In this post, Dr Inma Sánchez García contemplates Kae Tempet’s book ‘On Connection’ and the notion of intermediality, and how they relate to a pedagogical context where connection and engagement is required for learning to be meaningful and transformative. Inma is a Teaching Fellow in Intermediality Studies at the Department of European Languages and Cultures (LLC). This post belongs to the Engaging and Empowering Learning: Celebrating Best Practices series.

In their recent book, On Connection (2020), the multifaceted artist, Kae Tempest, reflects on the importance of creativity at a time of increased societal tensions, arguing that “creativity encourages connection” (p.8). Their understanding of creativity – or, rather, of what they call “creative connection” – goes beyond traditional views of individual talent. For Tempest, creative connection requires genuine engagement. For art to be like a spark electrifying a circuit, there needs to be a mutual encounter. As Tempest puts it,

Words on a page are incomplete. The poem, the novel or the non-fiction pamphlet are finished when they are taken up and engaged with. Connection is collaborative (…) To really be useful to the connective power of the text, rather than interrogators, we must be the conductors. (p.21)

In reconfiguring creativity as a process that goes beyond the artwork itself, Tempest draws attention to the importance of engagement as fundamental element to foster connection. This can be applied to a pedagogical context since engagement is required for learning to be meaningful and transformative. Knowledge is not just to be interrogated but engaged with – instead of uncovering ‘hidden’ meanings, learners need to bring meaning to the text and be actively involved in the act of knowledge creation.

“True engagement”, as Kristen Cowan aptly writes in the introduction to the first series in this theme, “extends beyond simply capturing students’ interests” and involves active participation and a genuine “desire to learn”. By situating students as active agents of their own learning, teachers can’t ask students to simply “receive, memorize, and repeat (…) [as] merely spectators, not re-creators” of knowledge (Freire, 1968, p.62). For education to be empowering, our classrooms should be collaborative spaces in which knowledge is co-constructed through student engagement.

However, what constitutes student engagement? Is vocal expression the main indicator of active participation? If a student is pensive but silent, inwardly reflecting on their knowledge, can it be viewed as engagement? To what extent can engagement be considered in relation to students who are adverse to verbal participation in class? Addressing what she calls “the tyranny of participation”, Lesley Gourlay (2015) argues that mainstream conceptions of student engagement emphasise practices which are observable, verbal, communal and indicative of ‘participation’, and that private, silent, unobserved and solitary practices may be pathologised or rendered invisible – or in a sense unknowable – as a result, despite being central to student engagement (p. 410, emphasis added).

Moving beyond facile dichotomies that situate verbal expression and silence at two ends, there is a need to understand engagement by considering participation beyond verbal expression, thus capturing the “silence” that some students may prefer. This, however, does not equal a lack of engagement. The centrality of the word risks excluding different ways of participation and, in so doing, overlooking non-verbal modes of engagement in which some students may excel.

Intermediality: Diversifying modes of engagement

Verbal engagement, however, need not be replaced by visual communication or other forms of expression; instead, diverse modes can harmoniously complement one another. Intermediality – the intersection between different media forms and their signification – draws attention to the in-betweenness of media. The term, while foregrounding the transformative power across and in-between media, acknowledges that differences between media do exist; as such, media boundaries need to be respected but they can also be crossed. In this way, intermediality can be offered as a tool for student engagement to foster verbal, non-verbal, or simultaneously verbal and non-verbal participation.

The use of activities that combine two or more media can facilitate engagement in diverse ways, going beyond the exclusive prevalence of verbal expression. In my teaching practice, I have found that tasks that include not just verbal and visual elements but also haptic and kinetic modes of expression are particularly helpful to diversify learning and encourage participation.

