Falaire sna meadhan-aoisean

(English Synopsis: How working on a nearly illegible word in a story taken down by Lady Evelyn over a hundred years ago helped solve the mystery of what exactly the term alaire means and whether it has a long or short vowel in Gaelic)

Seadh, ’s Lady Evelyn Stiùbhart Mhoireach à Siorrachd Pheairt a tha mi a-mach air. Bha mi riamh dèidheil oirre ach tha mi air leth taingeil dhi an t-seachdain-sa, oir dh’fhuasgail i snaidhm cànain dhomh a bha a’ cur dragh orm o chionn fhada.

Tha facal car annasach sa Ghàidhlig aig a bheil dà chiall gu gur eadar-dhealaichte a-rèir coltais: falaire. Anns a’ chiad dol a-mach, tha e a’ ciallachadh am biadh a gheibhear aig tìodhlacadh (o shean, b’ e sin aran-coirce, càise agus drama) air neo nàdar de dh’each. Nuair a bha mi ag obair air na h-innteartan seo san Fhaclair Bheag, chùm mi fa leth iad. Ged nach robh mi buileach cinnteach dè am freumh a th’ aig a’ bhiadh tìodhlacaidh, ar leam gur e dà fhreumh eadar-dhealaichte a bha seo ach air an robh, an dèidh linntean, an aon chruth air co-thuiteamas. Gu fortanach, bha co-dhiù am biadh furasta a gu leòr a thaobh cèill is litreachaidh. Ach abair snaidhm a bh’ anns an dàrna facal…

Anns a’ chiad dol a-mach, cha robh e cho furasta fiosrachadh dè dìreach a’ chiall a th’ aige. Lorg mi rudan mar na leanas:

- Dwelly:

alaire, s.f. ‡Brood mare. 2 see falair.

falair, -e, -ean, s.m. Ambler, pacer (of a horse)

falaireach, †† a. Prancing

–d, s.f.ind. Ambling, pacing, curvetting, stately motions of a war-horse, prancing. 2 Canter.

falairich, v.a. Amble - Edward Lhuyd:

56A. Galloping, pacing. Fâlereachd, A[rgyll]. - Am faclair aig an Urr. Tormod MacLeòid:

FÀLAIRE, -EAN, s.m. (Fàl, turf) An ambler, pacer, (of a horse,) a mare - Am faclair aig Athair Ailean MacDhòmhnaill:

FÀLADAIR, 24. a swift rider as if riding a fairy steed or fàlairidh. [Fàlairidh. Heard it used by old men to mean a horse. J.M.]

FÀLAIREACHD, 26, galloping. - DASG

fàlaireachd, another word for ‘marcach’. [NOTES: note added – riding.] - Faclair an Duinnínigh:

FALAIRE, g. id., pl., -RÍ, m., an ambler, a pacing horse.

FALAIREACHT, -A, f., an ambling pace; act of ambling, pacing; American handgallop; the flaw in horses of moving both legs on each side alternately; the gait of a spancelled goat, etc. - MacGilleBhàin:

fàlaire, an ambler, mare, Ir. falaire, ambling horse; seemingly founded on Eng. palfrey. The form àlaire exists, in the sense of “brood mare” (McDougalls’s Folk and Hero Tales), leaning upon àl, brood, for meaning. Ir. falaradh, to amble.

Mo ghaol air Dineen A bharrachd air sin, bha e a’ nochdadh an-siud ’s an-seo ann an seann sgeulachdan mar Buachaille Caora Caomhaig:

“Am bàs os do chionn, a bhéist,” ars esan, “gu dé d’ éirig?” ars esan.

“Ó ’s iomadh rud sin,” ars am fuamhaire, ars esan, “ach chan eil sìon a th’ agam nach fhaigh thu,” ars esan, “ach leig leam mo bheatha,” ars esan.

“Dé,” ars esan, “a bheil agad?”

