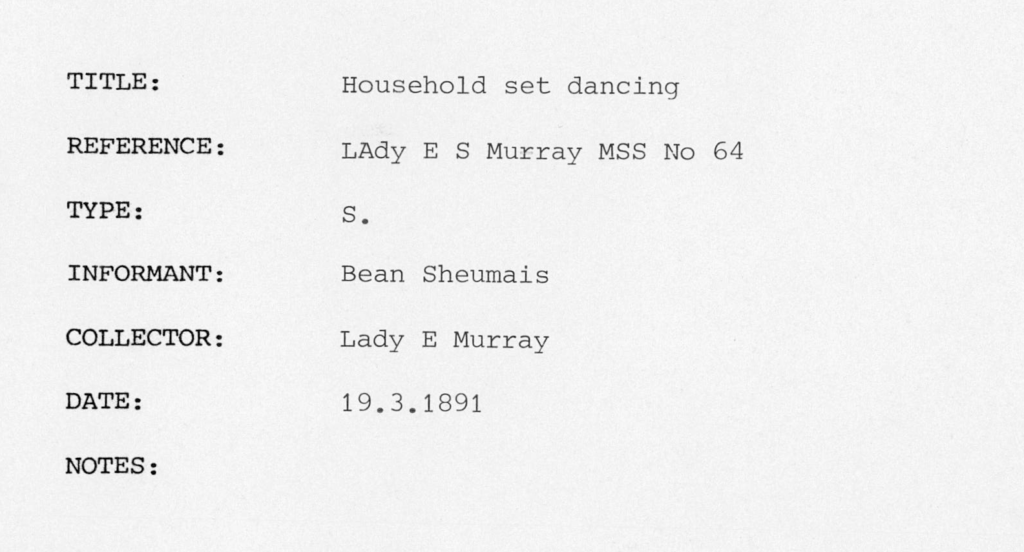

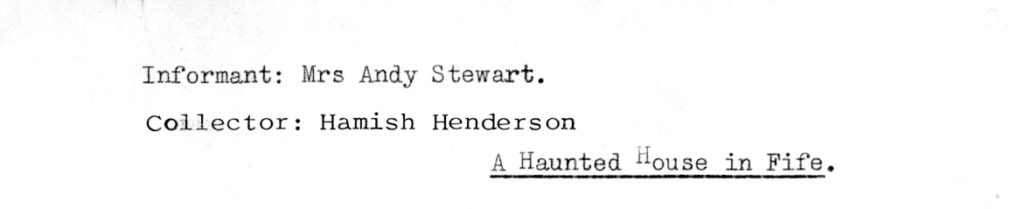

The most common erasure of women’s names in the archive is the use of only women’s surnames, particularly their married surnames, for example Mrs. Stewart. In SSSA_TA_WT042_001 the informant is only listed as Bean Sheumais (‘Wife of James’). This is most likely because that was how these women would have given their names to the collectors, as was the social practice at the time.

- Their husband’s full name is used in lieu of women’s names.

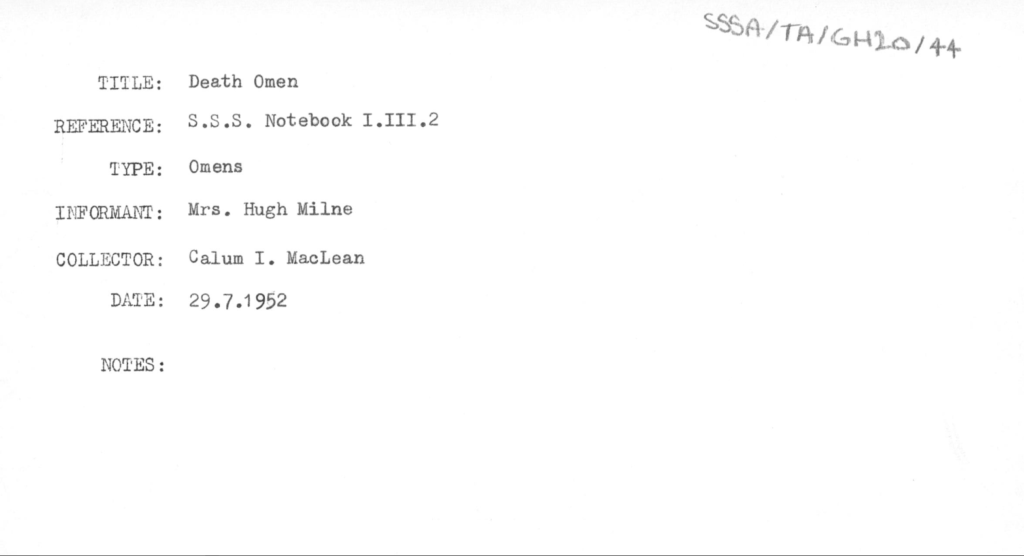

The next most common form of women’s names is their husband’s full name used as their married name, for example Mrs. John MacDonald. In some cases, married women’s first names have been discovered and their full names are included in the metadata. For example, Mrs. Hugh Milne has been recorded as Bella Milne in the project database.

