Another Korean Miracle? The Paradox of Civic Trust in the Dataveillance State in the COVID 19 Crisis

Hoon Jaung (Professor, Dept. Political Science and International Relations, Chung Ang University)

This essay was drawn from the author’s publication in Korean, “COVID 19 Crisis and Korean Dataveillance State,” in Korean Journal of Legislative Studies vol. 26(3), 2020.

When the world fell into the COVID 19 crisis in early 2020, South Korea seemed to be achieving another Asian miracle. Even without outright lockdowns and travel bans, the country effectively kept the corona virus from spiraling out of control. Korean’s early success in dealing with the corona crisis has been widely documented and acclaimed under the name K-quarantine.

Various explanations have been proposed for the success of Korea’s fight against COVID 19. The first of these, widely discussed, is the resource mobilization and implementation capacity of the state, which has grown remarkably since the era of the so-called developmental state. The second is Korean society’s ability, thanks to rapidly developed digital infrastructure, to successfully trace COVID 19 and treat patients based on effective and ubiquitous digital infrastructure. The third is the communitarian ethos and civic conformity that Korean citizens showed in times of crisis (Breen 2020, Government of the Republic of Korea 2020, Jo 2020).

This article revisits the role of the compliant attitude of citizens in relation to the three factors mentioned above. I do not claim that this line of explanation originated from orientalism in western intellectual communities. Yet I suggest that such an explanation is based on an inappropriate understanding of the relationship between Korean citizens and the state after democratization, and of civic trust among citizens. Specifically, I argue that explanations that emphasize civic conformity and communitarian trust are incongruent with the evolving pattern of Korean civic culture since democratization. These explanations are also inadequate for capturing subtle changes in the interaction between the dataveillance state and citizenship.

First, I briefly explain the concept of the dataveillance state before examining the role of Korean civic attitude and trust toward the dataveillance state during the COVID 19 crisis.

The rise of dataveillance state is not an exceptional phenomenon in Korea. This new mode of the state is quite widely observed in the transition to data capitalism in the 21st century (Zuboff 2019). Just as in the 20th century Fordist capitalism, under which the production of goods and services was central, was paired with the so-called democratic welfare state, in the 21st century it is the dataveillance state that supports data capitalism, in which the creation, extraction, and use of data form the core axis of capital activity.

The dataveillance state supports the emergence and growth of data companies such as Google, Tencent, and Naver. In this new mode the state is the main architect of the transformation to data capitalism, extracting, aggregating, and using vast amounts of data through cooperation between the state itself and leading companies. The state also demonstrates its raison d’etre by protecting the lives and property of its citizens from various threats. For instance, as various risks such as terrorist threats and climate disasters have arisen, not only authoritarian but also democratic countries have acquired abilities to collect and use a wide range of citizens’ movements by tracking data, personal identification, and biometric information. For example, the United States, which experienced anthrax attacks in 2001, began to do so in 2004 as part of the Homeland Security Presidential Directive 10. Since 2018, the White House has been leading the National Biodefense Strategy, which includes bioveillance and biocontainment, as well as collecting and tracking medical information (White House 2018).

Below, I examine the attitude and trust of Korean citizens during the COVID 19 crisis, and its relationship with the dataveillance state. Specifically, prior to the COVID 19 crisis, a number of studies have demonstrated that Korean citizens have relatively low confidence in the Korean state and in their fellow citizens. Interestingly, as the COVID 19 crisis deepens, trust among Korean citizens has risen sharply. However, while vertical trust in the state has risen, trust in fellow citizens has not increased significantly. In other words, the sharing and disseminating of crisis consciousness has been carried out vertically from the state to individual citizens. The horizontal sharing of crisis awareness between individual citizens and the accompanying emotional and ethical solidarity and sympathy did not occur, however.

