by David Fox, Professor of Common Law, University of Edinburgh

Introduction

The opening text of Book XVIII of Justinian’s Digest, on the contract of purchase, quotes an excerpt from Paulus’ Commentary on the Edict.[1] In this text, Paulus develops a legal test for distinguishing two kinds of exchange: the contract of purchase (emptio) on the one hand and the contract of barter (permutatio) on the other. Purchase, he says, consists in one party paying a money price (pretium) in exchange for the thing (merx) that is promised and delivered by the other party. By contrast, a barter is a transaction where the parties promise and exchange two non-monetary things.

Paulus goes on to develop a sharp definition of money for the purposes of his rule. The monetary price, he says, should consist in coins (nummi) struck in authorised form by the public mint. For Paulus, the delivery of coined money on one side of the exchange marks the identifying characteristic of a contract of purchase.

Justinian authoritatively accepted Paulus’ view.[2] His ruling put beyond dispute that purchase and barter were distinct contracts in the revived Roman law of the sixth century AD, and that each had to be enforced by its own distinct actions. In so ruling, he settled an old disagreement between the Sabinian and Proculian schools of juristic thought.[3]

All this is familiar to students of Roman law.[4] However, one curious thing about the text is that Paulus cites three passages from Homer’s epic poems, The Iliad and The Odyssey, to support his argument. He says they are all instances of barter rather than purchase, presumably since neither party to the exchange handed over any coined money. He disagrees with Sabinus who had referred to one of these texts to illustrate his own view that purchase and barter were the same kind of transaction. Whatever might have been the looser ordinary usage (vulgo) in the past, says Paulus, the categories of exchange transactions in his own time (the early third century AD) had evolved into distinct categories of contract. Justinian’s later ruling put this beyond argument.

Paulus’ use of those Homeric texts is the subject of this two-part blog entry.[5] At one level, the texts are problematic as sources to support his argument about legal categorisation in the classical Roman law of contract. Coined money had not been invented when Homer composed The Iliad and The Odyssey in the early decades of the eighth century BC. Still less could it have existed at the time of the Trojan war and the journey of Odysseus that Homer projected into an imagined era many generations earlier. The texts present a curious anachronism. Paulus could not make a like-for-like comparison between forms of exchange happening at such markedly different stages of economic development. Paulus and Homer were a millennium apart, as were the kinds of economy that each might have known.

At another level, the Homeric texts are richly informative. They show how people in Homer’s own time might have acquired the things they needed by making transactional exchanges without offering coined money. They provide a more refined insight into workings of the non-monetary exchanges that Paulus grouped together as barter (permutatio). The parties found ways of reducing their exchanges to a balanced equivalence even if one of them was not offering coined money to the other. That is the subject of the first part of this blog entry.

The second part, to be posted shortly, will go on to show the very different motivations that made people exchange valuable goods in the Homeric era. The transactions belong to an era before the motive of monetary gain allowed specialised ideas of economic exchange to be separated from more general ideas of social reciprocity. They are good examples of the pre-modern “embedded” economy, famously described by the economic historian Karl Polanyi in The Great Transformation (1944),[6] and then theorised into a typology of reciprocities by the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins in Stone Age Economics (1972).[7] They remind us that the line dividing economic and social exchange has been drawn differently across times and societies. Drawing the line is especially hard if there is nothing like coined money (or an obligation to pay money) to mark it out.

The three Homeric texts

Paulus’ first Homeric text was also the one cited by Sabinus to support his view that a contract of purchase might include the exchange of one non-monetary thing for another. Drawn from Book VII of The Iliad, it describes a transaction by the Achaean armies to acquire quantities of wine sent to them from the isle of Lemnos.[8] The wine was to be drunk at a funeral feast to commemorate the slain Achaeans whose bodies had been gathered from the battlefield at the end of a day’s bloody conflict.

| enthen oinizonto karê komoôntes Achaioi, | The long-haired Achaeans came there to the harbour to trade for wine, |

| alloi men chalkôi, alloi d’aithôni sidêrôi, | some trading with bronze, some gleaming iron, |

| alloi de rinois, alloi d’autêisi boessin, | some with cattle hides, and some living cattle, |

| alloi d’andrapodessin … | and others with human captives … |

Here we have an exchange of metals, hides, cattle and human captives in return for great quantities of wine. The key verb is oinizonto, which in its lexicographical form is oinizomai. Although English translations render it as “bought” wine[9] (which has connotations of acquisition in a monetary transaction), it has a more general meaning, referring to any transaction where one person procures wine from another.

