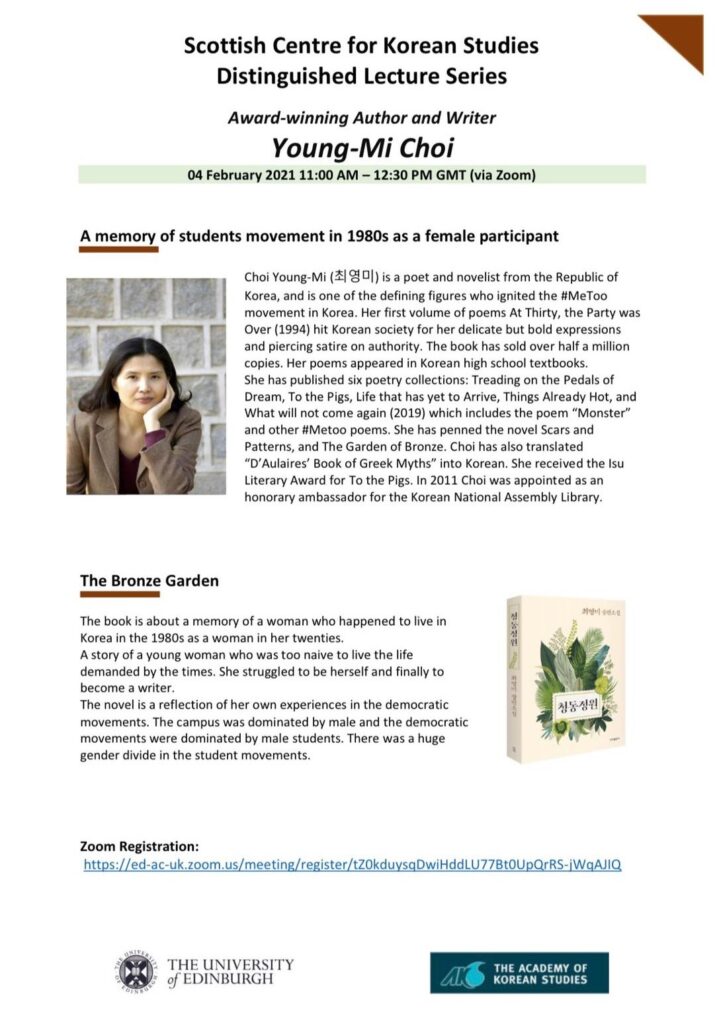

Young-Mi Choi

After reading The Bronze Garden by Young-Mi Choi

Youngmi Kim*

In the middle of endless deadlines and huge workload at the university, I really thought I could not afford any time to read a novel. But I had to make time for it, and I started to read from midnight until the dawn for a few days. On the second day in the middle of night reading two third of the book I had to have a break and sipped a wee dram of whisky to let the shock and sorrow flow down on my stomach. Would this be a shock and rage over the history that I thought I knew enough about student activists’ lives and the democratisation movement in the 1980s? There are lots of stories of student activists and some became famous politicians later on.

But we so rarely know about the lives of female activists during authoritarian times. The book tells stories of verbal abuse, sexual harassment, pervasive misogyny, domestic violence, inequality of women. It reveals the real uncomfortable ugly part of life during the time of the glorious democratisation movement. It vividly illustrates the uncomfortable, upsetting daily lives of females who had to swallow and accept a pervasive culture or perception about women in 1980s in an objective manner. This is a sorrowful story. Very upsetting.

The story is somewhat connected to what is happening now with the MeToo movement in Korea. Many well-known public figures have stepped down from their position, have gone through trials and have been sentenced. Some have taken their lives. And yet in many cases there are victims but no offenders. Or perhaps this is understood as a culture in which some behaviours were regarded by some as acceptable then and we only see victims and offenders are mostly excused by the prevailing perception, and silences, of the majority. While many agree society should change but they would say not now, not this way.

The story also reminds me of the very famous novel, Kim Ji-young born in 1982 which has been displayed in the major bookstores across the UK last summer in 2020. The book was also used as a reading material for my course “Unwritten Korea: Understanding Korean society and culture through contemporary arts and films” here at University of Edinburgh. While Kim Ji-young born in 1982 illustrates female lives in 2000s as being heavily affected by neo-liberal policies, The Bronze Garden is about a woman in the 80s who participated in the fight against the authoritarian government to achieve democracy. While South Korea’s economy has reached the top 10 (or top 9 January 2021) in terms of size, and its democracy has consolidated, many problems remain. Misogyny, gender inequality and old values, behaviours, and expectations imposing women to sacrifice, this patriarchal society did not change much. In that sense 30 years on, Korean society has not changed that much. There are many touching sentences in the book. One of the sentences remains most to me was being divorced was like un-erasable mural to move on for a new life.

I hope this novel is also translated in foreign languages and read broadly.

*Youngmi Kim is senior lecturer at Department of Asian Studies, University of Edinburgh, Director of Scottish Centre for Korean Studies.

Q&A with Young-Mi Choi

In the novel The Bronze Garden, how do you see Erin’s transition from student to writer? What would be the biggest fuel that drove this transition?

After graduating from college and after divorcing from Donghyuk (동혁), Erin regained her voice. She began to rebuild her ego, which had been suppressed by male comrades, by male seniors and by her husband.

He controlled Erin and she could not speak freely. As a literature girl, she loved to talk, but she had to live in silence. At campus the male seniors used to force her to shut up…. She lost her way for a long time. Then after divorcing from Donghyuk, she regained her voice. Still she needs support from girl friends and female seniors. As time passed, she became independent.

She became a writer in the process of finding her voice, which had been suppressed by the era of 1980’s and by the male activists, especially by her husband. Divorce is the biggest fuel that drove this transition.