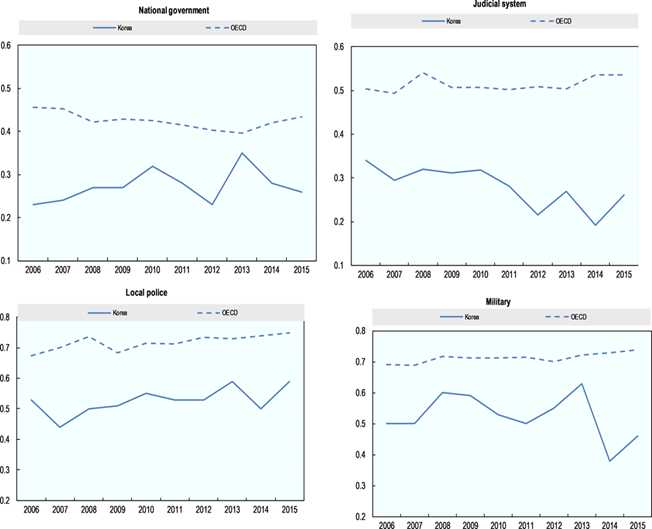

First of all, the view of Korean citizens as compliant and communal citizens contradicts the vast empirical analysis built up over the past decade. OECD data show that during the period from 2006 to 2015, Korean citizens’ confidence in major national institutions such as the central government, the judicial system, the police, and the military was consistently and significantly lower than the OECD average. Confidence in the government appears to be steady at a level of 0.2-.03 on a scale of 1 to 0. This is relatively low compared to the average confidence level of the OECD countries which hovers around the 0.4-0.5 level.

Figure 1. Civic Trust in Governmental Institutions in Korea (2006-2015)

Source: OECD and Korea Development Institute (2018) ‘Trust in government in Korea: a puzzle‘ in ‘Understanding the Drivers of Trust in Government Institutions in Korea’. Accessed on May 30, 2021.

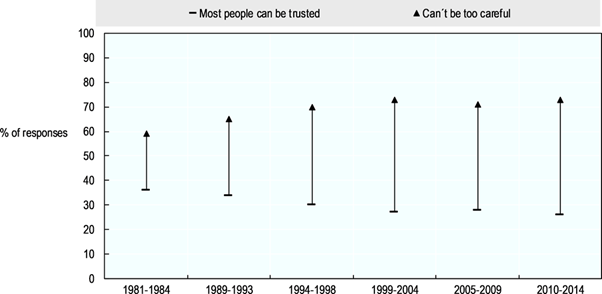

Meanwhile, studies have demonstrated that social trust among citizens, which forms the basis of communitarianism, is not high among citizens of Korea. The World Value Survey has measured mutual trust among citizens in dozens of countries around the world over a long period of time, and since the late 1980s when Korean democratization began, mutual trust among citizens has gradually declined. The proportion of respondents in Korea who answered “I can trust most people” declined gradually and steadily around 35% in the first half of the 1980s (1981-1984), approximately 30% during the most recent survey period, 2010-2014.

Figure 2. Changes in Civic Trust in Korea (1981-2014)

Source: OECD and Korea Development Institute (2018) ‘Trust in government in Korea: a puzzle‘ in ‘Understanding the Drivers of Trust in Government Institutions in Korea’. Accessed on May 30, 2021.

At the same time, the rate of respondents saying, “It is not too much to be very careful with other people,” has steadily increased since the 1980s. In the 1980s (1981-1984), 60% of respondents said that they had to be very careful when dealing with others, and the level of lack of trust increased steadily thereafter. Over 70% of respondents during the 2010-2014 survey period replied that they should be very careful.

