by David Fox, Professor of Common Law, University of Edinburgh

Introduction

As we saw in the first part of this blog entry, Paulus explains all three of the exchange transactions in the Homeric texts as instances of permutatio. If we focus only on the material things passing in each direction, that characterisation seems accurate enough. But that view would overlook the non-material differences among them, which in Homeric times would have separated the transactions into distinct kinds of exchange. Each had a different motivation which would have placed it in a distinct domain of social activity. The distinctions among them become still more blurred if we translate permutatio simply as “barter”, which has connotations of a commercially-motivated exchange, one that differs from purchase only in the absence of money.

A scheme of reciprocity in exchange

In Stone Age Economics (1972), the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins proposed a scheme to characterise the reciprocal exchanges of material resources in primitive societies. Resources were generally distributed through socially embedded networks of gift.[1] The cohesion of the network depended on expectations of reciprocity among the participants. The beneficiary of the gift was always bound to reciprocate in some way, although the content, value and immediacy of the return might differ from one type of transaction to another. Material transactions could rarely be treated in isolation: every one of them was, as Sahlins explained, “a momentary episode in a continuous social relation”.[2]

The inspiration for Sahlins’ social view of primitive economies was not new. Sahlins developed a line of thought traceable to Marcel Mauss’ classic work on The Gift (1925).[3] Mauss emphasised that all gifts are made in the context of shared expectations of reciprocity. The transfer of wealth or property in the object of the gift was only one element of a “total” social phenomenon.[4] This social view of primitive economies found its clearest expression in Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation (1944).[5] Polanyi argued that Adam Smith’s explanation of market economies based on man’s natural propensity for “barter, truck and exchange” – all motivated by economic self-interest – was a misreading of the past, whatever influence Smith’s theory might have exerted on economic thinking of the 19th and 20th centuries that came after him.[6] The “functions of a [pre-modern] economic system proper were completely absorbed by the intensively vivid experiences which offer superabundant noneconomic motivation for every act performed in the frame of the social system as a whole.”[7] Like Mauss, Polanyi’s understanding of the pre-modern, pre-market world was one where the economy was embedded in social relations. This contrasted with the understanding that took hold during the nineteenth century that “social relations are embedded in the economic system” and that social relations are subsidiary to the market.[8]

Sahlins’ advance was to explain all instances of material exchange as degrees on a continuous spectrum of reciprocity. The spectrum began with what he called “generalised reciprocity” at one end, which gradually blended into “balanced reciprocity” near the centre, and then ended with “negative reciprocity” at the opposite extreme. The following summary can provide only the barest outline of the many dimensions to Sahlins’ scheme.

Generalised reciprocity referred to the kind of transaction that came closest to pure gift. The voluntary sharing of food among kinsmen or the nurturing of children in a household were the clearest examples. Here the compelling social motives for the transaction subsumed any material reasons for making it. The expectation that the beneficiary of the gift would reciprocate was real but wholly indefinite in content – it was “not stipulated by time, quantity or quality”.[9] Children would grow up, and one day they would provide work and care in support of their parents but neither side kept any careful reckoning of the benefits given to or due from the other.

Balanced reciprocity indicated a direct exchange. Here the return for the gift was made without delay and in the customary equivalent of the thing first given. Balanced transactions would generally occur among participants who were at some distance from each other, such as where they belonged to different households or kinship groups. Distinctively commercial motivations might sometimes impinge in balanced transactions but the making and reinforcement of social bonds were no less important. Instances of balanced reciprocity included the range of transactions where useful goods were traded by people unrelated by kinship or tribal ties, but it might also include ritualised exchanges of gifts between friends or allies.

Negative reciprocity tended to be found among people who were socially distant from each other and who held opposing interests. Transactions in this range were conducted with a view to “net utilitarian advantage”.[10] At the more sociable end of the range, negative reciprocity might show some features of balance, as where parties made an arms-length barter of goods to maximise their personal gain. At the more extreme end, it would extend to raiding a stranger’s livestock or sacking a city for plunder. The reciprocity here involved an expectation of a counter-raid or retribution.

Reciprocity in Paulus’ Homeric texts

Polanyi’s “embedded” economy and Sahlins’ scheme of reciprocities have been influential in shaping understandings of the ancient economies of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East. They have served as models for framing the allocation of material resources in the pre-coinage economy of the Homeric era.[11] For our purposes, they bring to light the non-material context to the three Homeric texts cited by Paulus. They show the subtle differences among the transactions in personal motivation and social context which are blurred by the simple characterisation of them all as permutatio.

The first transaction where the Achaeans procured wine and the third where Laertes obtained Eurycleia are the most alike of the three Homeric texts. Each falls in the range of balanced reciprocity, though they also have elements of utilitarian self-interest that bring them nearer the negative end of the spectrum. They may fairly be described as barter in the modern sense. Each shows an obvious commercial motive.

