In this post, Heather McQueen reflects on her work using two-part assessments over the last ten years, what still works well, and what we still have to learn. Heather is Professor of Biology Education within the School of Biological Sciences. This presentation is part of the ‘Transformative Assessment and Feedback’ Learning and Teaching Conference series.

Enjoying and learning from assessments.

At this year’s Teaching and Learning Conference, a team of four from our new first-year core biology course ‘Biology 1B: Life’ showcased our favourite assessment: the creative task. This is a fun and relaxed low-stake assessment that is more about agency, community and engagement than about course content. However, my other favourite assessment on this course – the two-part concept test – is all about understanding core content. It is our highest stake assessment, worth 25% of the course. So why would a lecturer enjoy an assessment?

Picture the moment. It’s the final day of class and the students have just finished their main course assessment. Emotions are running high. Students are eagerly exchanging answers and explanations. The two-part assessment captures this moment while students are fired up and invested in understanding the right answer and turns it into useful learning.

What is a two-part assessment and how did it get in our course?

I first learned about two-part assessments in 2014 from ex-Edinburgh University colleague Prof. Simon Bates who is now Vice-Provost and Associate Vice-President Teaching and Learning at the University of British Columbia where two-stage exams are in widespread use (you can watch this short video). The two-part assessment involves students sitting and submitting the assessment individually under exam conditions. It is followed immediately by group discussion and re-submission of the group’s agreed answers to each question in the exam paper. This second group score is then used to adjust the score of each member within the group, assuming it is higher than the individual sit, as is normally the case (Zipp, 2007).

In 2015 and 2016, while on secondment to the Institute for Academic Development, I ran two-part assessments for my second and third-year genetics students. The assessment, my reflections and the students’ responses were captured in a Teaching Matters video round-up:

The experiment was so successful that we now use the two-part format for the main summative assessment in ‘Biology 1B: Life’, which has been running since 2022.

What have we learned from using this assessment?

After three iterations of ‘Life’ and adoption of the technique by another biology course (featured at this year’s Learning and Teaching Conference), it seems timely to look back at the original video round-up and to reflect on the last three years of two-part assessments, to consider how things have changed and could change further.

Firstly, I still firmly believe that the two-part test is a fantastic way to learn from assessments and I love the positive buzz in the room. There are loud exclamations and high fives as answers are agreed. There is laughter and shouting and slow, dawning realisation on faces as misunderstandings begin to dissolve. This is a happy assessment even for students who have struggled with the individual sit because they know they have now improved their score, and their grasp on the concepts. Students learn and leave happy. How could I not love this?

A second thing that has not changed is the design of the test to assess understanding of concepts. Multiple choice can be so much more than a memorise and regurgitate exercise.

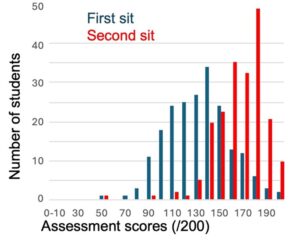

One thing that has changed is the proportion of marks attributed to the group component. Originally 5% of the final mark came from the group score but students were disappointed that the resultant score boost was not significant. On learning that a colleague at Bristol University apportioned 15% to the group score, and after asking the students if they liked this idea (they did), we tripled the group score component. This raises the incentive to get the right answers in the group. Because individual scores must be adjusted to 85% no-one receives a full 15% boost. Second-sit scores are, however, markedly improved compared to individual scores (Figure 1) providing reward to students for their collaborative efforts.

What do we still have to learn about the two-part assessment?

In the 2016 video, I suggest that the test works well because our students are ‘of such high calibre’. While this may be true, a deeper and more inclusive consideration of how the test is experienced now seems timely. Rising numbers of students with adjustment schedules, extensions and exceptional circumstances clearly display that students are struggling, and this is where the gloss may start to peel.

There is an assumption that interactive learning methods such as the two-part test support students including those with learning differences or ADHD, but evidence suggests that this is not always the case (Pfeifer et al., 2023). The benefits of this test are evidenced by score uplift and the useful and effective peer-learning that we witness but is there a cost for some? We intend that the considerable support for group work throughout this course will provide a supportive environment where students with learning or neuro-developmental differences can learn effective coping strategies. In advance of the test, we consult students with adjustment schedules (requiring extra time or consideration for groupwork) to ask whether they want to join the group component of the test. To date, all have done.

But is this really a choice? Does the group sit lure students into a situation that is unreasonably difficult or aversive to them? Does the test help or hurt these students? We simply do not know but it feels like time to find out (Pfeifer et al., 2023).

Read related posts about course design in Biology here:

- Forming groups by shared interest: Staff and student perspectives

- Student creativity at the centre of the new biology curriculum

- Belonging in the new biology curriculum

References

Pfeifer, M.A., Cordero, J.J., Dangremond Stanton, J. (2023) What I Wish My Instructor Knew: How Active Learning Influences the Classroom Experiences and Self-Advocacy of STEM Majors with ADHD and Specific Learning Disabilities CBE—Life Sciences Education, 22, (1). https://www.lifescied.org/doi/10.1187/cbe.21-12-0329

Zipp, J.F. (2007). Learning by Exams: The Impact of Two-Stage Cooperative Tests. Teaching Sociology, 35(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055×0703500105

Heather McQueen

Heather McQueen

Heather McQueen is Professor of Biology Education within the School of Biological Sciences. Her current academic interests lie in active learning techniques, student engagement in large classes and inclusive education, but she is also passionate about canine learning. She is the course organiser and lead developer of the new first year biology course Life 1, and is SFHEA and a National Teaching Fellow.