This week’s blog post will take a behind-the-scenes look at what’s involved in digitizing an archival collection.

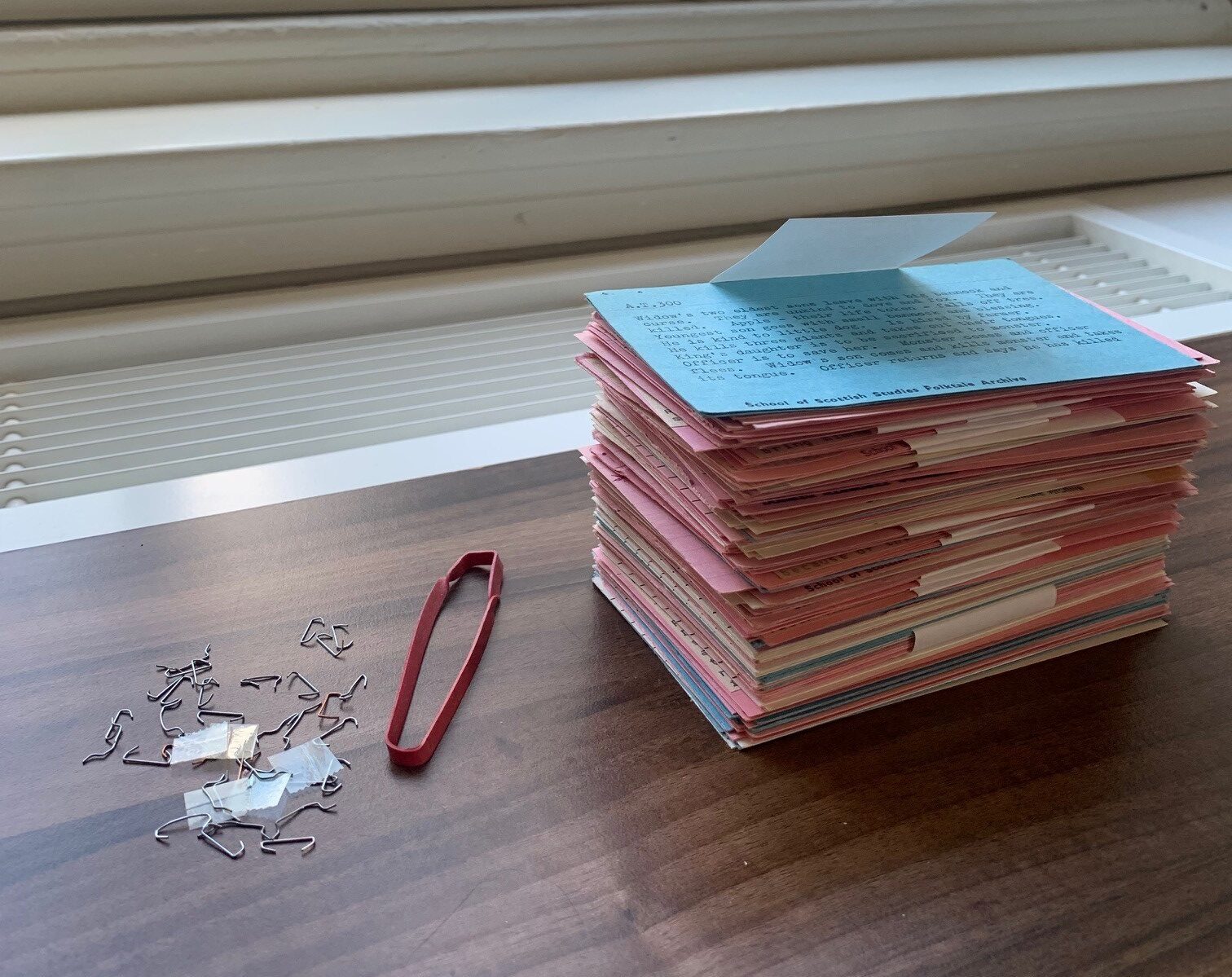

My job in the Decoding Hidden Heritages Project is to scan and document the contents of the Tale Archive here at the SSSA. The Tale Archive is comprised of paper documents separated into folders depending on their classification (ATU number, Romantic Tales, Supernatural Tales, etc.). There is also a collection of corresponding index cards for these documents.