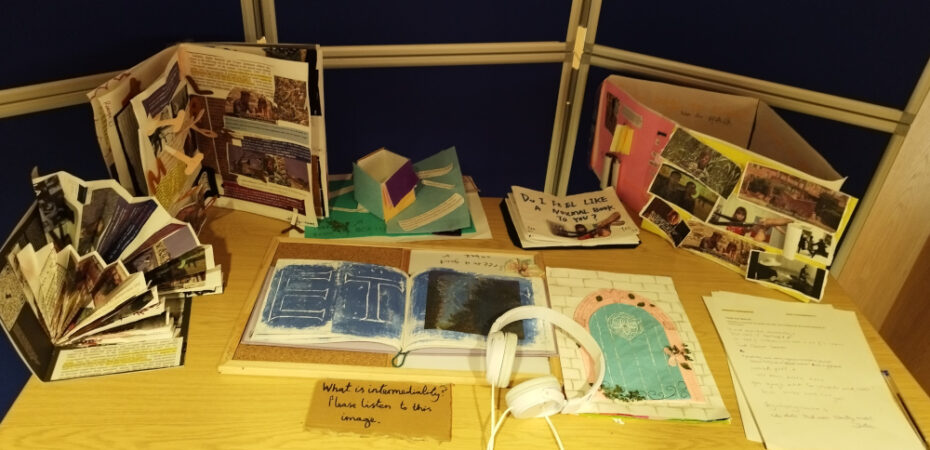

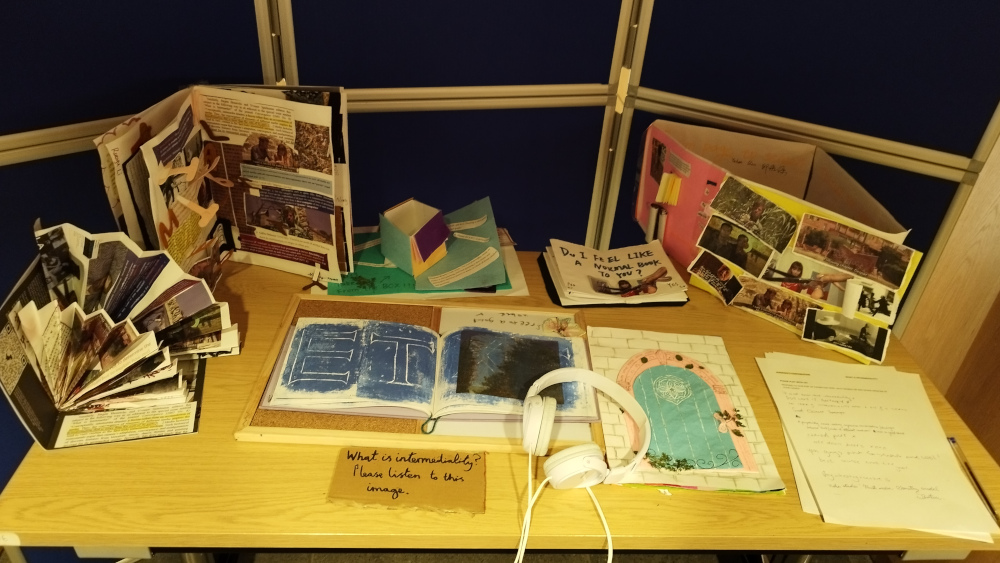

An example from my current teaching practice is the creation of artists’ books by students; that is, a book that emphasises its form as an artistic or performative object, including elements of interaction to invite the reader-as-audience to participate in the meaning-making process. In the past two years, I have asked students to create artists books around one topic by giving them a curated set of images and texts (with excerpts from relevant theoretical readings) alongside various DIY materials, such as tape, scissors and coloured fabric to create tactile effects.

Practical activities that encourage the use of words in combination with images, videos, sounds, objects, space, and/or gestures in a collaborative context are particularly helpful to diversify engagement. Every time I bring what I call a flash intermedial project, my students surprise me with their creativity and inspiring team-work ethos, creating intellectually stimulating art installations, theatrical performances, or Lego constructions with limited materials and in short spans of time during tutorials. Intermedial activities offer a creative way to address complex ideas while accommodating diverse learning styles, engagement modes, and student skills.

Creative connection and the attuned teacher

As we move towards authentic learning, we need to reflect on how best we can stimulate student engagement but also on our own role as teachers while students participate. Incorporating a holistic approach to education based on trust, care and connection is also fundamental to ensure genuine engagement, since it has been demonstrated that “learning itself is an emotional activity” (Tangney, 2013, p. 273). For the connective circuit to be activated, teachers need to be enthused participants as well. As educators, we should spark student desire to learn, but we should also show to students that they spark in us the desire to be actively involved in the learning process. In going beyond words, and to paraphrase my former student, Evan Falls, intermediality can be an electrifying force – and, in fostering creative connection, intermediality can help us capture the ineffable.

References

Cowan, Kirsten. 2024. “Welcome to Oct-Nov learning & teaching enhancement theme: Engaging and empowering learning at The University of Edinburgh”, Teaching Matters.

Freire, Paulo. 1968. Pedagogy of Oppressed. Penguin, 2017.

Gourlay, Lesley. 2015. “‘Student engagement’ and the tyranny of participation”. Teaching in Higher Education 20 (4): 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1020784

Tangney, Sue. 2013. “Student-Centred Learning: A Humanist Perspective.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (3): 266–75. doi:10.1080/13562517.2013.860099.

Tempest, Kae. 2020. On Connection. Faber & Faber.

Inma Sanchez Garcia

Inma Sanchez Garcia

Dr Inma Sánchez García is Teaching Fellow in Intermediality Studies at the Department of European Languages and Cultures (LLC). She joined the University of Edinburgh in 2021, when the MSc in Intermediality was launched, and in 2024 she became a recipient of the EUSA CAHSS Teacher of the Year Award. As part of the Intermediality programme, she convenes and teaches courses on global Shakespeare, film adaptation, and intermedial theories and methods. Her research examines political and interartistic adaptations of Shakespeare’s work across contemporary non-Anglophone cultures and she is part of an international research project on Shakespeare and activism.