Anns an t-sreath seo, tha sinn a’ toirt sùil air laoich a rinn adhartas cudromach ann an teicneolas nan cànanan Gàidhealach. Airson a’ cheathramh agallaimh, cluinnidh sinn bho Roibeart MacThòmais. Coltach ri Lucy Evans, the Rob air ùr thighinn gu saoghal na Gàidhlig. Chaidh fhastadh airson còig mìosan ann an 2021 mar phàirt de phròiseact a mhaoinich Data-Driven Innovations (DDI), far a robh an sgioba a’ cruthachadh teicneolas aithneachadh labhairt airson na Gàidhlig. Dh’obraich Rob air inneal coimpiutaireachd ùr-nòsach eile, An Gocair.

Nuair a bhios tu a’ feuchainn ri teicneòlas cànain a chruthachadh airson mhion-chànain, ’s e an trioblaid as bunasaiche ach dìth dàta. Chan eil an suidheachadh a thaobh na Gàidhlig buileach cho truagh ri cuid a mhion-chànanan eile, ach tha deagh chuid dhen dàta seann-fhasanta a thaobh dhòighean-sgrìobhaidh. Tha sin a’ fàgail nach gabh e cleachdadh gus modailean Artificial Intelligence a thrèanadh gun a bhith a’ cosg airgead mòr air ath-litreachadh.

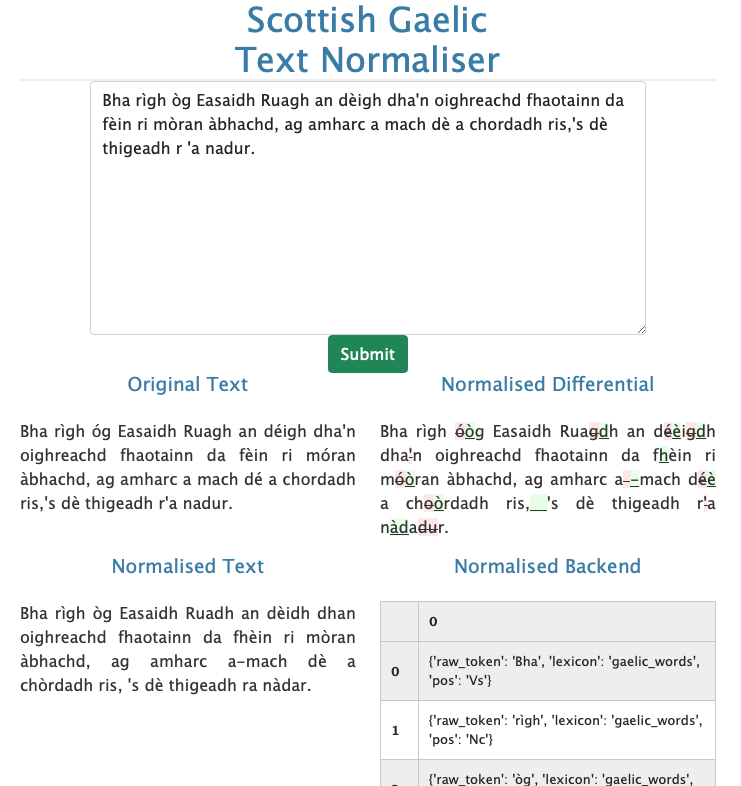

Bidh An Gocair ag ath-litreachadh theacsaichean gu fèin-obrachail – tha e glè choltach ri dearbhadair-litrichidh. Chan eil ann ach ro-shamhla (prototype) an-dràsta agus tha sinn a’ sireadh taic a bharrachd airson a leasachadh. Aon uair ‘s gum bi e deiseil, b’ urrainnear a chur gu feum ann an iomadach suidheachadh, leithid foillseachadh, foghlam aig gach ìre, prògraman coimpiutaireachd eile agus rannsachadh sgoileireil. Cuiridh e gu mòr cuideachd ri pròiseact rannsachaidh ùr a tha a’ tòiseachadh an dràsta eadar còig oilthighean ann am Breatainn, Ameireaga agus Èirinn: ‘Decoding Hidden Heritages in Gaelic Traditional Narrative with Text-mining and Phylogenetics’.

In this interview series, we are looking at individuals who have significantly advanced the field of Gaelic, Irish and Manx language technology. For the fourth interview, we hear from Mr Rob Thomas. Like Lucy Evans, whom we interviewed a few months ago, Rob has come to the world of Gaelic language technology only recently. He was chosen from a strong field to work with us on project funded by Data-Driven Innovations (DDI), in which we were developing the world’s first automatic speech recogniser for Scottish Gaelic. Rob worked on an important strand of this project – developing a brand-new piece of software called An Gocair.

When trying to develop language technology for minority languages, the most fundamental problem is data sparsity. The situation for Gaelic is not as dire as for some other minority languages, but much of the textual data available is outdated in terms of orthography. That makes it impossible to train machine learning models – at least without spending a lot of money on editing spelling.

