In the second of two-part posting, Professor Gillian Black (Commissioner, Scottish Law Commission and Chair of Scots Private Law, University of Edinburgh), Professor Nick Hopkins (Commissioner, Law Commission of England and Wales), and Nic Vetta (Legal Assistant, Scottish Law Commission) outline the Commissions’ joint proposals for a new regulatory regime for surrogacy in Scotland and in England and Wales.

Scots law, as it relates to the rights of children generally, has made significant progress in ensuring that the law places their welfare at the heart of all decision making, and recognises them as independent rights holders.

While encouraging progress has been achieved in relation to safe-guarding the rights of children, not least in terms of the rights recognised in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, some specific areas of the law do not adequately protect the best interests of the child. One example in the context of surrogacy relates to the current framework which exists for surrogate-born people to access information about their origins.

At present, people born through surrogacy can find out about their gestational and genetic origins in several ways, such as from their birth certificate, court files from a parental order application, or the existing Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (“HFEA”) Register of donor conception. (The HFEA register was set up in 1991. A separate voluntary Donor Conceived Register helps to connect donor-conceived people who were conceived before 1 August 1991 with their donor and any siblings born using the same donor’s gametes.) However, none of the current methods for accessing information about one’s origins were originally designed for use by people born as a result of surrogacy. As a result, there are gaps in the framework for surrogate-born people, and no clear route specifically for this group to access information. There are also inconsistencies in relation to access to information between adopted and donor-conceived people on the one hand, and people born via surrogacy on the other. As such, the current framework which exists for surrogate-born people to access information arguably falls short of Article 7 of the UNCRC, in terms of which the child has a right to “know… his or her parents”.

This can be particularly problematic since we know how important access to information is for children and adults, in terms of their sense of identity. Indeed, research shows that having access to information about the circumstances of one’s conception and gestation can contribute positively to the quality of relationships and psychological wellbeing within the family,[1] and that surrogate-born children value openness when it comes to information about surrogacy arrangements.[2] Further, the information may also be important for health reasons. Child Identity Protection (“CHIP”) and UNICEF have published a briefing note on children’s rights and surrogacy, emphasising the importance of knowing one’s own identity:

Knowing one’s origins is fundamental to the child’s physical, psychological, cultural and spiritual development. Having one’s own identity is also a gateway to the enjoyment of the child’s other fundamental rights, such as those related to protection, health, education, and the maintenance of family ties.[3]

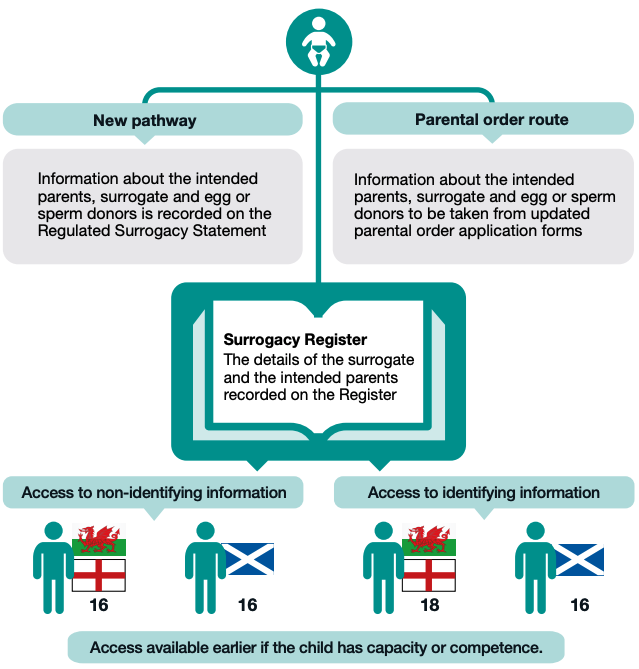

To address these gaps, we recommend creating a Surrogacy Register, to be maintained by the HFEA, alongside the existing HFEA Register of donor conception. The Surrogacy Register will record information for all surrogacy agreements entered into after the new law comes into force, whether on the new pathway or the parental order process, and whether domestic or international. The Surrogacy Register will provide a bespoke solution which makes it easier for surrogate-born people to access information about their origins.

We also recommend that surrogate-born persons may use the Surrogacy Register in to identify another surrogate-born person who was carried by the same surrogate, or to identify the surrogate’s own child(ren) – particularly to check if someone they are considering entering into a relationship with is genetically or gestationally related to them. Importantly, in all cases, information will only be shared if the other party has consented to their information being made available to other surrogate-born people, or the surrogate’s own child, as the case may be. In each case, the information can be made available whether or not the two people are genetically related.

We also make recommendations on the age at which a surrogate-born person is able to access the Surrogacy Register. In England and Wales, we recommend that a surrogate-born person should be able to access non-identifying information at age 16 and identifying information at age 18, or earlier if they are Gillick competent. In Scotland, people aged over 16 are deemed to have capacity under the Age of Legal Capacity (Scotland) Act 1991. For this reason, in Scotland we recommend that surrogate-born people will be able to access identifying and non-identifying information from the age of 16. If they meet a statutory test of capacity, they will be able to access both types of information under the age of 16.

Our recommendations provide a solution to the problems produced by the current system, in a way which both promotes the best interests of the child and is consistent with the children’s rights perspective. Proper recognition is now given to the rights of a surrogate-born child to “know… his or her parents” under Article 7, and to “preserve his or her identity… including family relations” under Article 8. This is complimented by our recommendations on the age of access which allow for flexibility and ensure the framework is participatory by incorporating the views and experiences of children.

What’s next?

Our recommendations – as contained in our draft bill – apply in Scotland and in England & Wales, subject to specific provisions in relation to matters such as parental responsibilities and rights, and succession, where we recommend surrogacy fitting into the existing Scottish provisions.

As surrogacy is a reserved matter, it is now for the UK Government to decide whether to introduce the bill, published with our report, giving effect to our recommendations. The Commissions’ view is that the reforms, if implemented, will improve outcomes for all parties involved in surrogacy and provide long overdue clarification and certainty to the surrogacy process as a whole.

[1] For a summary of these findings and list of empirical studies relating to donor-conceived and surrogate families, see S Golombok, We Are Family, (Scribe 2022), pp260-264; 274-280.

[2] K Wade, K Horsey, and Z Mahmoud, “Children’s Voices in Surrogacy Law: Preliminary Report”, shared prior to publication with the Law Commissions.

[3] Child Information Protection and UNICEF, Key Considerations: Children’s Rights and Surrogacy (February 2022) p 2. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/115331/file.