Engaging the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

Dr. Jim Hoare*

The election of Joe Biden as US president has once again brought the question of engaging with the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea – North Korea) to the fore. It is doubtful, of course, that the DPRK will be very high on Biden’s list of urgent tasks but sooner or later he will have to address the issue. Already there are plenty of people ready to give advice. Some are for a tough line, claiming that there are no benefits and high costs in any attempt at a close relationship with the DPRK. Others argue that, while there are costs, there are also benefits, not least in preserving peace on the Korean Peninsula.

My own view, which dates from my time in Seoul in the early 1980s, is that whatever costs there have been over the years associated with engagement, they have been far outweighed by the benefits of avoiding another all-out conflict like the Korean War, which started seventy years ago, and followed the division of the peninsula in 1945. In 1945, of course, a permanent division of the peninsula into two separate states was not intended. Actions, however, often have unintended consequences, and so it proved in Korea. The war was one form of engagement that settled nothing except the perpetuation and intensification of the division. The 1953 Armistice Agreement, which halted the fighting, was another. The armistice is often derided and of course it was breached by both sides from the start. But it has held and despite periods of high tension, has continued to do so. Even though the DPRK has regularly announced that it will no longer honour the agreement, and high-level meetings have stopped after the appointment of a ROK general to head them on the United Nations’ Command side, the apparatus still functions and the DPRK abides by the rules.

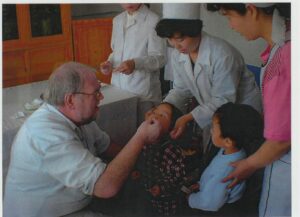

Dr. Hoare is pictured working as part of a UNICEF and diplomatic team helping with a polio vaccination campaign in Haeju, North Korea (Autumn, 2001).

There is no doubt that engagement with the DPRK is not easy. The country itself seems to do little to encourage it. Outsiders and their intentions are viewed with suspicion; fellow Koreans are no exception. Revelations from the archives after the end of the Soviet Union, showed a similar suspicion of those countries that were seen as friendly. This of course was particularly so during the Sino-Soviet dispute from the late 1950s, but this distrust had been there before. Yet at the same time, the DPRK showed itself willing to engage in certain areas. North Korean students were sent to study abroad. They included nuclear scientists, sent to the Soviet Union, but also medical students and others. Some seem to have studied in places such as Malta. Students from other communist countries could and did study in the DPRK. They included not only language students of whom there were many, but also economists and political scientists. In China in the 1980s, there were many cadres who had studied such subjects, and there were also African and Asian students taking degrees in the DPRK, for example, in economics and medicine (How useful a DPRK medical degree was, with its high political content, is another matter). In Pyongyang from 2001-02, many of my fellow diplomats had learnt their Korean at North Korean universities. Indeed, several had been at Kim Il Sung University when Kim Jong Il was a student. After the end of the Soviet Union and as the DPRK came out of the famine years of the 1990s, its students once again went abroad to a variety of countries including Australia, France, and Switzerland – there were even a few in the UK.

And what of the ROK and engagement? Sometimes one reads that engagement was only tried under the “left-wing” administrations of Presidents Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun between 1998 and 2008, and that it failed to achieve anything. This is bad history. At least since President Park Chung-hee’s decision in 1971-72, to abandon the hitherto restrictive attitude towards the DPRK, successive ROK presidents have wanted engagement. Even Park’s successor, President Chun Doo-hwan, in spite of the attempt to kill him in Yangon (Rangoon) in 1983, continued to try to improve North-South relations. Thus, in August 1984, less than a year after the incident in Yangon, when the North offered assistance after Seoul and Kyonggi province were badly hit by floods, Chun accepted. (For an interesting account, see here.) But Chun was soon preoccupied with other matters and the initiative withered. Under Roh Tae-woo, Chun’s successor, engagement again featured, leading to a whole series of agreements which were reached in 1990-91. Alas! They were never implemented. Roh gave up, turning his attention to Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union and China, with more success. Kim Young-sam was prepared to meet Kim Il Sung but when the latter died just before the planned summit, he refused to send condolences and contacts ceased.

An EU tractor, given to a potato research institute (Summer, 2002).

The difference under Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun was that they stuck to the policy of engagement, riding out setbacks and making it clear that they were in for a long haul. I think it was a successful policy but it failed because of the change of administrations in the US. President Clinton supported such a policy, President George W. Bush did not, even though it was his father, President George H. W. Bush, who had authorized the first tentative talks between the US and the DPRK in 1988. Of course engagement cost money but there were benefits for the ROK as well as costs. The two Koreas got to know each other in a way that would have seemed impossible from the 1950s to the 1990s. Ups and downs there were – divisions have gone deep – but they were able to work together. And there were important developments for both. Thus, the DPRK gained a degree of international acceptance, expanding its diplomatic relations and finding it could tap into international aid. For the ROK, there were opportunities – albeit limited ones – to visit the North both for business and for tourism. An ROK ambassador in London told me about 2003 that on any given day, there were several thousand South Koreans in the North – and when I was there, I met some of them. A Catholic priest saying mass in a Pyongyang church, officials and business people in the hotels and restaurants – I was even interviewed in a hotel shop by a KBS TV crew!

But engagement is not about these relatively small things. It is the means of dealing with the DPRK. The West wants the DPRK to do certain things – give up nuclear weapons, improve its human rights record etc. The way to do that is neither by isolation nor by megaphone diplomacy but by engagement.

*Dr. Jim Hoare was the first British representative in Pyongyang, where he established the British Embassy in 2001-02.

Recent comments