Anna Grasso (UK Team and Website data analysis)

Gary R Bunt (UK Team and Website data analysis)

Dorota Wójciak (Poland Team)

This short piece was written using the Ramadan collection, which comprises archived webpages and articles from online organizations and Muslim media platforms across the five countries involved in the DigitIslam project during the month of Ramadan. These pages contain discussions, announcements, and articles about Ramadan, including religious guidance, community preparations, and debates such as the moonsighting issue.

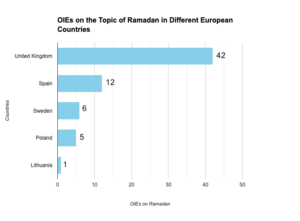

The content was mainly collected between March and April 2024, with a few additions in November and December 2024. The objective was to capture a global perspective from Muslim websites in the project’s countries (United Kingdom, Spain, Sweden, Poland, and Lithuania). Naturally, there was a significant discrepancy between the content gathered from one country to another.

Graph generated using Gemini based on DigitIslam dataset

Moreover, despite the content being mostly from 2024, we also chose to include some older and newer materials. The older content, such as the case of Liga Muzułmańska w RP (Muslim League in Poland) from 2021, as well as a 2020 study by the British Board of Scholars & Imams (UK) on the longstanding debate on moonsighting issues – especially the timings of Ramadan’s conclusion and Eid ul-Fitr – pointed to websites that had produced less content. On the other hand, during our revision of websites in November and December 2024, we noticed that some organizations and media platforms (such as the Inclusive Mosque Initiative and Eman Channel) had already started posting information and advertisements for Ramadan 2025.

An initial analysis and comparison of the archived content revealed various transnational parallels between the materials. For instance, most of the posts during this period focused on announcing the official dates for the start and end of Ramadan. Moreover, many pages centred on humanitarian crises like the ongoing conflict in Gaza, urging solidarity, political activism, and charitable giving to support vulnerable communities.

We chose to look closely at the pages that highlight the practice of “sharing” Ramadan as an opportunity for building bridges and educating the public.1 This is primarily done by organising community events such as public and interfaith Iftars where the Muslim organisations and mosques invite non-Muslims to share a meal. In this context, websites are used to report on these events and provide photos. Additionally, webpages can serve as a practical tool for pedagogical and de-demonisation purposes, explaining the meaning of Ramadan and comparing it to fasting traditions in other faiths like Christianity and Judaism.

Public and Interfaith Iftars

Iftar is a symbolic moment during the month of Ramadan, occurring in the evening when Muslims break their fast. In Muslim-majority countries, it is often celebrated with family, friends, or the community. In countries where Muslims are a well-established minority (as in the case of the United Kingdom and Spain), Muslim organisations frequently host events to introduce and include non-Muslim individuals and organisations in this communal experience. In countries such as Poland, where the Muslim population is small and geographically dispersed, Iftars hosted by mosques play a crucial role in strengthening communal bonds among Muslims. Yet, even in this highly minoritarian context, some organisations still manage to arrange public and interfaith events.

We find traces of such practices in the digital realm. For instance, large online associations establish specific initiatives with dedicated websites (as seen with those from the United Kingdom) or report on such events in their organisation’s news sections (as seen on websites from Spain and Poland).

Examples from the UK

Three examples from the UK are Ramadan Tent, Taste Ramadan, and The Big Iftar.

Ramadan Tent is a UK-based charity that organizes various events during Ramadan to promote cultural understanding and community engagement. Founded by SOAS University students in 2013, it has gained significant popularity for its “Open Iftar” initiative. For its 2024 edition, various events were held across the UK in iconic locations like football stadiums, museums, and historic sites. As one producer noted, Ramadan Tent has “significantly popularised the tradition of Iftar dinners, elevating the experience with iconic locations and savvy online presence, creating an aspirational image of modern Muslim culture.” (Producer 6, December 12th 2023)

Screenshot from Ramadan Tent website

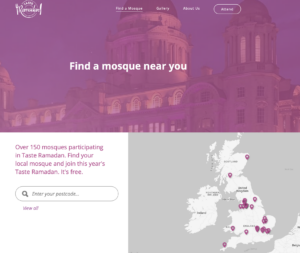

Taste Ramadan is a UK-wide initiative set up in 2017 by the Myriad Foundation (an Islamic charity focused on community outreach and support for those in need based in Manchester) and promoted by Al-Khair Foundation, encouraging people of all backgrounds to experience Ramadan by fasting for a day or joining local communities for the evening Iftar meal at participating mosques. On their website we find a map indicating all the mosques participating in the initiative with days and times.

Screenshort from Taste Ramadan website

A third example from the UK was set up by the Ahmadiyya community called The Big Iftar. This consists of a free one-day event with a three-course meal and a visit of the Baitul Futuh Mosque Complex defined as “Western Europe’s biggest mosque” based in London. The website also provides information about Ramadan, its spiritual and physical benefits, and includes a Q&A section.