An Gocair re-spells texts automatically – it’s basically an unsupervised spell-checker with some extra bells and whistles. It is currently only a prototype, however, and we are seeking additional support for its development. Once completed, it will be able to be used in a wide range of contexts, including publishing, education at all levels, as part of other computer programs and within academic research. It will also make a significant contribution to a new research project currently underway between five universities in Britain, America and Ireland: ‘Decoding Hidden Heritages in Gaelic Traditional Narrative with Text-mining and Phylogenetics’.

Interview with Rob Thomas

Agallamh le Roibeart MacThòmais

Tell us a little bit about your background. For instance, where are you from, and what got you into language technology work?

Hello! I’m from a small town in South Wales called Monmouth. I grew up mostly in the countryside, quite far from civilisation. My interest in linguistics probably stems from having a fantastic English teacher in my high school. (Shout out to Mr Jones.) I don’t know if it was the content or how he taught it, but I remember at the time really enjoying the subject and his lessons.

Rob Thomas

I went on to study English Language and Linguistics at the University of Portsmouth. After graduating, I worked for a while at Marks and Spencer as I was not yet sure what kind of career I was looking for. Still kind of directionless, I spent a year and a bit traveling and on return began working in tech support. I managed to find a course in Language Technology at the University of Gothenburg, I had recently found a new interest in programming and this was a great way to merge my new interest and my academic foundation. After a few years living, studying and working in Sweden, I returned to the UK and began the job hunt and was lucky to find the position at the University of Edinburgh.

You mention studying language technology at the University of Gothenburg. What did you find most interesting about the course? Do you have any advice for someone who is thinking about studying language technology?

The course was fascinating and it attracted students from quite a broad background. The first meeting was like The Time Machine by H.G Wells: we were all introduced as the linguist or the mathematician, cognitive scientist, computer scientist, philosopher etc. I think what stood out is that language technology, as a field, relies on input and experience from a multitude of academical backgrounds. This is due to the complex nature of language. I think I would advise anyone who is not from a technical or STEM background to think about how important your knowledge and perspective is for the future of language-based AIs, systems and services. But if, like me, you do come from a humanities background be prepared to dive straight back in to the maths that you thought you managed to escape after you completed your GCSEs.

You are developing a tool for Scottish Gaelic that automatically corrects misspelled words and makes text conform to a Gaelic orthographical standard. That’s impressive for someone with Gaelic, and even more so for someone who doesn’t speak it. How did you manage to do this?

I am quite lucky to be supported by Gaelic linguists and other programmers. I found a way to integrate Am Faclair Beag, an online Gaelic dictionary developed by our resident Gaelic domain expert, Michael Bauer. Alongside the dictionary we translated complicated linguistic rules into something a computer could understand. We have managed to develop a program that takes a text and, line by line, attempts to identify spelling that don’t belong to the modern orthography and searches for the right word from our dictionary. If it has no luck, it then attempts to resolve the issue algorithmically. From the start I knew it was important that I was able to compare the program’s output to work done by Gaelic experts so that I could see whether I was improving the tool or just breaking it.

An Gocair

Since you’ve been born, you’ve seen language technology change and permeate how we work and live. What’s been your own experience of the changes that it has brought?

It has been very interesting witnessing the exponential growth of language technology in the mainstream. It wasn’t until I studied it that I realised how much it was already embedded in websites and services that I’ve been using for years. The more visible applications such as smart assistants are becoming much more normalised in our society. Even my grandma uses her smart assistant to turn on classic FM and put on timers which I think is really cool. My grandma is pretty tech savvy to be fair!

With the dominance of world languages in mass media and on the internet, some would say that technology is an existential threat to minority languages like Gaelic and Welsh. What do you think about this? Are there ways for minority languages to survive or even thrive today?

I think one of the issues in language technology is that most of the work is dedicated to languages that already have huge amounts of resources, for example English. Most of the breakthroughs are being made by large companies that ultimately aim to increase the value of their services. There are a lot of companies that sell language technology as a service (e.g. machine translation) rather than serving communities per se. The latter may not have direct monetary value, but it’s essential to keep that focus in order to allow minority languages to gain access to state-of-the-art technology.

What are your predications for language technology in the year 2050? If you had your own way, what would you like to see by that time?

I imagine smart assistants will be present in more spaces in society, perhaps even in a more official capacity. The county council in Monmouthshire already use a smart chatbot for questions about what days your bins are being collected. Imagine if they were given greater powers such as being able to make important decisions (scary thought). The more time goes on, the more I think we are going to end up with malevolent AIs like HAL from 2001, Space Odyssey, rather than ones like C3PO from Star Wars.

I’m not sure what I would like to see. It would be nice if there was more community-developed and open-source alternatives to what the main large tech companies provide, so a consumer would be able to be sure their data was being used in a safe and respectable way.