Dark Fleets and Ghost Ships: Rethinking North Korean Rights to the Sea

Dr Robert Winstanley-Chesters

2020 was a difficult year for global mobilities, however seemingly uncontrolled mobile energies were at play at sea. A particularly widely spread academic article from July 2020 focused on Chinese “Dark Fleets” of fishing boats, which had come to dominate many of the fishing grounds once important to North Korea, whose own fleet was much reduced due to Covid19 related restrictions (see footnote). Later in the year the “Dark Fleets” were reported just outside the Exclusive Economic Zone of Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands, and further reports suggested that they had created ecological pressures off West Africa.

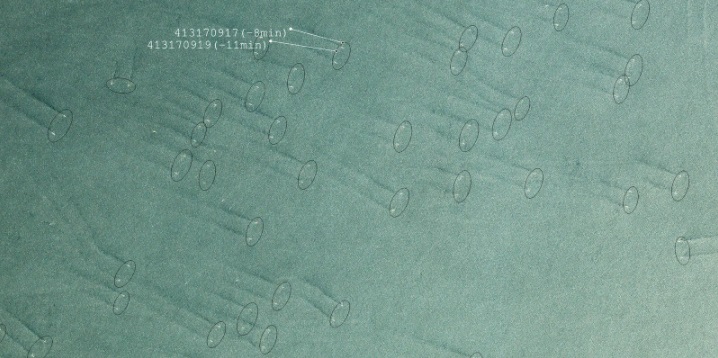

Chinese boats in North Korean waters (Park, J. et al. (2020) ‘Illuminating dark fishing fleets in North Korea’, Science Advances, 6(30), pp. 1-7. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb1197. Image derived from Planet)

Such masses of Chinese boats are of course “Dark” in many ways in global discourse. Dark in the literal sense, that they are generally invisible to the normal monitoring technologies which are so important to contemporary global fishing (they switch their AIS transponders off or do not have them fitted). But Dark in the conceptual sense, well outlined by David Shim, nefarious, illicit, and evil in intent, another long arm of the People’s Republic of China’s insatiable, ruthless desire for resource extraction. These “Dark Fleets” are highly visible given their size, and provocative given their avoidance of global monitoring systems, but not really unique in their ecological impact. Industrial fishing since the 1950s has seen a global developmental and technological arms race that has stripped the oceans of life and abundance. We have fished down the trophic levels and exploited species such as krill that would never previously been considered worth catching. Deep sea trawling has also devastated the topography of the deep ocean, transforming sea floors across the planet into flat, featureless deserts, marked by the drag lines of trawler gear.

The brazen masses of Chinese boats interestingly have displaced the North Korean “Ghost Ships,” forlorn, old fashioned, decrepit boats which washed up hundreds of times on the coasts of northern Japan, and the Russian Federation, sometimes with cargoes of deceased North Koreans. These macabre vessels, once almost as visible in the media as the Chinese from 2020, were themselves offspring of poaching fleets in the East Sea/Sea of Japan exploiting rainbow squid populations around the Yamato Bank which competed with far more technologically advanced Japanese squid boats. The boats were widely regarded as symptomatic of the heartless impulses of North Korean autocracy, men pressured to sea without support to extract value from the watery commons for faceless institutional elites.

A North Korean “ghost ship” (Kyodo News via AP Images)

What is really missing from writing and analysis around these stories of extraction and exploitation is any critical eye on the language and framing of North Korea’s rights to the sea in the first place. Whether the restriction of those rights generates any of the pressures which spurred the appearance of either the “Ghost Ships” and their human cost, and curtail potential collaboration with North Korea on maritime conservation, or the more recent “Dark Fleets,” that impact so heavily on already fragile maritime ecologies is also not considered. Much has been written on the ethical propriety of the current North Korea sanctions regime, especially by Hazel Smith and Haeyoung Kim. There is of course huge concern about North Korea’s monetization of potential maritime resources, and what that might mean for its military capacity and capability. However there is little consideration of the appropriateness of UNSC2371 (Clause 9)’s prohibition on the sale of fish, shellfish, molluscs and marine invertebrates (surely the only time in history Sea Cucumbers have become sanctioned items), nor UNSC2397 (Clause 6)’s further curtailing and restriction of North Korea’s ability to sell the rights to fish in its own sovereign waters. Whelks will never be dual use in the sense used by the drafters of sanctions, Pollack can never be anything other than food, and food stuffs are traditionally exempt from sanctions regimes, as to restrict or prohibit them would have detrimental impacts on civilian health. Yet writing on North Korean and Chinese fishing in North Korea’s own waters regularly declares any activity, uncritically to be “illegal” or “Dark.” While “Ghost Ships” may not currently set out from Chongjin as they did prior to 2020, researchers and analysts are haunted it seems by unlikely and questionable spectres of their own unreflective creation. This author suggests, when the pandemic recedes and fishers again head out to sea from North Korea’s coasts, those interested critically reconsider language and framing on Pyongyang’s rights to the water, consider coastal communities, and privilege ecology rather than security.

Chinese boats off Ulleung-do (2016, Global Fishing Watch, reprinted by SCMP)

Footnote: The details of which have been covered extensively by NK News and other North Korea focused outlets, especially the return to the sea in 2021 of some of North Korea’s shipping capacity, see as an example Min Chao Choy “North Korean Ships Return to Sea After a Quiet Covid19 Winter”, NK News Pro, February 22nd, 2021.

Author biography

Robert Winstanley-Chesters is a geographer, Lecturer at University of Leeds and Bath Spa University and Member of Wolfson College, Oxford, as well as the Managing Editor of the European Journal of Korean Studies. He is author of “Environment, Politics and Ideology in North Korea” (Lexington, 2014), “Vibrant Matters(s): Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours” (Springer, 2019) and “New Goddess of Mount Paektu: Myth and Transformation in North Korean Landscape” (Black Halo/Amazon KDP 2020). Robert is currently researching North Korean necro-mobilities and other difficult or unwelcome bodies and materials in Korean/East Asian historical geography.

Recent comments