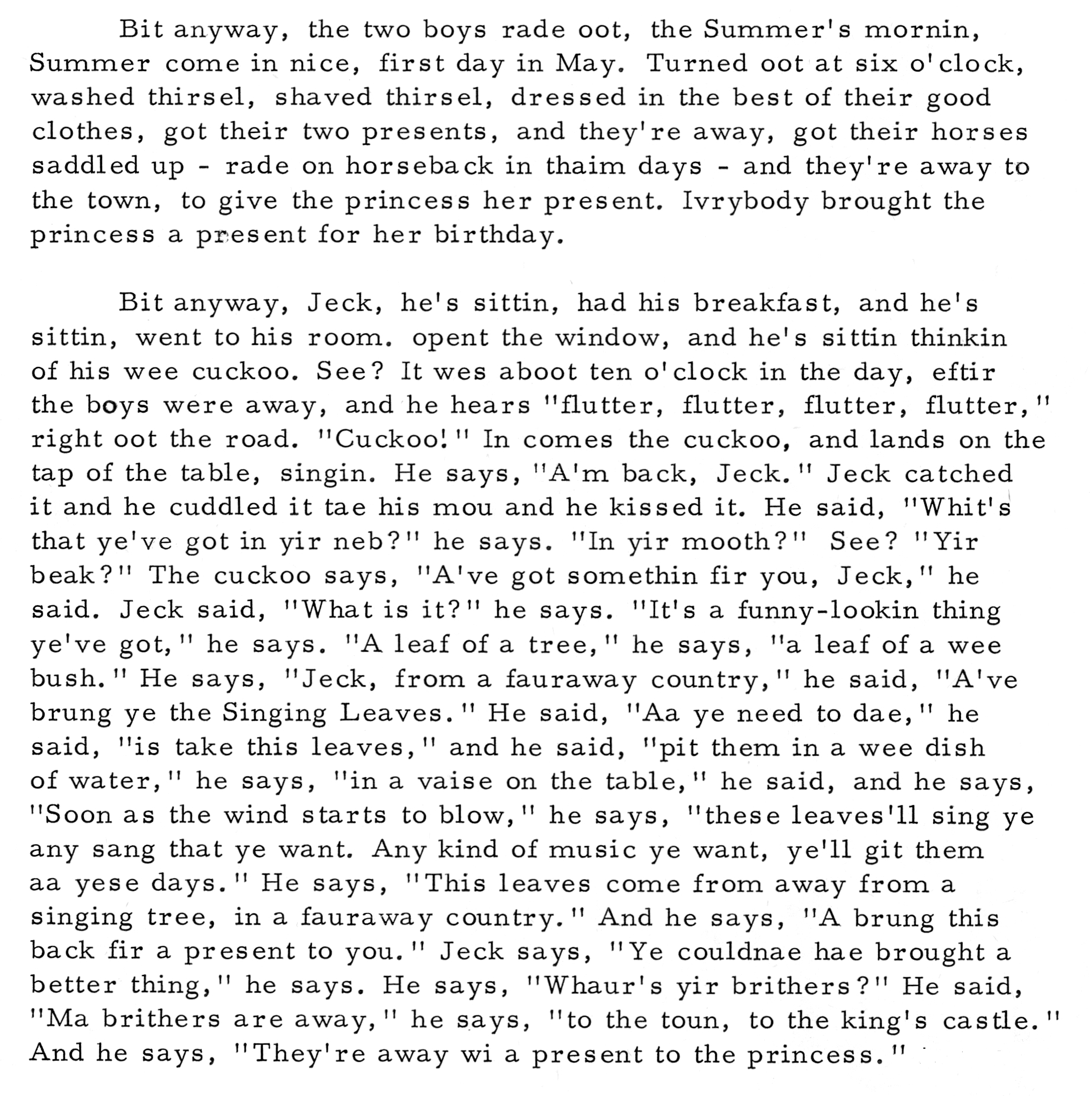

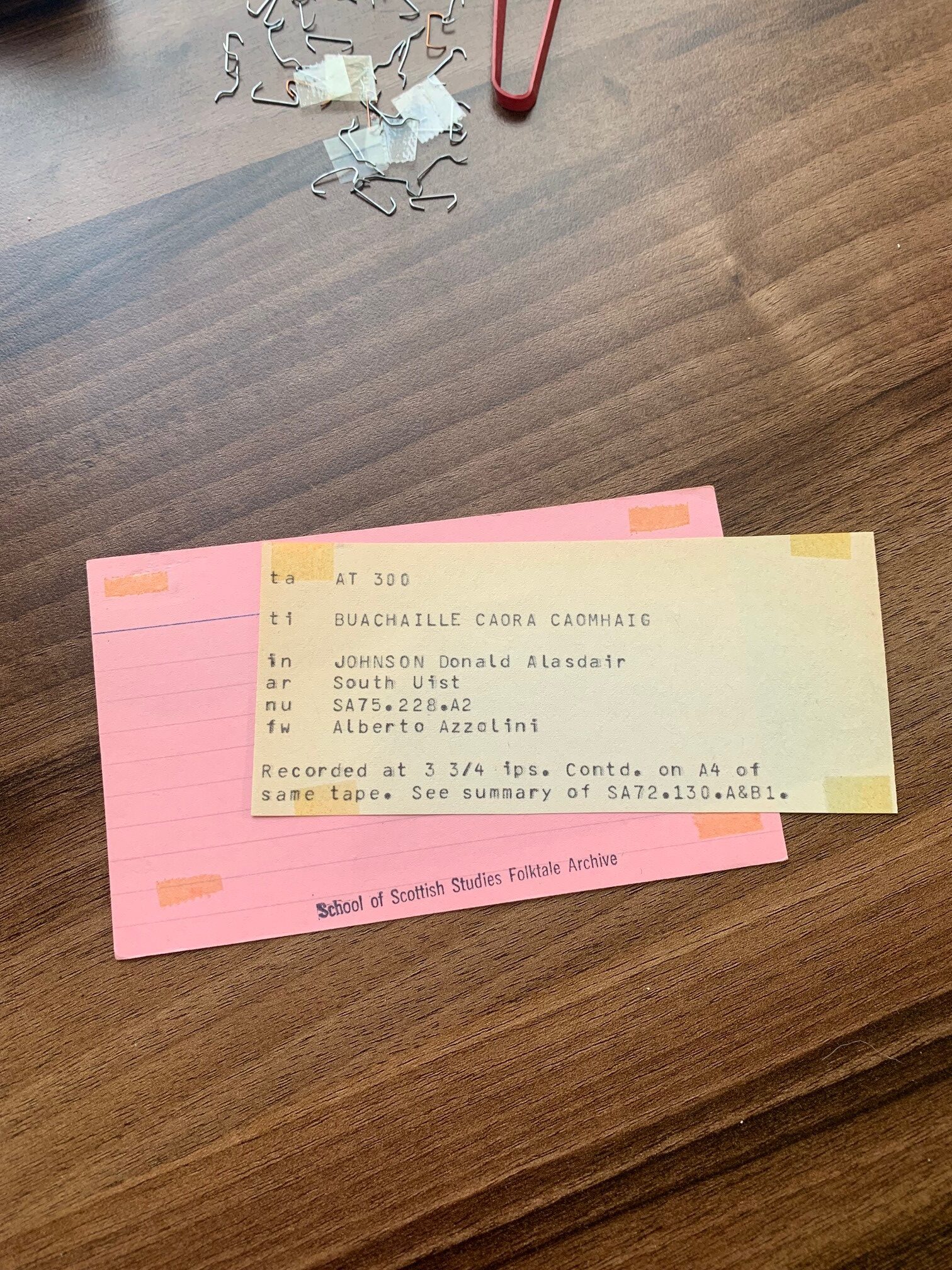

The Tale Archive at the School of Scottish Studies Archive

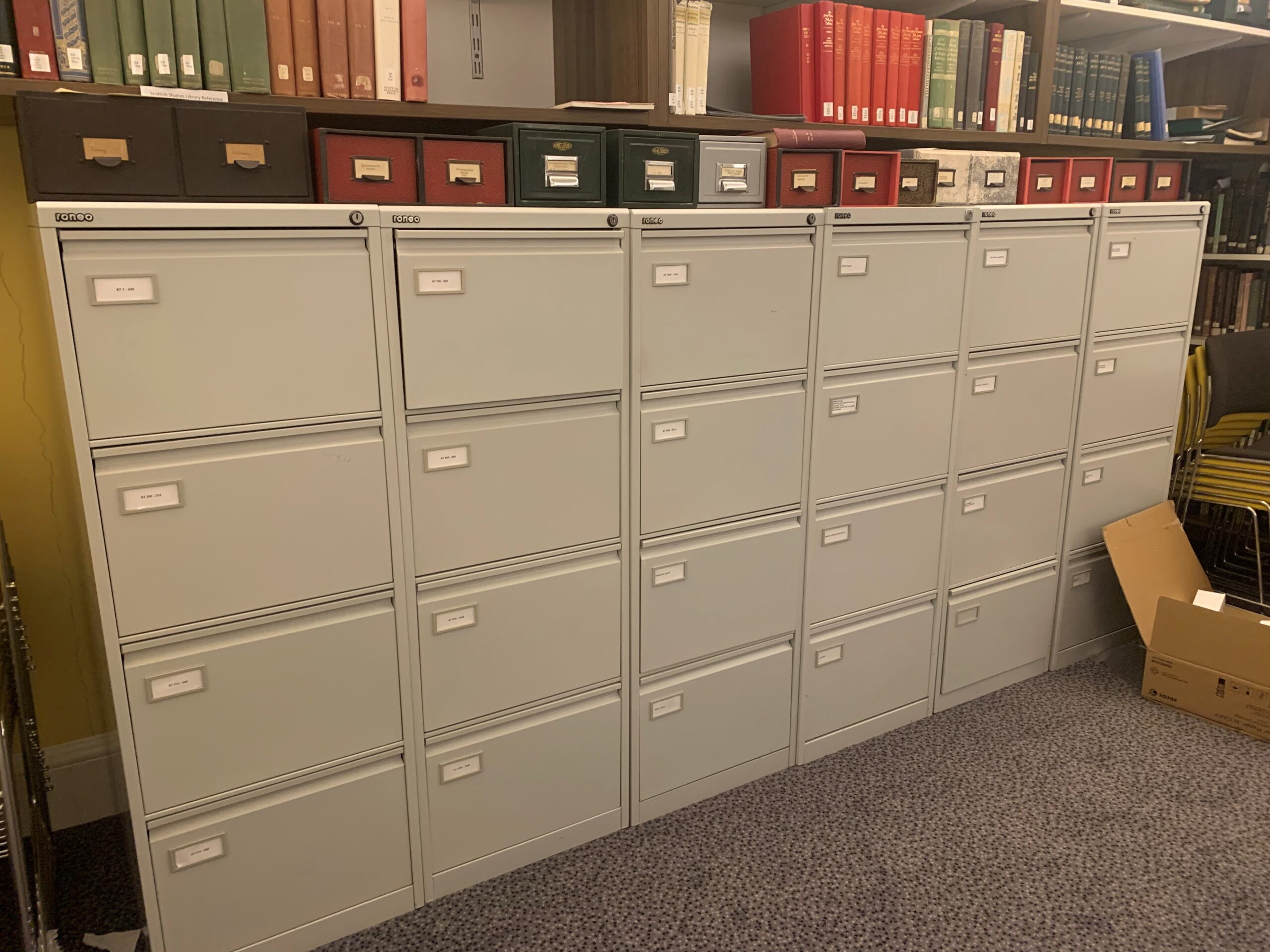

As with most archival collections, various stationary items like staples, rubber bands and tape have been used over the years. Although their use was innocent and common-sense at the time, people looking after historic and archival collections now are aware that these items can present conservation issues. Staples can distort and tear paper and card, and metal has the potential to react chemically with its environment and certain materials it comes into contact with. Plastics and rubbers are particularly notorious for deteriorating in historic collections, and sometimes in unexpected ways. Deterioration of plastics is still a relatively new area of study among conservation experts, and methods of dealing with deterioration and alteration of plastic collections will continue to evolve in the coming years.

“Plastics are a new class of materials and their individual weaknesses are little known and often unexpected. Traditional display and storage methods accelerate deterioration of plastics, and the ensuing chemical and physical damage can be unattractive, highly corrosive, irreversible—and largely un-treatable. Because of the diversity and versatility of plastics, they have been used in a huge range of common objects since their introduction in the 19th century. Unfortunately, for the first part of their history, their long-term properties were not well understood. Older plastic objects can deteriorate more rapidly and in a greater variety of ways than those made from traditional materials. More recent plastics may also deteriorate rapidly as a result of planned obsolescence, such as biodegradability.” – Canadian Conservation Institute Guidance on Caring for Plastics and Rubber

Rubber reacts to oxygen over time and can become brittle and sticky. The rubber band in the photo below had to be carefully taken off the affected index card to ensure no text was lost.

