In this extra post, Jayne Quoiani explores how Universal Design for Learning (UDL) can support staff in communicating generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) guidance clearly, why this matters, and what the real cost of failing to design inclusive guidance may be for our students, their progression and their futures. Jayne is Head of STEM at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Open Learning.

Like many colleagues across the University, I’ve been reflecting on how students engage with GenAI tools in their studies. As GenAI becomes increasingly embedded in higher education, students are receiving mixed messages about what is and isn’t allowed. For neurodiverse students in particular, this ambiguity can heighten anxiety and undermine confidence. While the University recognises that developing skills in the responsible use of generative AI is important, and that these skills will likely be significant for students’ future life and work, the practical guidance for how, when and where GenAI can be used is determined at course level. This devolved approach means that students often encounter different rules and expectations across their courses, making it difficult to know what is acceptable. For neurodiverse students, this inconsistency can create barriers to effectively using GenAI tools to support their learning.

Why consistency matters

For neurodiverse students, even small variations in how information is presented or interpreted can have a disproportionate impact on confidence and engagement. When each course communicates its own approach to GenAI, for example using different formats, tones, or levels of detail, the result is cognitive overload and uncertainty. Neurodivergent students often thrive when expectations are clear, consistent, and easy to access; it removes the guesswork and gives everyone a fair chance to succeed.

If course guidelines on GenAI are only mentioned in a few slides of a lecture, hidden away in a Learn page, or written in ambiguous terms, they not only risk being misunderstood but can also create unnecessary anxiety; sometimes to the point where students avoid using these tools altogether for fear of being accused of academic misconduct.

A recent HEPI survey on GenAI found that 80% of students feel their institution’s GenAI policies are clear. But that still leaves many students in the dark:

“I am mostly afraid to use it.”

“It’s still all very vague.”

“It’s not banned but not advised … very mixed messages.”

(HEPI, 2025)

And this isn’t just a UK issue. Similar findings are emerging elsewhere. The Inside Higher Ed Student Voice Survey (2024) published in the US, reported that nearly one-third of students were unsure about when or how GenAI could be used in their coursework. Digging a little further into why this is, it has been found that student nervousness often came from mixed messages about what was allowed, unclear rules around acceptable use, and a fear of getting it wrong. Even when a university puts guidance in place, the way it’s talked about can still vary a lot between courses and lecturers.

In short, students want support and guidance that is clearer, more consistent, and genuinely useful in practice. And for neurodivergent students in particular, the stakes are even higher; as without accessible and consistent approaches, the very tools designed to support learning can instead become barriers.

As a member of staff who is autistic and has ADHD, I also share this challenge. I sometimes find it difficult to work out what exactly counts as ‘permitted’ and ‘not permitted’ use of GenAI under current policies, or even where to find this information. This lived experience helps me to empathise with students who are also trying to navigate mixed messages. If I, with years of experience in higher education, find the guidance confusing, it is easy to see why students might feel anxious or even avoid using GenAI altogether.

The cost of mixed messages

While my focus here is on neurodiverse students, it is important to recognise the wider intersectional picture. More and more literature and survey data point to uneven levels of confidence with GenAI across marginalised student groups. The recent HEPI survey, for example, shows clear gendered and socio-economic divides: women and less economically advantaged students report more hesitation with using GenAI in their studies.

But whole underserved groups are still missing from the picture. This matters because we know from wider evidence that these groups already face barriers in higher education, whether through lower access, reduced confidence, or additional pressures outside of their studies.

All of this underscores the real cost of mixed messages: the widening of the equity gap. Without clear and accessible communication of GenAI guidance, the very students who could benefit most from GenAI as an assistive tool to support learning, may be the ones least confident to engage with it.

Designing against mixed messages

The good news is that mixed messages aren’t inevitable. By drawing on Universal Design for Learning (UDL), we can create guidance that is clear, consistent, and empowering for every student. UDL encourages us to provide information in multiple modes, in simple and intuitive formats, and with reduced room for error in interpretation.

Drawing on UDL, here are a few practices we could try:

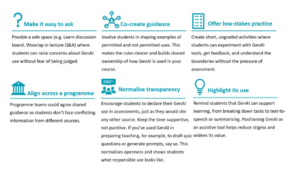

1. Provide written and visual guidance: Create a one-page infographic with Permitted vs Not Permitted GenAI Uses for your course or individual assessments. This can be shared in lectures, uploaded to Learn, and pinned to announcements.

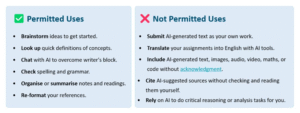

2. Use examples rather than abstract rules: Instead of saying “AI must not be used to generate assessed work”, give concrete prompts for how it can and cannot be used to support learning:

By applying UDL principles to course or programme-level GenAI guidance, universities not only support neurodiverse learners but also create clearer, more consistent expectations for all students. When we design with those at the margins in mind, the benefits extend across the whole learning community.

A call to colleagues

As teaching staff, we are all negotiating this evolving landscape together. I encourage colleagues to:

- Review your course assessments: are your AI expectations stated clearly, unambiguous, in multiple formats?

- Share examples of permitted and non-permitted prompts with your students.

- Work with your programme team to align approaches wherever possible.

- Bring in critical discussions about AI to your teaching.

Small changes like these can make a big difference in ensuring that all students, including neurodiverse learners, feel supported and confident in how they use GenAI.

References

HEPI (2025) Student Generative AI Survey 2025. Higher Education Policy Institute. Available at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/HEPI-Kortext-Student-Generative-AI-Survey-2025.pdf (Accessed: 6 October 2025).

Inside Higher Ed (2024) Student Voice Survey: Generative AI in Higher Education. The Generation Lab – Inside Higher Ed Annual Survey. The Generation Lab – IHE Annual Survey

Jisc (2025) Student Perceptions of AI 2025. Jisc. Available at: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/reports/student-perceptions-of-ai-2025 (Accessed: 6 October 2025).

Stone, R. (2025). Generative AI in Higher Education: Uncertain Students, Ambiguous Use Cases, and Mercenary Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283241305398

Jayne Quoiani BSc (Hons), MRes, PGCE is Head of STEM at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Open Learning. Jayne’s lived experience as a neurodivergent educator shapes her commitment to creating inclusive learning environments where all students can thrive. Her current interests include the role of generative AI in supporting disabled students, academic numeracy development and widening participation pathways into STEM.

Thank you, Jayne, for this thoughtful and timely reminder of the importance of UDL principles. As an inclusive place of learning, we need to keep these in mind in our design and policy application. I work with pre-undergraduate students and the points you make so clearly here apply directly to them. With English as a second or other language, policy documents are often opaque and, ironically, these students are often relying on GenAI tools to translate and explain them. The suggested approach you detail here echoes my own experience in the classroom over the last six weeks and gives us an insightful map of the way forward.

Thank you so much for your kind words Neil and for sharing your reflections. It really means a lot to hear how this connects with your own work with pre-undergraduate students. We see the same challenges with our International Foundation students, particularly where English as an additional language intersects with other factors such as neurodiversity, cultural differences or gender. As you say, policy language can easily become a barrier, and it is often GenAI that students turn to for translation and interpretation. It is encouraging to know that others are thinking about these issues too, it feels like we are beginning to move forward together towards more inclusive practice.