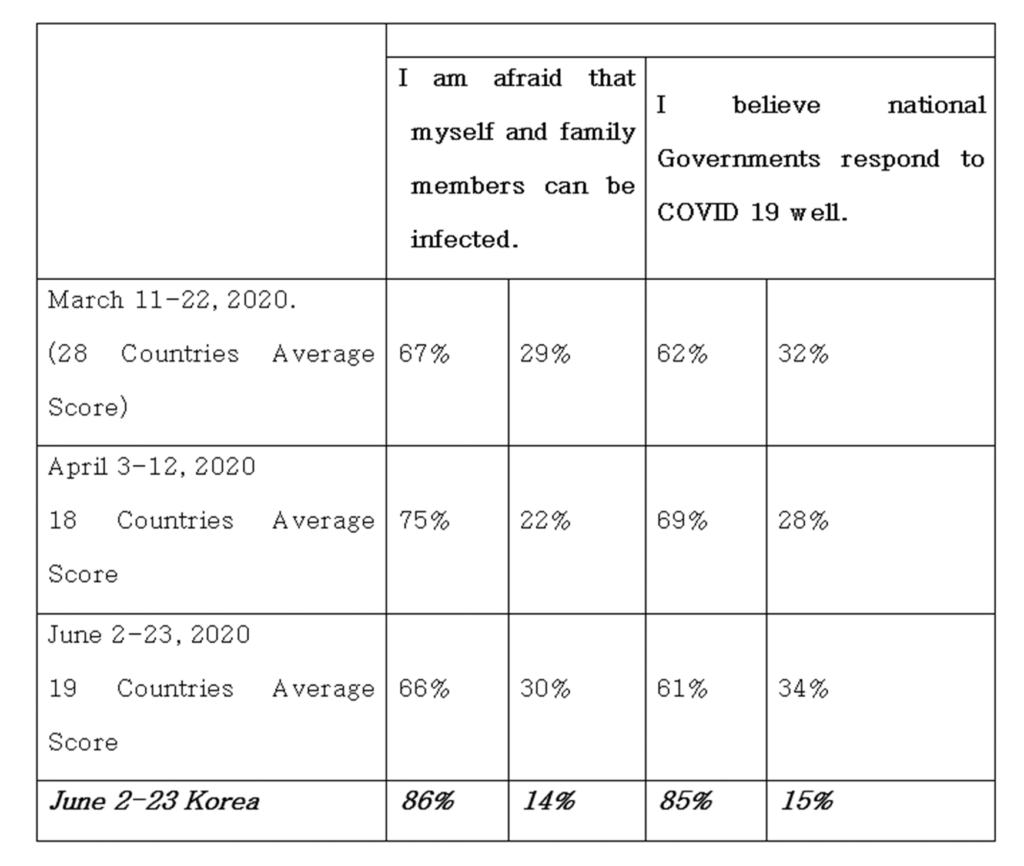

This low trust between the state agencies and Korean citizens began to change significantly after the COVID 19 crisis. First, during the corona crisis, citizens have evaluated the country’s response to the crisis very positively, comparatively speaking. Table 1 presents Gallup’s survey of citizens of 19 countries on their evaluation of government responses to the pandemic and their perceptions of COVID 19 risk. The survey shows that Korean citizens overwhelmingly agreed that the state responded well to the COVID 19 crisis, even given the usual low trust in government agencies. In the June 2020 survey, 85% of citizens answered that the government was responding well, while only 15% disagreed. It is in marked contrast to the pattern whereby on average of only 61% of citizens of the 19 countries surveyed evaluated the government’s response positively and 34% negatively.

Table 1. Evaluation of National Governments’ Responses to COVID 19 Crisis: A Cross-National Survey by Gallup

Source: Gallup Korea. Gallup Report. June 23, 2020.

This pattern is also confirmed in an analysis of a comparative survey by the Pew Research Center in the United States in August 2020. As Table 2 below shows, 86% of Korean citizens said that the government was responding appropriately to the corona crisis, while only 14% disagreed. This is higher than the 73% average positive evaluation of the 14 countries surveyed.