Both transactions are immediate exchanges, or at least ones where the counterperformance by the beneficiary was expected very soon afterwards. Homer describes the trade for wine happening at the harbour, with the Achaeans producing their useful metals, hides, cattle and human captives at the same time as the wine is being unloaded from the ships. When Laertes acquired Eurycleia, he might have needed a little time to assemble the 20-cattle worth of belongings from his storeroom, and presumably the traders he dealt with had to be satisfied that they were a proper equivalent to the agreed cattle “price”. But the deal was closed promptly and afterwards neither side owed any continuing duties to the other.

Both texts describe arms-length transactions between people who were relative strangers. If Laertes acquired Eurycleia from traders who dealt in enslaved captives (which seems likely), then they would have been fully outside the range of Laertes’ household or kinship alliances. Trade, as we might now understand it, was reserved for deals with foreigners. Traders were generally held in contempt by the Homeric elites: the elites would never stoop to trading for a livelihood. They preferred to get the resources they needed by expanding domestic production in their own households, receiving gifts of tribute from their subordinates, making gift-exchanges with their social equals, and by plunder in war.

We can detect shades of difference even between the transactions for Eurycleia and for the wine. The presence of professional traders in the Eurycleia transaction brings it closer to the negative end of the spectrum. The transaction where the Achaeans acquired wine is less clearly negative in character since the wine had been sent by a certain nobleman, Euneus of Lemnos, who seems to have been an ally of Agamemnon and Menelaus, the leaders of the Achaean armies. Homer mentions as an aside that Euneus sent a separate consignment especially for Agamemnon and Menelaus.[12] The whole wine consignment was made in recognition of a personal loyalty owed to them, and the leaders themselves, unlike their allies and subordinates, were not expected to make a direct return in exchange for it.

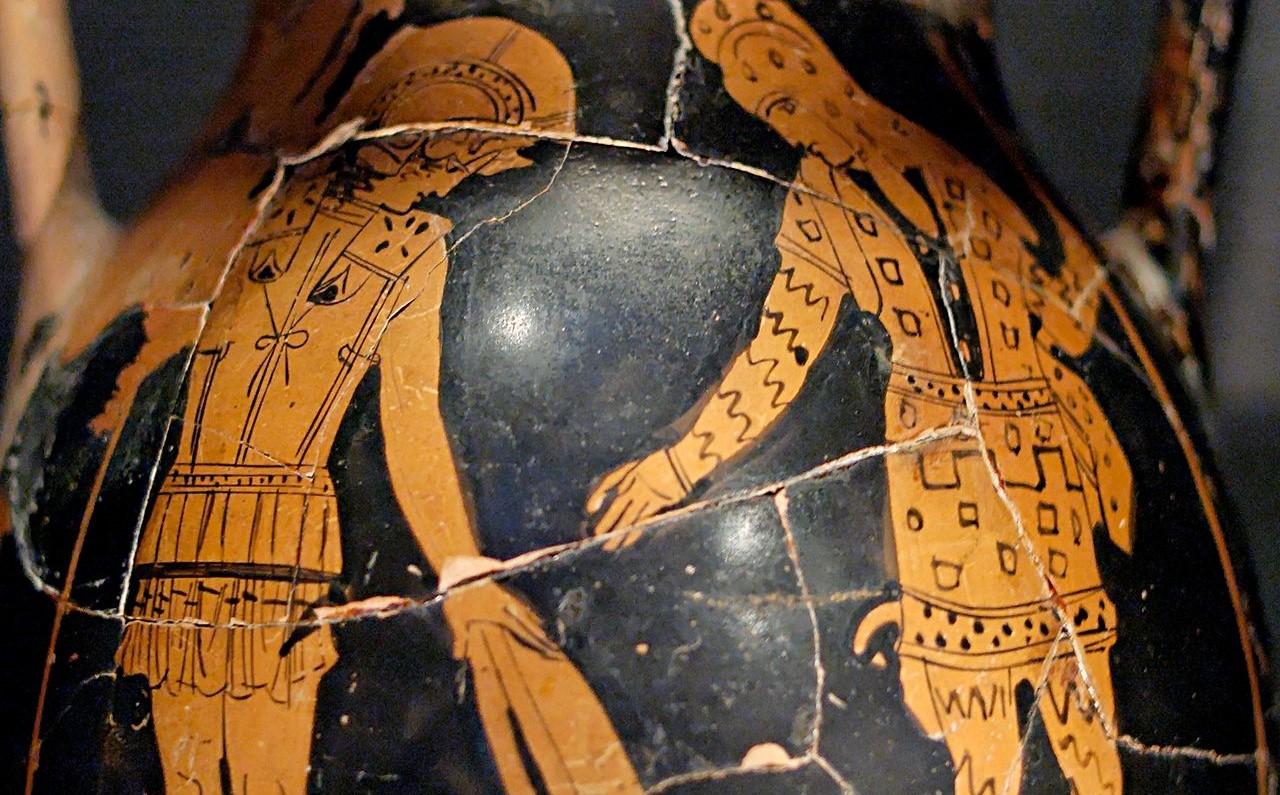

The exchange of armour between Diomedes and Glaucus falls in an entirely different range of Sahlins’ scheme. True, it can be characterised as a balanced exchange but the motivation and the subject matter take it outside the domain of utilitarian trade. Narrow economic motives do not figure in it. The transaction is a double-layered exchange of gifts to reaffirm a long-standing social bond between two men of high social status.[13]