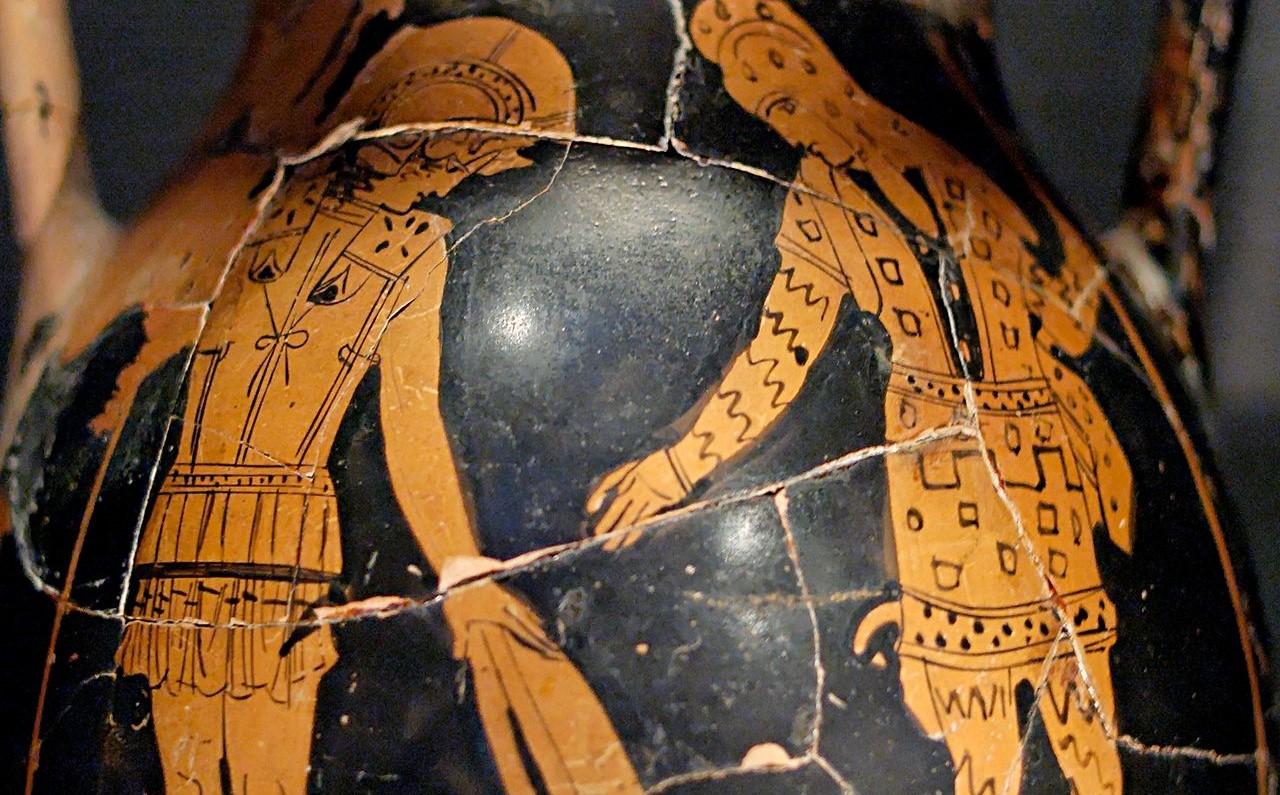

The second Homeric text was one sourced by Paulus himself as an example of barter. It is taken from Book VI of The Iliad, and describes an exchange of armour between combatants on the battle plain before Troy.[10] The hero Diomedes, fighting for the Achaeans, pauses in the slaughter to challenge Glaucus, a Lycian noble fighting as an ally to the Trojans. They exchange long speeches, which explain their genealogy and their status as guest-friends (xeinos patrôios … palaios) established through the hospitality shown by Diomedes’ forebear, Oeneus, to Glaucus’ grandfather, Bellerophon. Diomedes and Glaucus swear a personal truce and exchange gifts of their armour. This transaction symbolically re-enacts their forebears’ exchange of gifts which first established the relationship of guest-friendship. This personal alliance is strong enough to exempt them from the usual loyalties that each would have owed to their leaders in battle.