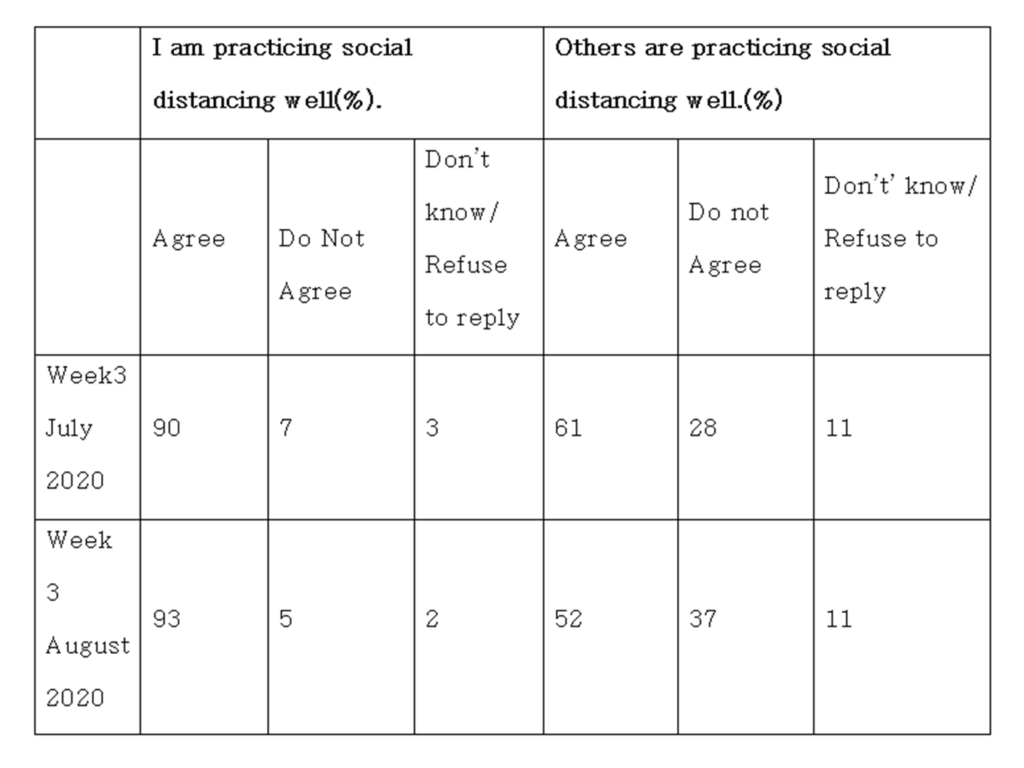

Second, despite the high positive evaluation of the country’s response to the coronavirus, Korean citizens do not give similar high evaluations to their fellow citizens. According to a survey conducted by Gallup Korea in August 2020, citizens almost overwhelmingly responded that they are themselves practicing social distancing well (93%), while other people are practicing social distancing to only a moderate extent (52%).

Table 2. Korean Citizens’ Evaluation of Social Distancing During COVID 19 Crisis

Source: Gallup Korea, Daily Opinion. August 21, 2020.

The fact that Korean citizens positively evaluated the role of the state in responding to the corona crisis, but not the role of fellow citizens, cannot be explained by the concept of Asian communitarianism that has widely been cited by the Western academic community and journalists. While citizens did actively observe the obligations imposed by political power of the dataveillance state, but the degree of solidarity and sympathy among the members within civil society is not sufficient to speak of Asian or Korean communitarianism.

We may call this paradoxical pattern in responding to the COVID 19 health crisis in Korea a state-led extrusion governance model (Song Gyeong-jae, Jang Woo-young, Jo In-ho 2018). The state has effectively carried out bio-security governance that has successfully blocked the spread of the corona infection by organizing and mobilizing private and government networks, extracting data, and imposing roles on citizens.

Whereas there has been ample discussion about the role of civic trust among citizens during the health crisis, active community solidarity and empathy among citizens, as well as participation in policies, have not yet occurred in manifest ways. In fact, several have criticized that there have been implicit social discrimination against infected persons (Kim Ji-ho 2020). Some have also raised the issue of human rights and privacy violation in the course of the Korean CDC’s tracing and treating COVID 19 infected people (Seo 2021).

In accordance with the recommendations of the Human Rights Commission, the Korean CDC (Center for Disease Control) made it possible to disclose only essential routes of movement, such as the path of travel of the confirmed persons and the places of visits (Hu, Yun-Jung 2020, 36).

In sum, it can be said that the dataveillance state of Korea has succeeded in obtaining broad consent from citizens in recognizing and responding to health crises, extracting data, and enforcing civic behavior in compliance with quarantine guidelines. However, its achievement did not go beyond the passive consent of citizens to secure bio-safety from health crisis. We still lack a full understanding of the meaning and scope of the civic autonomy and subjectivity of individual citizens in the health crisis in Korea. For now, we can only say that the relationship between the Korean dataveillance state and citizens worked in the state-led extruded governance model during the COVID 19 crisis.

References

Breen. Michael. 2020. “What’s fueling Korea’s coronavirus success and relapse” Politico (May 15)

Government of the Republic of Korea. 2020. “Flattening the Curve on Covid 19-How Korea Responded to a Pandemic using ICT” http://overseas.mofa.go.kr/us-Houstongon/brd/m5573/vew.do?seq=759765.

Hu, Yun-Jung 2020. CORONA Report. Seoul: DongAsia Press.

Jo, Eun A. 2020. “A Democratic Response to Coronavirus: Lessons from South Korea,” The Diplomat March 2020

Kim, Ji-Ho. 2020 I have got COVID 19: Between Anxiety and Hatred. Seoul: The Nan Press. (in Korean)

Seo, Chang-Rok. 2021. I have got infected. Seoul: Moonhakdongnae. (in Korean)

Song, Gyeong Jae, Jang Woo-Young and Jo In-ho. 2018. “Exploring possibilities and Issues of Big Data Governance in Korea,” Social Theory vol.1. 153-186. (in Korean)

Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. New York: Public Affairs.

Author biography

Hoon Jaung (장훈) is a professor at the department of Political Science and International Relations at Chung Ang University and a columnist for Joongang Ilbo in South Korea.

Recent comments