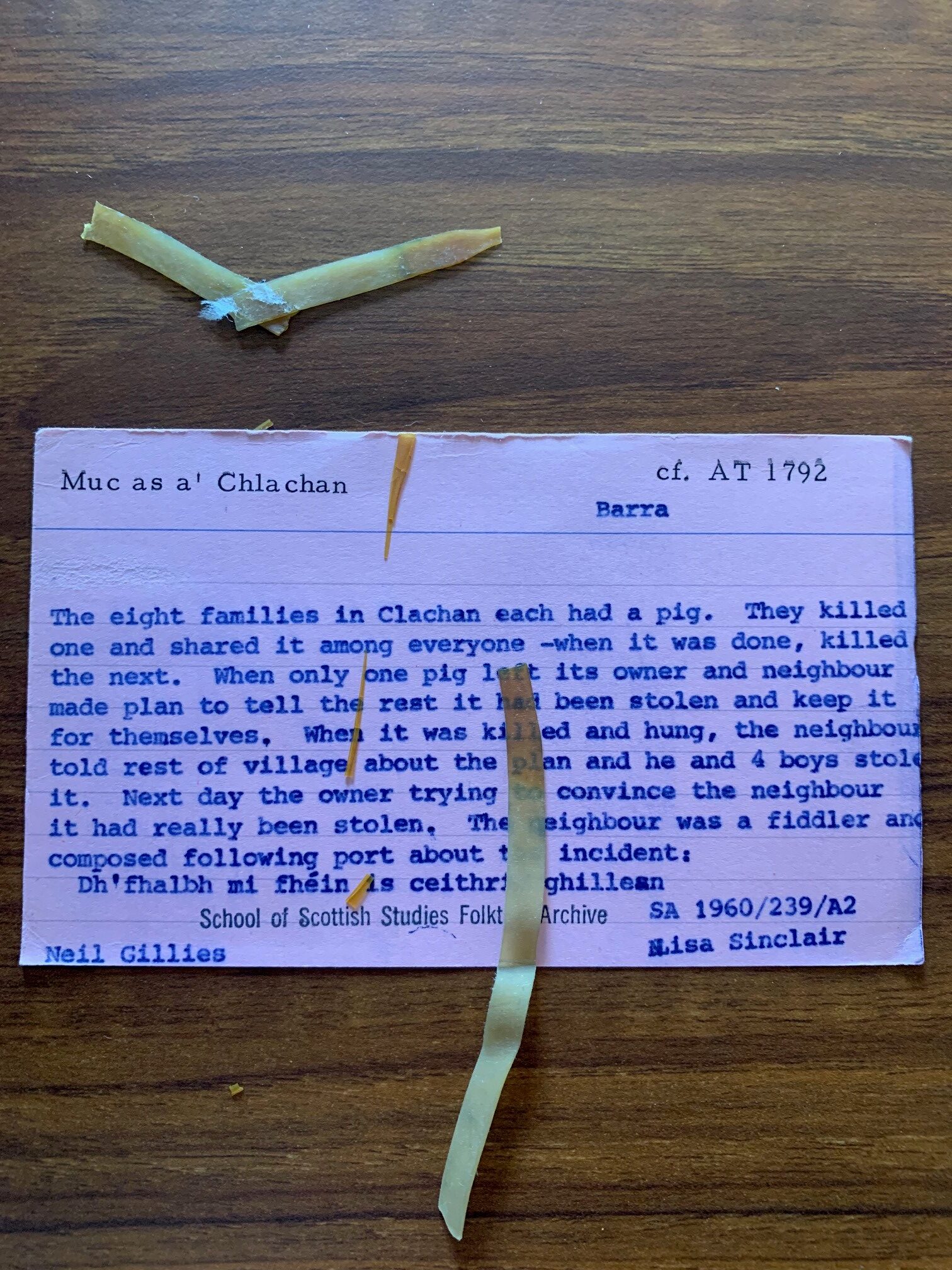

Sticky tape will lose its adhesion over time and will come lose and discolor paper as can be seen in the photos below.

Projects like this one are a great opportunity for collections to be sifted through and to deal with any conservation issues present. As I go through the paper and cards to prepare them for scanning, I carefully remove any items that will prevent the documents from being scanned safely or that may harm them in storage over time. Paperclips and rubber bands are carefully removed and replaced with acid-free paper, which will prevent any further deterioration so the documents can stay legible for future generations to benefit from. If the paper/card is fragile and removing the deteriorated elements would do further damage, then it is left as found. I also have access to a special overhead scanner for these documents that takes a scan from above and does not come into contact with the document. Feeding fragile documents through the usual scanner could destroy them – and probably the scanner, too!