| Hôs ara phônêsante, kath’ hippôn aïxante, | When they had so spoken, they both leapt from their chariots, |

| cheiras t’allêlôn labetên kai pistôsanto: | took each other by the hand and swore oaths: |

| enth’ aute Glaukôi Kronidês phrenas exeleto Zeus, | but then Zeus son of Cronus took away Glaucus’ wits |

| hos pros Tudeïdên Diomêdea teuche’ ameibe | and he exchanged his armour for the armour of Diomedes, son of Tydeus, |

| chrusea chakeiôn, hekatomboi’ enneaboiôn. | gold for bronze, a hundred cattle-worth for nine. |

The verb describing the transfer made by Glaucus is ameibe. Its usual lexicographical form is ameibô, which in its core meaning is translated as “exchange (with another)”.[11] Glaucus’ act of panicked folly was to give away his golden armour worth a hundred head of cattle in exchange for Diomedes’ bronze armour worth just nine. The seeming inequality of their exchange has been a subject of debate since antiquity.[12] Paulus’ citation of the text was drawing on a well-known literary trope. To Aristotle, for instance, it raised the question whether an objectively disadvantageous action could ever be unjust if the person who performed it acted voluntarily.[13]

Paulus’ third, very brief, reference to Homer is taken from the end of Book I of The Odyssey. The three words quoted (priato kteastessin heoisi) are extracted from a longer passage telling how Odysseus’ father, Laertes, had obtained a captive woman, Eurycleia, for his household many years earlier. Eurycleia was a nobleman’s daughter who had fallen into slavery. Laertes acquired her in exchange for a quantity of his own possessions and made her nurse to the young Odysseus. Eurycleia’s unflinching devotion in performing this role carried over to the next generation. She became the nurse to Odysseus’ own son, Telemachus, and was still doting on him as a young man in his early twenties at the start of the poem.

| Tôi d’ar’ ham aithomenas daïdas phere kedna iduia | A loyal slave, Eurycleia, the daughter Peisenor, |

| Euruklei’, Ōpos thugatêr Peisênoridao, | carried the flaming torches before him. |

| tên pote Laertês priato kteatessin heoisi, | Laertes acquired her with his own goods |

| prôthêbên et’ eousan, eeikosaboia d’edôken | when she was still in the prime of her youth, giving twenty cattle-worth for her. |

The terms of the transaction where Laertes acquired Eurycleia are carefully explained. Priato, from the lexicographical form priamai, is a general word referring to a transaction of acquisition. Some translations render the key words in this passage as “bought with his own possessions”,[14] which again has potentially confusing connotations of buying with money. The possessions (kteatessin) which Laertes gave in exchange refer to any objects of patrimonial wealth. They would have derived their value from the possibility of being given in commercial exchange. These possessions were not necessarily a herd of twenty live cattle. Eeikosaboia is a compound adjective, indicating a generic unit of multiple value. The possessions that Laertes parted with, whatever they were, might be understood more accurately as “20 cattle-worth”, just as Glaucus’ golden armour was “100 cattle-worth” and Diomedes’ bronze armour a mere “9 cattle-worth”.

Valuation of things by head of cattle

All three texts illustrate aspects of exchange transactions happening before the invention of coined money. The first electrum coins were struck in the cities of Asia Minor about 600 BC.[15] Harder to pinpoint is the dating of Homer’s composition of The Iliad and The Odyssey, though modern interpretations set that in the range c 750-740 BC.[16] While the stories told in the epics are works of mythical invention, the mainstream view has settled that they at least present a tenable view of the social and economic practices of Homer’s own day, which was some 150 years before coins appeared.[17]

Even if they had no coins to spend, the people of Homer’s time did not lack in their understanding of monetary reasoning. It was common in ancient economies for the distinct monetary functions of denominator of value and medium of exchange to be performed by different kinds of thing. An exchange might look outwardly like a simple barter – with goods given in return for other goods – but the valuation which fixed the equivalence of the exchange was not left to chance. Head of cattle served as a denominator of value, at least for goods of high worth. The advance made by coinage, as Paulus recognised, was that the thing offered by the “buyer” was at once the medium for performing one side of the exchange and a representation of the abstract value exchanged in the transaction. It thus ensured the direct equivalence of the exchange.