When Erin went to the university campus, she saw a message written in the snow. ‘자유 민주주의 만세 (For liberal democracy)’ What messages do you think should be written in the snow in today’s universities?

I’d like to say that… Truth will set you free. or that

Only when I change myself, will the world change.

Reading through Erin’s experience and observing my family’s experience as women in 1980s, my experience as a woman in South Korean society was comparatively easier. However, inequality between men and women still exist, and many people face everyday sexism in society. What’s the biggest challenge as a female writer in current South Korean society?

The biggest challenge as a female writer is money and freedom. Independent female writers in Korea have little chance to survive. It is practically difficult for a female writer to build her career without support from powerful male editors (of major literary magazines) and male critics.

It is difficult to publish her book and more difficult to sell her book without support from editors and critics (of the literary power house like Changbi, Munsi), whom readers trust. The mainstream media reporters tend to write friendly reviews especially on the books from large, rich and famous publishers.

Korean book-stores take money from certain publishers and display their books in popular places. So the readers have no choice but to buy those books.

Recently I wrote an essay for a magazine, criticizing the suicide of the former Seoul mayor who had been accused of sexually harassing his female secretary. After the article was published, more than 4,000 comments were posted in a day, most of them denouncing me. I do not feel comfortable when I write about politics and feminism in Korea. I need more freedom.

If Erin were to go to university in 2021, what kind of life would Erin have? For instance, what would she be wearing, and what would be her life path?

First of all, she may quit smoking.

She loves beautiful things. She loves colours.

She may wear colourful clothes and fancy dresses.

In the novel Bronze Garden, Erin rejects her father’s advice to go to Greece and study Western history with government scholarship. She said to herself: Leaving Korea now would be betraying my comrades who are fighting against military dictatorship, so she missed the opportunity to study in Europe.

If Erin were to go to university in 2021, She would not hesitate to study abroad. She would master at least two foreign languages, and become a professor in history or a diplomat. I have no doubt that she would marry a European, and she would become a cosmopolitan with a global sense.

Could you expand on the interconnectivity between masculinity and the Korean family structure?

Korea is a very patriarchal society. When Erin entered college, she was forced to call her male senior as ‘형’ (‘Hyeong’), even though she was a woman.

In Korea ‘형’ (‘Hyeong’) is used among males. Younger males are supposed to call elder ones ‘형’ (‘Hyeong’) (brother) and between female siblings younger sister call her elder sister ‘언니’ (‘Unni’).

She thought it was awkward and funny non sense.

Why do I have to call a male student who is older than me as ‘형’ (‘Hyeong’)? He is not my biological brother. Even if he is my brother, I am a woman, so the man who was born earlier than me is not my ‘형’ (‘Hyeong’) but my ‘오빠’ (‘Oppa’).

The uni. campus in Korea was like a clan society where everyone was relatives of each other. Suddenly she had hundreds of sisters and hundreds of brothers. She could not adapt to the male dominated university culture. She could not get used to the male dominated student movement with a clear hierarchy.

I am interested in the ongoing influence of Confucianism on gender in South Korea. Could you speak a little more about the extent to which you saw Confucian norms manifest during the student movement, and do you think there is a relationship between South Korea’s Confucian history and attitudes towards women today?

Let me simplify Confucian norms of behavior which manifested during the student movement.

(1) The juniors should obey the seniors

(2) women should obey men.

The seniors often suppressed the juniors.

The senior male students suppressed the junior female students.

The junior students must follow their senior students’ opinions without question.

The seniors did teach the juniors and raised them as fighters. The uni. culture based on the year of admission ‘학번’ made it easy for the senior students to control the juniors.

‘학번’ means the year when the student entered the university.

The dominance of the seniors was absolute in the student movement. It was like a military army.

In 1980’s the campus was dominated by male students and so was the pro-democracy movement. There was a huge gender divide within the student movements. Male senior students decided when to fight, when to stop fighting, and what to read.

During the demonstration, boys threw stones at the police, while girls carried stones and handed them over to the boys. Such gender-based role was not something that anyone forced us to do, but that we learned by ourselves, living as girls in the student movement.

I entered university in 1980. Female students of humanities were not able to join the “ideology circles”, student activist groups. There was women-only group as well and the female leaders put pressure on those “ideology circles” not to accept female students, saying that male seniors were trying to lure junior female students into a relationship without teaching them as fighters.

Senior female students were busy studying, fighting, and dating their boyfriends and they didn’t have enough time to look after their female juniors.

A loner like myself couldn’t know what was going on student activism. If you didn’t have a boyfriend in those ideology circles, you were easy to be marginalised and to become an outsider within the group.

People are willing to accept feminism in theory, but the Confucian morality still remains deep inside Koreans’ consciousness. The Confucian norms that women should obey men (남존여비), that Boys and girls over the age of seven should not sit together (남녀칠세부동석), still have power at the corner of Korean society.

Education that focuses on entrance exams encourages sex crimes. Because boys and girls are not allowed to have a date freely, so boys don’t know how to treat women as adults, and some of them solve their desires in a distorted way. Many Korean men don’t really know about the joy of life other than money, power and sex.

The Confucian values that demand purity only for women have encouraged the culture of sexual violence. Korean men do not respect un-married women who are not virgin.

There was and still is a widespread pre-modern Confucian culture that treated female poets as 기생 Geisha. Sexual harassment by male literati was (and is) routine in Korea.

A male poet insulted me by posting a comment titled ‘괴물과 퇴물’ (‘Monster and retired geisha’) shortly after my Me Too in 2018. To the eyes of the male poet, Choi Young-Mi in her fifties was finished as a woman and as a geisha.

That is the reality I face today in Korea.

#MeToo is not a fight between men and women, but a fight between the past and the future.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.