Culture: the poetry of Park Nohae

Longing for Fingerprints – 지문을 부른다

Park Nohae (translated by Professor An, Seon Jae (Brother Anthony MBE))

As we hunch together, plowing our way

through the falling sleet, we laugh,

saying that we’d better tell the truth

if we’re going to keep dealing with things

during working hours.

We enter the local government office.

Peeling the wrapping off the photo

of a shabby twenty-nine-year-old,

I’ve spent some six years,

buried in the Garibong-dong industrial park,

day and night, time passing,

spent in meaningless death-like labor,

and now I renew my civilian registration,

proving for once that I’m still the same citizen.

I stretch out a proud hand, blackened and rough,

with which I feed and support my family

by producing goods for export

without ever once committing a crime,

and make a fingerprint,

ah!

nothing there,

quite clearly nothing there!

Eaten away by labor,

the fingerprint which is supposed to distinguish me

from any other person has vanished,

there’s nothing left, and likewise it’s vanished from

Jeong, and Yi and Mun.

Although the policeman present gets angry,

in the course of long labor,

our fingerprints, our youth, our very existence

have all vanished away,

buried in the products exported across the sea.

After trying a few more times,

fingerprints fail to emerge and finally the girls

working in the chemical products factory burst into tears

one after another, so that all of us having no fingerprints

have no identity

and Jeong jokes

that we’ll leave no trace if we engage in burglary

but nobody feels like laughing.

All we who have no fingerprints

plunge back into the sleet falling as pellets,

in frozen silence

declaring that we are still citizens like anyone else,

go back to bury ourselves in the factory again.

longing for our fingerprints

to revive clearly,

longing for a worker’s fresh green life,

for our identity, yours and mine,

to revive again,

longing, longing

for a fresh springtime for workers,

into the sleet

with fiercely blazing yearning.

Park Nohae.