Though Diomedes and Glaucus had not met each other before, they were linked by an inherited relationship of guest-friendship (xeinos patrôios) between Glaucus’ grandfather Bellerophon and Diomedes’ forefather Oeneus.[14] This is the first layer in explaining the exchange. Oeneus had once offered hospitality to Bellerophon in his house. In a world order where members of foreign communities treated one another as strangers (and presumptively as enemies), guest-friendship was a valued exception to the ordinary norm. Hospitality to visiting strangers was a divine duty overseen by Zeus. Any failure of hospitality breached one of the few expectations of civilised humanity that were shared across all peoples. The breach justified retribution, if not by Zeus himself then maybe by the guest who had put himself at the mercy of his host, only to find himself spurned. At a personal level, guest-friendship brought the visitor within the temporary protection of the host’s household. It had a larger political significance too. The Homeric world was one of fragmented communities where a king’s power and external influence depended on his personal prestige. Guest-friendship among people of high social standing established alliances across communities.

The guest and host would symbolise their relationship by exchanging precious gifts. Thus Oeneus gave Bellerophon “a shining belt adorned with purple” and Bellerophon gave a double-handed golden cup in return.[15] Seen in purely material terms, this exchange of gifts was a way to circulate valuable treasure among social elites, something like a transfer of sovereign capital between modern states. In that sense, it served an economic function. But the gift objects enjoyed a status that lifted them above regular trade and ordinary expectations of value. The stories surrounding their acquisition gave the objects their own identity. Diomedes tells Glaucus that he had left Bellerophon’s cup at home when he left for the war – he clearly knew it by sight. The cup had a lineage that marked it out from ordinary goods, just as Diomedes’ and Glaucus’ respective lineages excepted them from the enmity due between Achaeans and Trojan allies.[16]

The second layer to the transaction between Diomedes and Glaucus is the exchange of their own armour. It reaffirms their forebears’ guest friendship and marks a new personal peace between them. Diomedes proposes that they will not fight each other (though he adds the grim heroic boast that each would find plenty of other opponents to kill).[17] The exchange of armour concludes the peace pact between them.

Conclusion and implications

We return to the opening text of Book XVIII of the Digest. For Paulus the presence of money on one side of an exchange transaction marked the division between different categories of contract in private law. A thing given in return for money was the subject of a purchase and any other exchange of things was generalised as a permutatio. But a closer study of the Homeric texts shows how that generalisation obscures the full detail of the transactional types comprising the situations where one thing is exchanged for another. The parties make them for different motives and expect different kinds of counter-performance in return. Not every kind of non-monetary exchange can fairly be typed as a barter.

The coined money that was first struck after Homer’s time was a specialised kind of exchange object. In ways that were impossible before the invention of coinage, money has become the marker between the commercial domain of human activity and the social or domestic domain beyond commerce. More subtly, it has played a part in defining the positivist reach of private law. We often find that only transactions made for money or money’s worth attract legal recognition and benefit from the special kinds of enforcement that the law affords. That too may be another consequence of Adam Smith’s partial reading of nearly three millennia of economic history. The rich spectrum of social reciprocity found in the works of Homer has now become subsidiary to a dominant view of legal positivism embedded in a market economy. Monetary value often determines what is within and without private law transactions.

[1] M Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (1972, 2004), ch 5.

[2] Sahlins (1972, 2004), 185-186.

[3] M Mauss, (M Douglas (ed)), The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies (1925, 2002).

[4] Mauss (1925), ch 1.

[5] K Polanyi, (F Block and G Dale (eds)), The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Times (1944, 2001).

[6] Polanyi (1944, 2001), 50.

[7] Polanyi (1944, 2001), 56.

[8] Polanyi (1944, 2001), 66.

[9] Sahlins (1972, 2004), 194.

[10] Sahlins (1972, 2004), 195.

[11] K Polanyi, chs 5, 13 in K Polanyi, C M Arensberg and H W Pearson, Trade and Market in the Early Empires (1957); M I Finley, The World of Odysseus (1954, 1982), chs 3-4; M I Finley and I Morris (ed), The Ancient Economy (1985), ch 1; S von Reden, Exchange in Ancient Greece (1995), Introduction, chs 1-3; R Seaford, Money and the Early Greek Mind: Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy (2004), ch 2; S von Reden, Money in Classical Antiquity (2010), Introduction; W Donlan, “Reciprocities in Homer” (1982) 75 Classical World 137; W Donlan, ch 28 in I Morris and B Powell (eds), A New Companion to Homer (2011).

[12] Il.7.470-471.

[13] See especially Finley (1954, 1982), 99-104; W Donlan, “Reciprocities in Homer” (1982) 75 Classical World 137, 148-151; W Donlan, “The Unequal Gift Exchange between Glaucus and Diomedes in the Light of the Homeric Gift Economy” (1989) 43 Phoenix 1.

[14] Il.6.215-217.

[15] Il.6.219-220.

[16] See generally von Reden (1995), ch 1.

[17] Il.6.227-229.