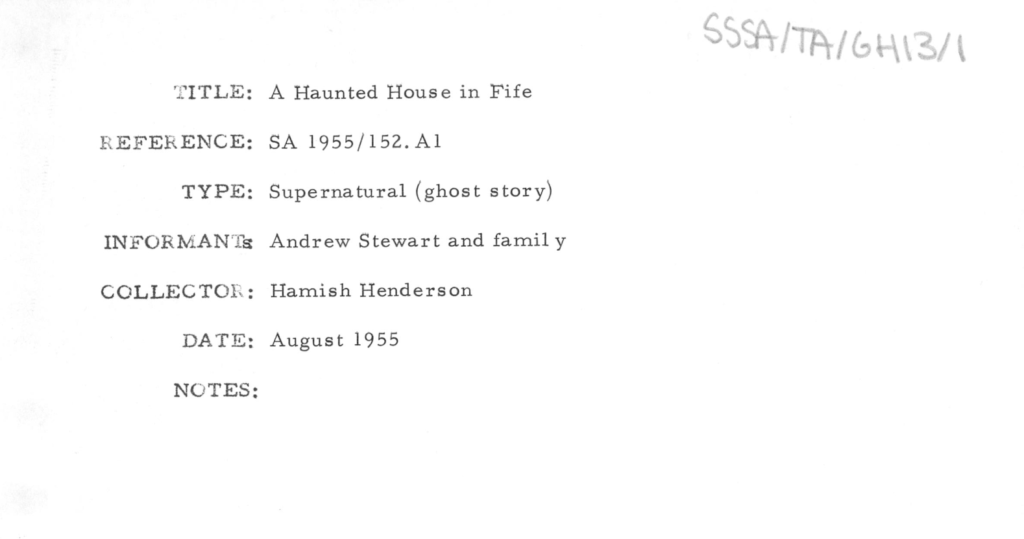

The influence of gender on the documentation of names in these records is made clear in SSSA_TA_GH013_001. The metadata for this transcription records the informant as ‘Andrew Stewart and family’ but the document itself listed it as Mrs. Andy Stewart. Despite the fact that this story is told by Mrs. Stewart about her own experience with a ghost, the metadata recorded her husband as the main informant, erasing Mrs. Stewarts’ ownership over her story. When her husband and son interject into her story, the transcript states ‘Carol Stewart, their son, takes over’ and ‘Andrew takes over’ but, rather than use her full name, it says that the ‘story returns home to Mrs. Stewart’. Each of the male members of the Stewart family have their full names recorded while Mrs. Stewart does not. As a result of re-examining this material, the metadata has been corrected and Mrs. Stewart’s story is now properly recognised in the archive.

- The names are unrecorded.