A bit of a top tip from the National Archives’ Managing Mixed Collections Guidance to use at home is to not store photographs next to rubber: “Vulcanised rubber emits hydrogen sulphide and carbonyl sulphide, gaseous pollutants that are the main agents responsible for tarnishing silver and causing photographs (which include a silver component) to fade and yellow. Rubber bands are made from vulcanised rubber, so it is important to ensure they are not used in close proximity to photographic materials.”

Have questions? Feel free to comment on the post and I will happily try to answer!

Further reading:

Care of Objects Made from Rubber and Plastic – Canadian Conservation Institute

Plastics? Not in My Collection – V & A Conservation Journal

Lorg mi fiù aon sgeulachd far a bheil an abairt ’ga chleachdadh sa chaochladh, ag innse do chuid-eigin nach eil fàilte romhpa ann an àite. Anns an sgeulachd, tha Séadanda dìreach air a’ chù aig Culainn a mharbhadh agus tha Culainn a’ faighneachd dheth cò esan agus nuair a chluinneas e cò esan, tha e a’ freagairt

Lorg mi fiù aon sgeulachd far a bheil an abairt ’ga chleachdadh sa chaochladh, ag innse do chuid-eigin nach eil fàilte romhpa ann an àite. Anns an sgeulachd, tha Séadanda dìreach air a’ chù aig Culainn a mharbhadh agus tha Culainn a’ faighneachd dheth cò esan agus nuair a chluinneas e cò esan, tha e a’ freagairt