“Tha,” ars esan, “a h-uile seòrsa agam,” ars esan, “as urrainn duine ainmeachadh,” ars esan. “Tha,” ars esan, “tha fàlairidh agam,” ars esan, “nach do … nach do mharcaich duine riamh a leithid,” ars esan.

Gu dè fon ghrèin a bh’ agam an-seo ma-thà? Nàdar de dh’each math, a-rèir nan seann-sgeulachdan, ach dè dìreach? Agus carson a bha an fhuaimreag a’ dol eadar fada ’s goirid, fiù ann an leabhraichean a bha a’ sgrìobhadh nan stràcan gu cunbhalach? Tha cuimhne agam gun dug mi sùil airson falaire ann an eDIL aig an àm, feuch dè an cruth a bh’ air an fhacal seo san t-Seann-Ghaeilge, ach cha d’fhuair mi dad.

Aig a’ cheann thall, an dèidh dhomh cus ùine a chosg air an aon fhacal mar a thachras uaireannan, chuir mi romham am facal a chur ann le fuaimreag fhada, leis gun robh e a’ nochadh ann an uiread a sgeulachdan mar sin. Ach gach turas a chunnaic mi falaire no fàlaire ann an sgeulachd, chuireadh e dragh orm. Unfinished business, mar a chanas iad sa chànan eile.

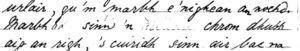

Feasgar an-diugh, bha mi ag obair air ceartachadh agus thàinig mi gu sgeulachd ùr air an robh Lasair Gheug a chaidh a thogail aig tè NicGilleMhaolain ann an Srath Tatha le Lady Evelyn ann an 1891 nuair a bha Gàidhlig pailt san sgìre fhathast. ’S e làmh-sgrìobhadh car seann-fhasanta a bh’ ann, bachallach bachlagach, agus gu math mì-shoilleir ann an cuid a dh’àitichean, lethbhreac de lethbreac de lethbreac is dòcha, mus deach a sganadh. Ach co-dhiù, stiall mi orm gus an dàinig mi gu leth-bhèarn:

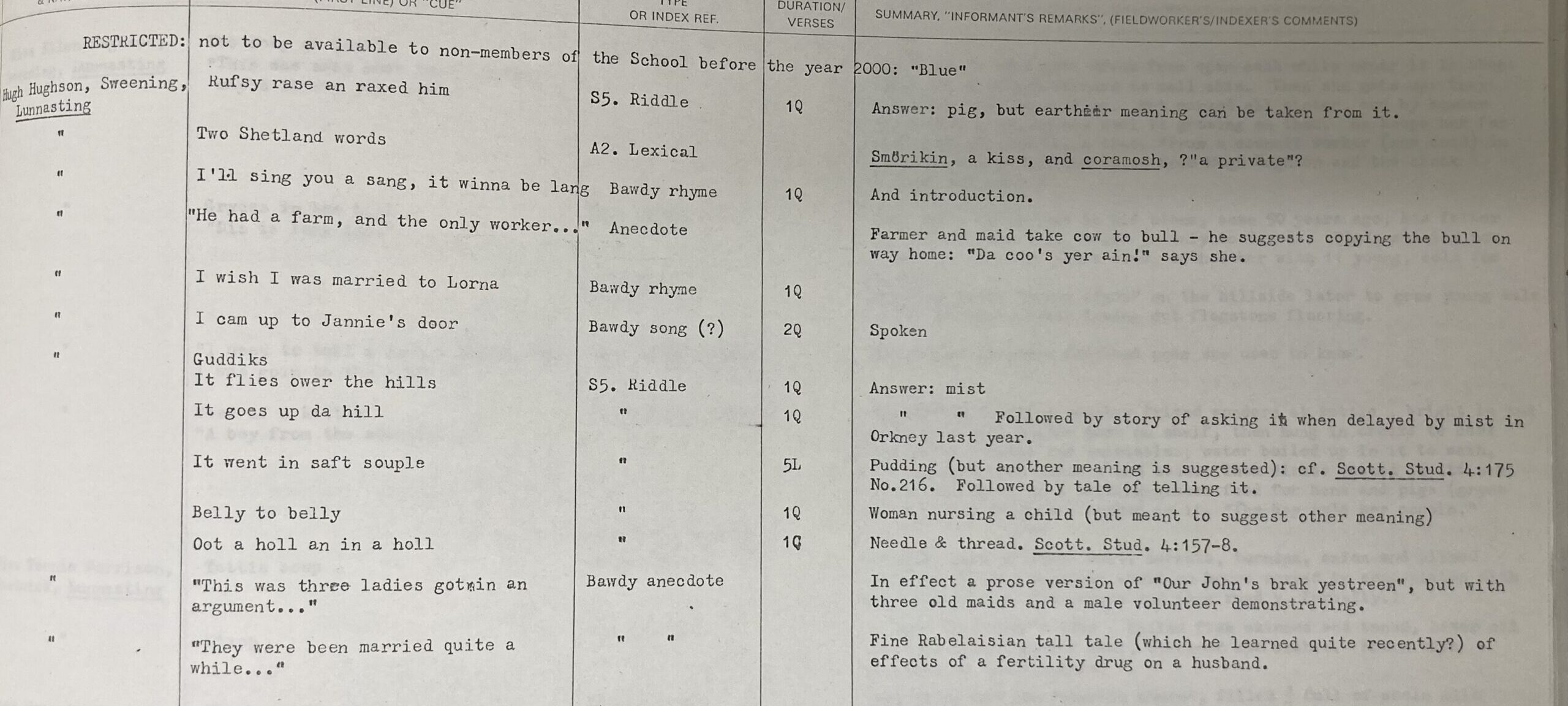

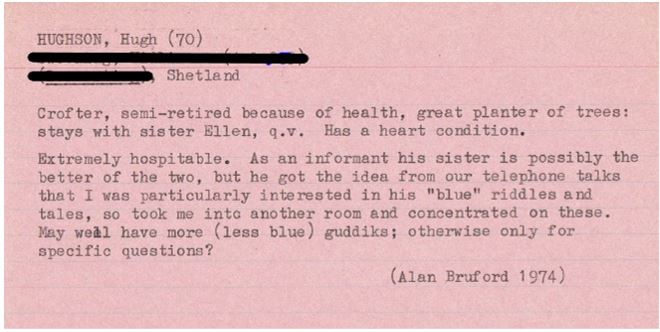

Rudeigin a’ tòiseachadh le à, rudeigin, dà litir le ceann suas, agus rudeigin eile. Ge be ciamar a thionndaidh mi e, cha robh dad a’ bualadh orm. Dh’fheuch mi an uair sin an sgeulachd a lorg ann an tùsan eile, air teans gun deach a chur ann an clò-bhualadh ’s gun robh lethbhreac nas soilleir acasan. Cha d’fhuair mi lorg air an tionndadh Ghàidhlig ach thachair gun deach an tionndadh Beurla fhoillseachadh agus bha sin ’na chuideachadh mòr dhomh. ’S e a’ Bheurla a leanas a chur Alan Bruford air an earrann seo:

We will kill the king’s graceful black palfrey, and leave it on the landing.

Palfrey? Each? Bha mi air na sgrìobh MacGilleBhàin air dhìochuimhneachadh agus cha robh à?ll/bb/bh/tl/th/??? fhathast a’ dèanamh ciall sam bith. Cha robh dad a’ nochdadh sna tùsan àbhaisteach fo palfrey. Nuair nach bi slighe eile agam, feuchaidh mi eDil gu tric, car mar oidhirp dheireannach – agus nochd na leanas air an sgrìn:

falafraigh f. (OF palefrei) a palfrey: falafraigh alafraigh IGT, Decl. § 13 . alafraidh ‘na héruim, ex. 639 . inghean … ┐ falabhraigh uaine fúithe, Each. Iol. 37.26 . g s. Inghean na Falabhrach Uaine, 38.4 . ar édach h’alafraidhe, IGT, Decl. ex. 640 . .xx. falafraidh, Fier. 111 . pl. tuc eich ┐ falafracha [sic leg.] dó, AU 1516 . an ḟalartha ghorm `the blue Ambler’ GJ vii 90 ff .

