by David Fox, Professor of Common Law, University of Edinburgh

Introduction

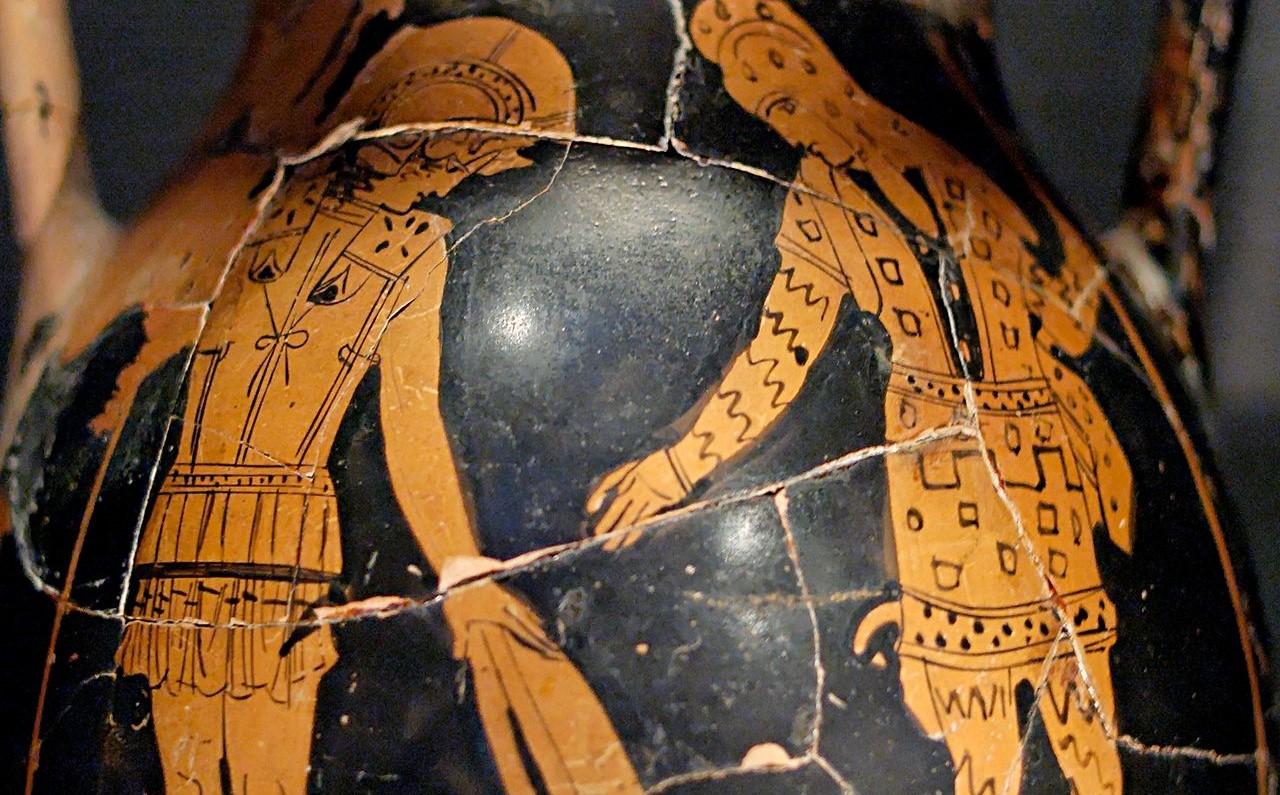

As we saw in the first part of this blog entry, Paulus explains all three of the exchange transactions in the Homeric texts as instances of permutatio. If we focus only on the material things passing in each direction, that characterisation seems accurate enough. But that view would overlook the non-material differences among them, which in Homeric times would have separated the transactions into distinct kinds of exchange. Each had a different motivation which would have placed it in a distinct domain of social activity. The distinctions among them become still more blurred if we translate permutatio simply as “barter”, which has connotations of a commercially-motivated exchange, one that differs from purchase only in the absence of money.

Leave a Comment