Author: Alistair Bullen

Background to the project and the think aloud pilots

The INFO-BC (Supporting shared decision making in secondary breast cancer) project is continuing to make great progress towards releasing a full-scale survey to patients, health professionals and the general public. INFO-BC is a planned survey which aims to understand preferences for secondary breast cancer treatments, you can find out more here. The study recently completed the think-aloud pilot stage of the project. 10 patients and 5 health professionals piloted early versions of the questionnaire whilst being asked to talk through their decision making. The feedback we received during the pilots allowed us to make improvements to the questionnaire, we then showed the improved version of the questionnaire to the next respondents. Changes were often made to the attributes and levels in the Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE). Attributes refer to the factors of treatment which were included in the survey and levels refer to the different available options for the attribute.

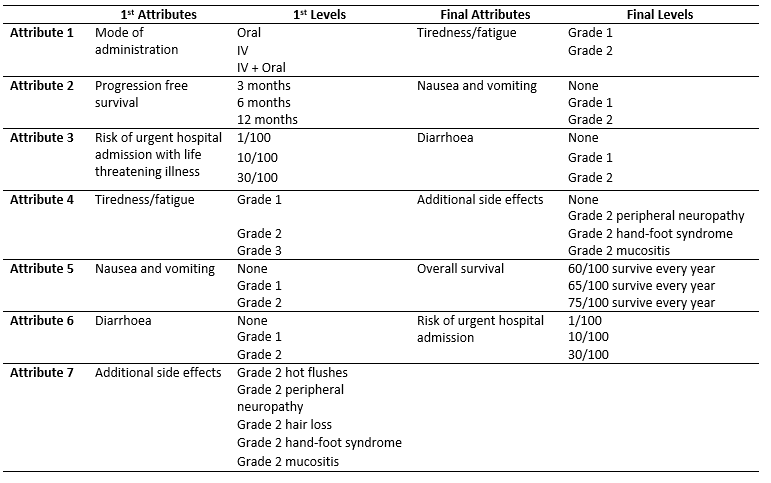

The table below illustrates how the attributes and levels changed as a result of the think-aloud pilot. Diarrhoea didn’t change significantly but you can see that it is composed of three levels; None, Grade 1 and Grade 2. Grades refer to the official Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) which are used by health professionals worldwide to classify medical problems, symptoms, and side effects. Health professionals tend to be familiar with CTCAE criteria so were told that the grades themselves, for patients they were given a description which effectively translated the grade into standard language. There were many changes which we implanted as a result of our piloting, here I will discuss three key changes which were of particular importance.

The key changes

The first key change between the first and final version of the questionnaire was the removal of the mode of administration attribute. The decision to remove the attribute was partly because several respondents told us that the attribute was not important when compared to the other attributes. Also, we were already uncertain about whether to include the attribute, several studies similar to ours which had used a mode of administration attribute in the past found it to have little effect on people’s choices, and there is already a significant body of literature on people’s preferences for mode administration.

The second key change was that progression-free survival (PFS) was swapped for overall survival (OS). We initially failed to effectively communicate to patient respondents what PFS meant. PFS is an important measure for those who study cancer. PFS is the length of time treatment can control a cancer before it begins to grow at a clinically significant rate. It does not necessarily ensure that a patient’s life expectancy or quality of life improve. We realised that it was hard to disentangle the concepts of quality of life and length of life from patients’ interpretation of PFS. This meant that patients who chose options with better PFS weren’t necessarily interested in PFS itself, they may have been interested in a better quality of life and longer survival. A recent publication by Michael J. Raphael in Canada also came to our attention which assessed to the use of PFS in studies like ours, it argued that PFS was not being effectively communicated to patients. All of these factors considered we decided that it was simpler to ask patients to consider OS rather than PFS.

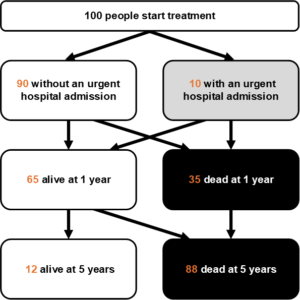

The third key change was that risk of urgent hospital admission (UHA) was combined with OS. In the early versions of the questionnaire, the respondents were shown a graphic of 100 people with some coloured in to represent risk of UHA. In a separate box, patients were shown a separate graphic illustrating the survival prospects at 1 year and 5 years for 100 people. Not only did the graphics for OS prove to be difficult to interpret but we failed to communicate to patients how the two concepts were related. In the early versions of the questionnaire, we intended the risk of UHA to be life-threatening, meaning that there was risk of death. We, therefore, attempted to communicate that the OS prospects were only relevant for individuals who completed treatment and that patients who experienced a UHA were required to stop treatment either because they had died or because treatment had proved too dangerous. This relationship was both difficult to understand and an added complication. It became apparent that we needed to more clearly and simply demonstrate the relationship. The solution we enacted was to present a single graphic as shown below which demonstrated a timeline which first showed how patients experienced a UHA within their first year of treatment, then how many patients could expect to be alive at 1 year, and how many could expect to be alive at 5 years. This solution proved to be easier to understand for respondents.

Concluding remarks

The think-aloud pilots proved to be extremely useful. I spend much time thinking about the precise scenario we are asking patients to imagine and it can be difficult to see what may be confusing to someone looking at the problem with a fresh pair of eyes. I would like to thank Morag McIntyre, the research nurse for INFO-BC, for conducting the pilots. I would also like to thank all of the patients and health professionals who took time out their days to pilot the survey and contribute to this important research.