Agus mar chlach às an adhar, bha an dà chuid fhios agam dè bha san sgeulachd seo (àllaire) agus dè bha am facal fàlaire a’ ciallachadh agus nòisean carson a bha e a’ dol eadar fada agus goirid (a bharrachd air folk etymologies mar fàl). ’S e am badan de chonsain am meadhan an fhacail palfrey a bu choireach. Cha robh -lfr- nàdarra sa Ghaeilge no sa Ghàidhlig agus stob iad fuaimreag eile a-steach an toiseach: falfr– > falafr-. Mar a thachras ann an Gàidhlig an-diugh fhathast ann am faclan aig a bheil fuaimreag-chuideachaidh (mar eisimpleir falmadair /faLamədɪrʲ/). ’S e an rud inntinneach a th’ aig an fhuaimreag-chuideachaidh gu bheil e air leth làidir agus a’ tarraing beum air falbh on chiad lide agus ma dh’fhaighnicheas tu de dhaoine aig a bheil Gàidhlig o thùs, chan urrainn dhaibh a ràdh le cinnt an e fuaimreag fhada, leth-fhada, no ghoirid a th’ ann. Ar leam gun robh làmh aig an -f- ud a bharrachd is e a’ crìonadh air falbh agus dh’fhàg sin facal againn aig an robh fuaimreagan caran às an àbhaist. Tachraidh rudan mar sin uaireannan, mar eisimpleir, tha calpa /kaLabə/ car às an àbhaist oir chan fhaighear an fhuaimreag-chuideachaidh le -lp- a ghnàth ach ’s e colbtha a bh’ ann o shean, le fuaimreag-chuideachaidh ach fo bhuaidh -th- dh’fhàs am b ’na p.

A thaobh na cèille, ’s e each air leth luachmhor a bh’ ann am palfrey o shean. Bha iad comasach air ceum rèidh ris an canar ambling sa Bheurla, falaireachd, agus rachadh na h-eich seo astar fada ’s iad ri falaireachd. Cha chreid mi gun robh e riamh a’ ciallachadh brood mare gu sònraichte ach gun robh luchd nam faclairean a’ dol claon beagan leis gur e facal boireann a th’ ann am falaire. Ach ma dh’fhaoidte gun robhar deònach orra mar brood mares cuideachd… ma bha iad cho luachmhor, ’s e each mar sin a bhiodh tu ag iarraidh airson searraich a thoirt dhut, nach biodh? Co-dhiù no co-dheth, air a’ char as lugha, tha cinnt agam a-nis dè seòrsa each a th’ ann!

Cha chreid mi gu bheil fuasgladh glan ann a thaobh litreachaidh an fhacail seo. ’S ann goirid a tha e san Fhaclair Bheag a-nis oir, mar is trice, glèidhidh a’ Ghàidhlig feadhainn fhada ’s ghoirid sa chiad lide agus ’s ann goirid a tha e ann am palfrey. Ach facal inntinneach gun teagamh, cothrom tràchdais do chuideigin is dòcha a tha dèidheil air eich agus fòn-eòlas – ach a-nochd, òlaidh mi slàinte Lady Evelyn, ’s bochd nach robh na cothroman aice-se a bhiodh aice an-diugh ann an saoghal an rannsachaidh, ach ’s math gun robh i ann!

Mìcheal Bauer, cuidiche rannsachaidh