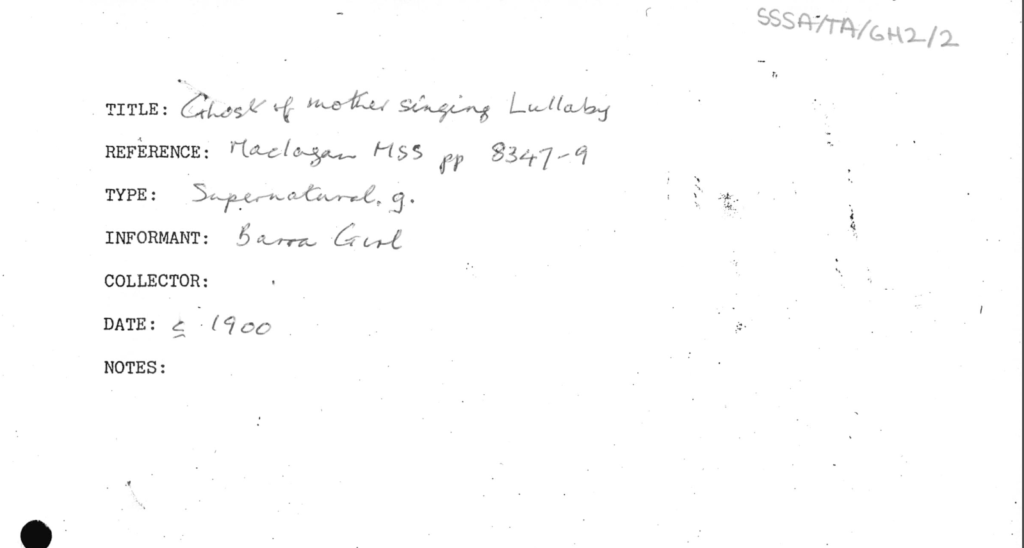

In much of the material, women have shared their stories anonymously. This makes it impossible to document who they are. Women are often referred to as ‘girls’ such as ‘Barra Girl’ (SSSA_TA_GH002_002) or ‘a girl who was native of Glenurqhart’ (SSSA_TA_WT043_002) without their names recorded. Yet, even in these cases it is still important to document the informant’s gender in the metadata. For example, one informant was listed as a ‘Native of Lochcarron’ in SSSA_TA_WT037_015. However, by reading their story it can be ascertained this person was a woman, because she states, ‘when they sent me … I was a young girl at the time’. By documenting their gender in the metadata, at least we are able to accurately acknowledge these women’s presence in the archive.

- They are not named in the archive’s metadata but are present in documents.

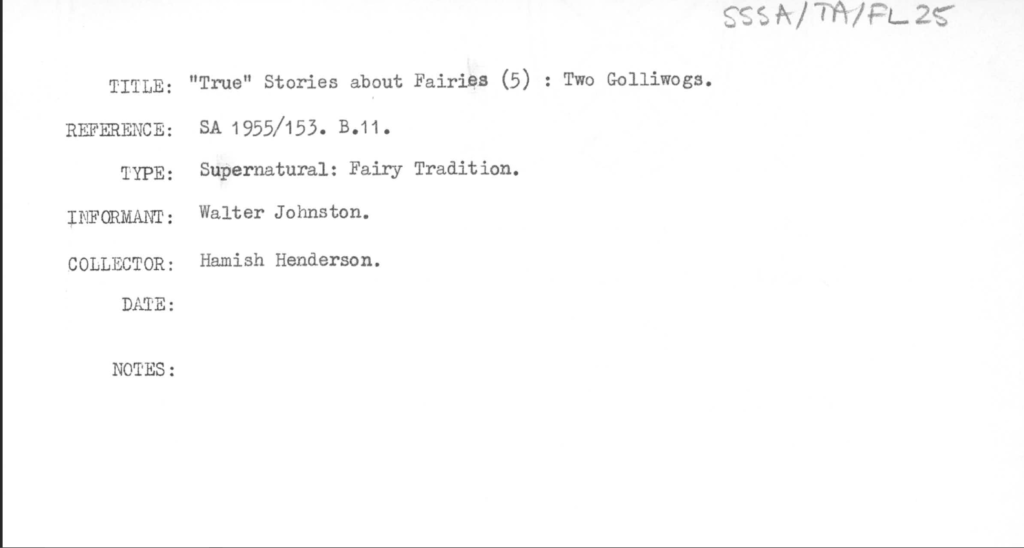

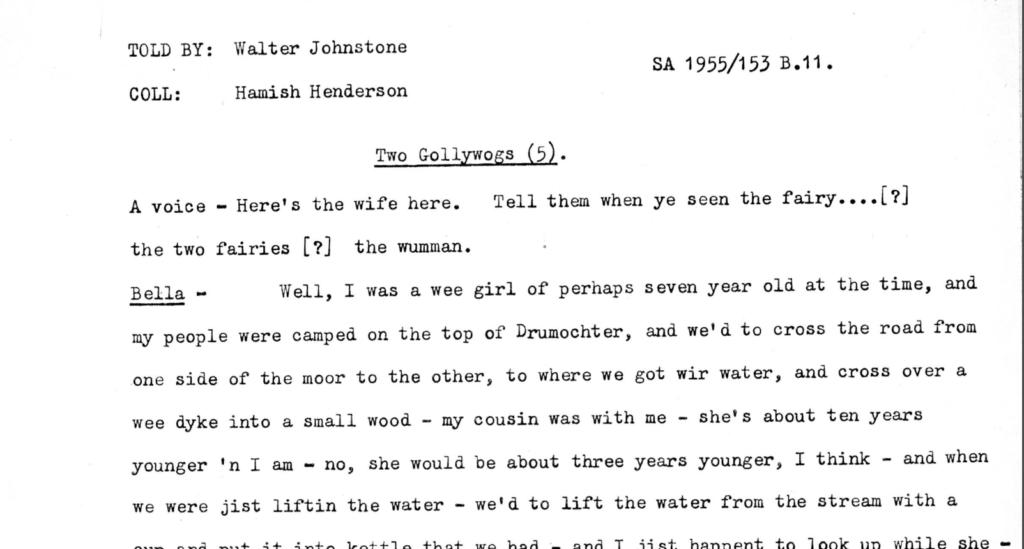

One of the most significant examples of a woman’s erasure from the archive is SSSA_TA_FL025. This document and its metadata records Walter Johnson as the informant of a transcription. However, the transcription is actually of Bella Higgins telling her personal experience of meeting a fairy [Ed. noted here using the dated and offensive term ‘golliwog’]. Even though it is only Bella speaking, her story had been attributed to Walter Johnson. As a consequence of this incorrect documentation, her voice had been hidden in the archive.