Screenshot from The Big Iftar website

Examples from Spain

In Spain, the Unión de Comunidades Islámicas de España (UCIDE), representing over 800 Islamic communities, communicates about public and interfaith Iftar events on its website. Three examples are those organised by three of the organisation’s members: Coexistence Iftar (UCIDCAT, Ibn Battuta and Imed), Interreligious Iftar (Badajoz mosque), and Neighborhood Iftar (Valencia mosque).

Coexistence Iftar (Iftar de la Convivència) was organised in a non-religious location: the Maritime Museum in Barcelona. The organisers were the Unió de Comunitats Islàmiques de Catalunya (Catalan institution of Islamic Communities UCIDCAT), Fundació Ibn Battuta and IMED. The event hosted more than 600 people of different origins and beliefs.

Screenshot from UCIDE website

The mosque of Valencia set up an Interreligious Iftar welcoming a diverse group of individuals committed to interfaith coexistence and understanding. The event was attended by prominent figures including government officials, religious leaders, and academics.

Screenshot from UCIDE website

Finally, UCIDE also communicated on a Neighborhood Iftar organised by the Badajoz mosque. The mosque opened its doors to local residents and representatives of various social associations. The aim of this Iftar was to “promote dialogue with all cultures and faiths”.

Screenshot from the UCIDE website

Examples from Poland

In Poland, a country with a small and dispersed Muslim population, Iftars organized by mosques primarily served to strengthen the sense of community among Muslims. Invitations shared on the websites of Muslim organizations were often addressed to “Brothers and Sisters in Islam.”

Screenshot from the Muzułmański Związek Religijny w RP (Muslim Religious Union in Republic of Poland) website

Screenshot from the Muzułmański Związek Religijny w RP (Muslim Religious Union in Republic of Poland) website

However, some organisations also arranged public and interfaith Iftars. For example, the Danube Dialogue Institute, an organisation dedicated to interreligious dialogue, hosted a series of small Iftar dinners in Warsaw, both at its headquarters and in the private homes of its volunteers.

Screenshot from Danube Dialogue Institute website

In conclusion, public and interfaith Iftars have emerged as powerful tools for fostering interreligious dialogue and community engagement, both in physical and digital spaces. By inviting people of diverse backgrounds to share in the breaking of the fast, these events have contributed to a greater understanding and appreciation of Islamic culture and traditions. The digital realm has played a crucial role in amplifying the reach and impact of these initiatives.

Presenting Ramadan to non-Muslim (or new Muslim) audiences

Webpages can serve as pedagogical tools to explain the significance of Ramadan and promote interfaith dialogue by contrasting it with similar practices in Christianity and Judaism. This is especially important in countries where Islam is an extremely minoritarian religion, such as Poland and Lithuania. Often, Muslims in these countries are converts who are still learning the practices of their new faith.

In the case of Polish OIEs (Online Islamic Envirnoments) two examples of such initiatives were carried out by Salam Lab and The Danube Dialogue Institute.

The website of NGO Salam Lab published four articles around Ramadan 2024. Three of these articles focused on presenting Ramadan, Iftar, and Eid al-Fitr.

Screenshot from Salam Lab website

A fourth article introduced a biscuit called ma’mul which is popular in the Middle East and is also a symbol of interfaith dialogue as it is traditionally prepared both during Muslim Ramadan as well as during Christian Easter feasts.

Screenshot from Salam Lab website

The Danube Dialogue Institute website published excerpts from the article “Ramadan – What Can Christians Learn from Muslims?” (Ramadan – czego chrześcijanie mogą nauczyć się od muzułmanów?), emphasizing the communal nature of fasting in Islam, a dimension often overlooked in Christian fasting traditions.

Screenshot from Danube Dialogue Institute website

A similar can be found in the article posted on the Lithuanian website Islamo Centras. The text introduces the month of Ramadan focusing on the practice of fasting comparing it to similar practices in Judaism (Yom Kippur) and Christianity (Lent).

Screenshot from Islamo Centras website

In conclusion, online platforms like Salam Lab, Danube Dialogue Institute and Islamo Centras effectively introduce Ramadan to non-Muslim and new Muslim audiences. By drawing parallels with similar practices in other religions, these initiatives promote interfaith understanding and religious tolerance.

Conclusion

The digital realm has emerged as a vital platform for Muslim communities from our five different countries to share information and promote understanding during Ramadan. Our analysis focused more specifically on webpages from the UK, Spain, Poland and Lithuania that promote “sharing” Ramadan as a means of fostering (interfaith) dialogue and countering negative stereotypes.

DigitIslam intends to pursue archiving and examining this collection to develop a more in-depth analysis. This data can become a useful tool for researchers and the general public who have an interest in digital Islam across Europe as well as those who are mostly focused on the study of Ramadan. Moreover, the analysis of these sites will be part of a wider project output through presentations and publications.

- The websites we saved for Sweden did not apply to this topic. However, we found an interesting detail: half of the crawled websites were in Bosnian, reflecting the strong ties between the Swedish Bosnian Muslim community and Bosnia.back

Image by Ahmad Ardity from Pixabay