About Park Nohae

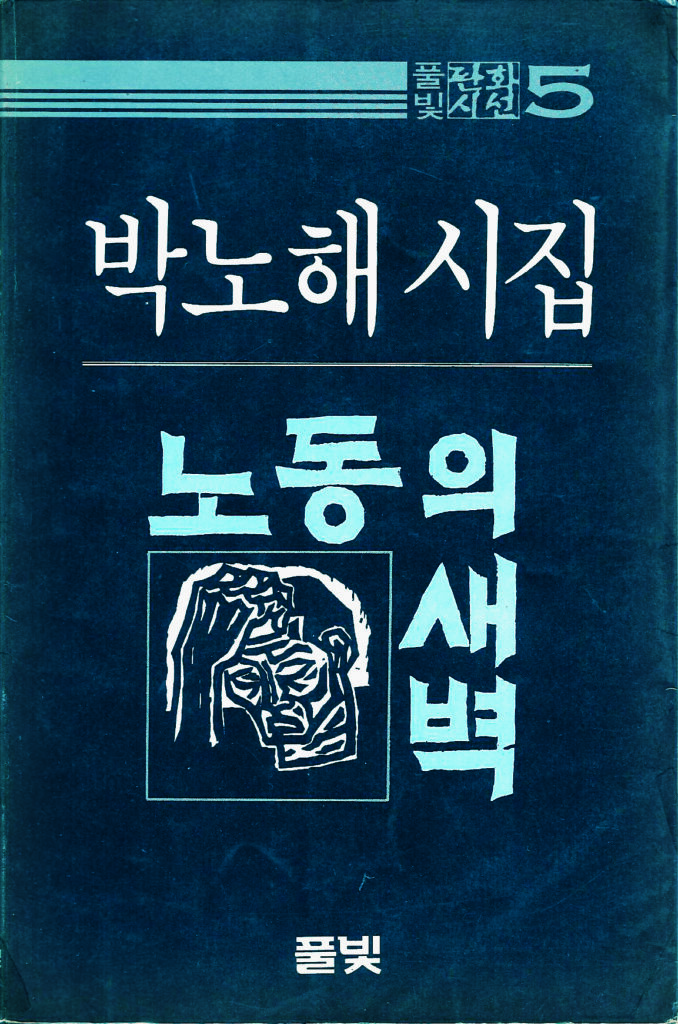

When Park Nohae published his first collection of poems, “Dawn of Labor,” in 1984, people at once understood that “Nohae” was not the poet’s real name but an abbreviation of “Nodong Haebang,” “Workers’ Liberation.” It was not until his arrest as an “enemy of the state” in 1991 that his real name and identity were known, together with the first photographs of his face. After spending three weeks being very roughly treated in an underground interrogation cell, he emerged from the van for the start of his trial smiling broadly for the benefit of the waiting journalists with their cameras. The Prosecution demanded the death penalty for advocating Socialism, the court decided that a life sentence in solitary confinement would be sufficient. By that time, “Dawn of Labor” had sold nearly a million copies.

Park Nohae had been a factory worker from the age of sixteen, gaining his high-school graduation certificate by studying at evening classes. The poems in “Dawn of Labor” are not all autobiographical in the strict sense, but express in vividly characterized voices the harsh, dehumanizing experiences of his generation of factory workers. The poet’s strong sympathy for the wounded humanity of the multitude of over-worked, under-paid, exploited laborers rang out clearly, so that some people wondered if the volume was not a collective work, composed by multiple poets hiding in a single, symbolic name. The impact of these glimpses of the helpless plight of young workers was such that some university students felt obliged to give up their studies, go to work in factories, and join the workers’ struggle.

One feature that made the collection so popular was its occasional dour humor, as in this much-loved poem. The civilian ID card carried by every Korean includes not only the photo and address but also the finger prints of each index finger. This poem evokes the many workers whose constant exposure to corrosive acids and work with abrasive substances ends up by erasing their fingerprints, to say nothing of their identity. The absence of finger prints becomes a symbol for the worker’s lack of human identity in modern, industrial society. They have no finger prints just as they have no voice, no power, no rights.

Some will ask if this is really a “poem.” It is so natural, colloquial, “unpoetic.” The poems of Park’s first collection are certainly not very “lyrical,” and they have no rhyme or patterned rhythms, being written in a kind of blank verse, like most modern Korean poetry. Clearly, the poem is designed to evoke the readers’ sympathy for those confined in the real world of the working class. Another poem in the same collection, “A Hand Grave,” works in a similar way. A worker is just looking forward to a Children’s Day outing with his family when the machine he is working on cuts off his hand. Obviously, he needs urgent treatment in a hospital, but since he is bleeding a lot, none of the wealthy guys at management level want to offer their official car to transport him, he has to go in the back of a truck. Later in the poem, he tries to find a book in a downtown bookstore outlining his rights when it comes to industrial accidents, but central Seoul is another world: “Saloon cars were lined up in front of multistory saunas, luxury cars filled the space in front of high-class saloon bars, huge department stores were packed” and nobody has time for a one-handed worker who has just been fired.

Park Nohae is a unique figure, also, because he did not stay confined in the world of the Gurdodong factories. Emerging from prison, entering into the new century, he turned his back on the Korean workers’ struggle and went outside of Korea, first to the Middle East, to serve as a “human shield” during the American invasion of Iran, and then across the world to countries suffering from war, injustice, conflicts, poverty, in South-East Asia, South America, Ethiopia, Sudan, the Middle East, transforming his poetry into the more directly accessible language of photography. With captions of a few phrases, his photos continue to draw the beholders / readers into a world of pain and compassion. Instead of Korean nationalistic particularism, Park Nohae asks us to realize that our responsibility is to the entire human family and that community in sharing is the only hope for humanity’s future. He is preparing new books, living withdrawn from urban society in a rural farming village, a poet unlike any other Korea has ever known.

For more information about Park Nohae and his poetry, please see Professor An, Seon Jae’s website.

About the translator

Professor An, Seon Jae (Brother Anthony MBE) was born in England and has lived in Korea since 1980. He is an Emeritus Professor of Sogang University and a Chair Professor at Dankook University. He has published over 50 volumes of translations of Korean poetry and fiction, most recently work by Kim Seung-Hee, Jeong Ho-Seung, Yoo Anjin.

‘Dawn of Labor’, Park Nohae’s first collection of poems.

I first heard of his poetry from the k drama “man to man” and I am trying to find out how I can get a copy in English translation of his works. Has poem “Sky” spoke to my heart. I want so much to learn more about Him and his works.