Similarly, in a series of transcriptions by John Stewart and his wife Maggie Stewart (SSSA_TA_GH001_022, 23, 25), John was recorded as the only informant. Even though Maggie was present in them as well, her contributions to their stories were unrecognised. As a result of the careful examination of these documents while they were digitised, these women’s contributions were uncovered and are now appropriately documented in the collection’s metadata.

While in some cases these documentation issues may seem small, they have significant consequences. Women’s names being unrecorded or partially recorded in the archives makes tracing women’s histories and family lineages extremely difficult and often impossible. For example, it is impossible to ascertain from the documentation whether a woman recorded as Mrs. MacDonald is the grandmother, mother, wife or sister-in-law to Mr. John Macdonald because all these women would have been referred to identically. Similarly, when women have no name recorded at all, their contributions to the archive are unidentifiable.

The exclusion of these women misrepresents the material within our archives, presenting the collection as more male dominated than it is. Not only is their re-inclusion into the archive’s metadata important as an act of justice for these women, but it also enriches and expands the historical research and data that can be produced from the archive. As historians Andrew Flinn, Mary Stevens, and Elizabeth Shepherd have argued, ‘the archives that are “chosen” for survival, the terms in which they are described, and the processes by which these decisions are made, do ultimately impact on the collective memory and public histories that are produced from them’.[3]

This is particularly important in the context of the increasing trend in historical research, where historians seek to write women who have been hidden in accounts back into history. A recent example of this is a biography of George Orwell’s wife, ‘Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life’ by Anna Funder. She points out that in Orwell’s novel Homage to Catalonia, written while Orwell and his wife were in Spain, he ‘mentions “my wife” 37 times but never once names her. No character can come to life without a name’.[4] However, Funder was able to reconstruct the life of Eileen when she went ‘back to the biographers’ footnotes and sources and into the archives and found details that had been left out. Eileen began to come to life’.[5] Thus, there is immense value in archival sources which is still being discovered today and archivists play a vital role in ensuring that women’s history in these archives does not remain hidden. It is therefore important to seize the opportunity that digitisation projects such as this present to employ feminist digitisation practices on archival collections to uncover women’s hidden histories and ensure their posterity for the future.

The DHH team would like to thank Catherine for her important and timely blog and her excellent contributions to the project.

Bibliography

Flinn, Andrew, Mary Stevens, and Elizabeth Shepherd. “Whose Memories, Whose Archives? Independent Community Archives, Autonomy and the Mainstream”. Archival Science 9, no. 1-2 (2009)

Funder, Anna. “Looking for Eileen: how George Orwell wrote his wife out of his story”. The Guardian, 30 July 2023. Accessed 4 October 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jul/30/my-hunt-for-eileen-george-orwell-erased-wife-anna-funder.

Melissa Terras. “Interview With Professor Melissa Terras On Feminist Digitisation Practices And The Future Of Our Digital Cultural Heritage”. The University Of Edinburgh Futures Institute, 6 January 2023. Accessed 4 October 2023. https://efi.ed.ac.uk/interview-with-professor-melissa-terras-on-feminist-digitisation-practices-and-the-future-of-our-digital-cultural-heritage/.

Links to images

https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/person/1864?l=en

https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/person/639?l=en

Footnotes

[1] Melissa Terras, “Interview With Professor Melissa Terras On Feminist Digitisation Practices And The Future Of Our Digital Cultural Heritage”, The University Of Edinburgh Futures Institute, 6 January 2023, accessed 4 October 2023. https://efi.ed.ac.uk/interview-with-professor-melissa-terras-on-feminist-digitisation-practices-and-the-future-of-our-digital-cultural-heritage/.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Andrew Flinn, Mary Stevens, and Elizabeth Shepherd, “Whose Memories, Whose Archives? Independent Community Archives, Autonomy and the Mainstream”, Archival Science 9, no. 1-2 (2009): 76.

[4] Anna Funder, “Looking for Eileen: how George Orwell wrote his wife out of his story”, The Guardian, 30 July 2023, accessed 4 October 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jul/30/my-hunt-for-eileen-george-orwell-erased-wife-anna-funder.

[5] Ibid.

Leave a Reply