The works of Homer are replete with examples of cattle valuation, alongside those quoted by Paulus. At the funeral games of Patroclus in Book XXIII of The Iliad, the prizes include a huge tripod valued at twelve head of cattle and a skilled serving woman valued at four.[18] (The high price of 20 cattle-worth offered by Laertes for Eurycleia doubtless reflected her elevated social status in her former life and the strength of his attraction to her.) As elsewhere, the valuation is expressed as a compounded adjective: duôdekaboion and tessaraboion, respectively.

We need not suppose that there had been earlier transactions where herds of cattle were delivered in return for the forging of the tripod or for the ownership of the serving woman. (She, at least, would have been one of the sad spoils of sacking another city.) That is to say, a counter-performance denominated in cattle need not imply that live cattle were the actual subject of the counter-performance. We see from the wine transaction, for example, that many kinds of possession, aside from live cattle, might have been offered. The same must be true for the respective valuations of Glaucus’ and Diomedes’ armour. However the economist Adam Smith might later have understood their exchange,[19] the text surely refers to the value of the armour not the form of any earlier transactions by which Glaucus and Diomedes procured it from its makers. In other contexts, a ritual sacrifice of enormous value was known as a hekatombê (literally a 100 cattle-worth), whatever animals might have gone to the slaughter.[20] Even things belonging to the gods might be open to valuation by head of cattle. Each of the hundred golden tassels on the aegis cloak worn by Zeus and Athene was valued at 100 cattle-worth.[21] It would be unreal to suppose that these leading figures in the Olympian family had engaged in a cattle trade with the divine goldsmith who made the tassels.

These exchanges of objects for objects are surely the ones that Paulus had in mind in characterising them all as examples of barter. To that extent, there are some similarities among the three texts, which is why he might have reduced them all to the same transactional type. At another level, however, they are each markedly different kinds of exchange, which the later distinction between purchase and barter fails to capture. The second part of this blog entry will explain why they are different and why that matters to understanding their full significance.

(To be continued.)

[1] D.18.1.1.pr.

[2] J.Inst.3.23.2, noting that Paulus’ view had been accepted by earlier, unnamed emperors.

[3] J.Inst.3.23.2-3; see also G.Inst.3.141 which recounts the same school dispute, seemingly before it was authoritatively settled.

[4] See R Zimmermann, The Law of Obligations: Roman Foundations of the Civilian Tradition (1990, 1996), 250-251.

[5] They were the subject of a short study by D Daube, “The Three Quotations from Homer in Digest 18.1.1.1 (1949) 10 CLJ 213, which mainly focuses on the mistranscription of Homeric texts in the compilation of the Digest.

[6] K Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (1944, 2024), especially ch 4.

[7] M Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (1972, 2004), especially ch 5.

[8] Il.7.472-475.

[9] See the Loeb Classical Library translation: A T Murray (trans), Homer: The Iliad, vol 1 (1978), Book VII at p 337; and R Lattimore (trans), The Iliad of Homer (1951, 1961), Book VII at p 180.

[10] Il.6.232-236.

[11] R J Cunliffe, A Lexicon of the Homeric Dialect (1924, 1963), 25.

[12] The exchange of armour between Diomedes and Glaucus was widely known in the Greek and Roman literature of classical antiquity. For a summary of classical sources, see W M Calder III, “Gold for Bronze: Iliad 6.232-36, in A L Boegehold et al, Studies Presented to Sterling Dow on His Eightieth Birthday (1984), 31-35. Some of the anthropological literature generated by the exchange will be mentioned in the second part of this blog entry.

[13] Ar Nic Eth V.9, 1136b.

[14] See R Lattimore (trans), The Odyssey of Homer (1965, 1975), Book I, 430 at 38.

[15] C M Kraay, Archaic and Classical Greek Coins (1976), ch 2.

[16] For a survey of the competing evidence and its interpretation, see R Lane Fox, Homer and His Iliad (2023), ch 15.

[17] M I Finley (B Knox (ed), The World of Odysseus (1954, 2002), esp xix-xxi and Appendix I.

[18] Il 23.702-705

[19] E R A Seligman (ed), A Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Book I, ch 4 (1776, 1910), 20.

[20] Il 1.309, 315.

[21] Il 2.449.