BAM TCP Atlantic Square Limited v BT plc [2020] CSOH 57 presents something approaching a full house of recent hot topics in conveyancing: interpretation of a deed of conditions; determination of the scope of common property; the transitional provisions in the Land Registration etc (Scotland) Act 2012; positive prescription and the offside goals rule. Lady Wolffe is therefore to be congratulated for managing to get through everything in a mere 95 paragraphs. The focus of this blog, however, is the interaction between inaccuracy as understood under the 1979 and 2012 Act, and the offside goals rule.

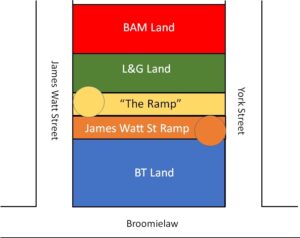

At its heart, the dispute was reasonably straightforward: it concerned the ownership of a strip of land between neighbouring properties and is an example of how much easier conveyancing cases would be for the reader if freer use were made of diagrams. With than in mind, a rather crude one has been attempted here.

The disputed land was an access ramp (referred to as “the Ramp” throughout the judgment) which lies between James Watt Street and York Street in Glasgow. The pursuer (BAM TCP Atlantic Square Limited) sought declarator that it was the sole owner of the Ramp. BT plc contended that it owned a one-half pro indiviso share in it.

The plots owned by the pursuer, by Legal & General Pensions Ltd, by BT and the two ramps shown in the diagram were all once part of a site owned under a single title by Pardev (Broomielaw) Ltd. In June 1997, Pardev registered a deed of conditions which (on Lady Wolffe’s interpretation, paragraph 43) defined “Common Parts” in a manner which included the ramps and indicated an intention that they would be owned pro indiviso by the plot owners. Plans were appended to the deed of conditions which illustrated that the ramps were part of the common parts of the site. Rightly, there was no suggestion that registration of the deed of conditions had dispositive effect. However, the disposition to BT (registered in July 1997) gave a bounding description of the BT Land and then included the following words “together with (1) the whole rights, common, mutual and exclusive pertaining thereto as specified in the Deed of Conditions granted by us in respect inter alia of the subjects hereby disponed”. This reference was repeated in the property section of BT’s title sheet.

The BAM Land was first transferred by Pardev in October 1999 and acquired by the pursuer in April 2002. The plan in the pursuer’s title sheet indicated that both the BAM Land and the ramps where owned by the pursuer. The burdens section included the Pardev deed of conditions, including the definitions which suggested that the ramps were to be owned in common.

Interpreting the titles

What then, did Lady Wolffe make of the titles? Was there a conflict between them and, if so, how was that conflict to be resolved?

First, she found that the 1997 disposition to BT had conveyed a pro indiviso right in the ramps. The pursuer’s argument that such a right could not be included because the ramps were outside the area described by the bounding description of the BT Land and (consequently) outside the area delineated in red on both the plans appended to the disposition and in the title sheet was rejected.

Lady Wolffe found that the words “together with (1) the whole rights, common, mutual and exclusive pertaining thereto as specified in the Deed of Conditions …” were sufficient to carry the pro indiviso share. In doing so, she rejected the pursuer’s suggestion that “pertaining thereto” restricted what the clause would carry to rights relating to property within the red boundary.

She gave (at paragraphs 54–55) a helpful account of the in interpretation of the term “pertinent” as used in Scottish conveyancing sources. This showed that that term frequently refers to rights beyond the boundaries of the principal subjects conveyed.

In light of this, the Keeper should have reflected the pro indiviso right in the title sheet. The question of whether the right was in fact reflected on the title sheet was crucial because, under section 3(1) of the Land Registration (Scotland) Act 1979, title flowed from the register. BT’s right was not mapped on the title plan. However, Lady Wolffe considered the reference to the “rights specified in” the deed of conditions and to its supplementary plans in the property section of BT’s title sheet, together with the deed of conditions’ inclusion in the burdens section of title sheet as sufficient. Thus, after registration of BT’s disposition, BT had a pro indiviso right in the Ramp.

The description and plan on the pursuer’s title sheet, on the other hand, included the ramps and made no direct reference to the right to the ramps being merely a pro indiviso share. The title plan did have an annotation referring to supplementary plans which were the same as those appended to the deed of conditions and the terms of the deed of conditions were included in the burdens section. Lady Wolffe held (at paragraphs 70 and 71) that, since BT’s right to the ramp was conferred by the disposition to BT rather than by the deed of conditions, mere reference to the material from the deed of conditions did not mean that the pursuer’s title sheet presented it as only having a pro indiviso share. The title sheets thus clashed.

Inaccuracy, voidness and voidability

As already noted, under the 1979 Act, title flowed from the register, i.e. the act of registration conferred the right. This gave rise to what was known as the “last-shot rule”: where there was a conflict between two titles, the more recent one would prevail since its registration operated to confer the right (and thus to divest the earlier title holder). The nemo plus rule is subverted.

As a result, the pursuer was the owner of the Ramp. However, the title was subject to a bijural inaccuracy. That is to say, registration had made the pursuer’s author the owner outright, but it ought not to have done so because, by the time that right was registered, a pro indiviso share had already been conveyed to BT. As it is sometimes put, the pursuer was the owner outright by virtue of “register law” but, as a matter of general property law, BT should have had a pro indiviso share.

This point is not reflected all that clearly in the pleadings or the judgment. Rather than arguing that, as a matter of general property law, the pursuer’s title was void, the defenders argued that it was voidable. In so doing, they reflected the usage in part 3 of the Scottish Law Commission Discussion Paper on Land Registration: Void and Voidable Title (SLC DP 125, 2004). The Commission observed, at paragraph 3.2, that “In principle, the 1979 Act, as interpreted, abolishes the category of void titles, for under a positive system of land registration all (or almost all) titles on the Register must necessarily be good (whether absolutely good or good but voidable).”

This terminology of voidability is attractive when discussing the operation of the 1979 Act because the term captures the idea of a bijurally inaccurate title being good for the moment. It is, however, quite dangerous because (as the Commission acknowledged at paragraphs 3.5–3.7), voidability in this sense is distinct from normal voidability. It is often problematic to have one word for two things.

Normal voidability is best analysed as a personal right to reversal of a grant. This explains the general rule which protects good faith singular successors and the fact that only certain parties (those holding the personal right) have the right to challenge a voidable title. (For further discussion of this, see J MacLeod Fraud and Voidable Transfer (forthcoming)).

A bijurally inaccurate title’s vulnerability to rectification is not presented in those terms by the 1979 Act. Under section 9(1), the Keeper was entitled to rectify an inaccuracy ex proprio motu, without regard to the wishes of the person in whose favour the rectification would operate. That is difficult to reconcile with someone holding a personal right. Further, the 1979 Act had no rule washing out the vulnerability on further transfer.

Furthermore, a title which is voidable in the normal sense does not result in inaccuracy either under the 1979 Act or the 2012 Act. The reason for this is quite simple: until it is set aside by a court, as a matter of general property law, a voidable title is good. Therefore, the register would be inaccurate if it did not show the voidable title.

Offside goals and inaccuracy

The argument made for the defenders regarding inaccuracy shows something of the risks associated with eliding voidability arising from the terms of the 1979 Act with normal voidability. Rather than presenting an argument based on the nemo plus rule, the defenders argued that incorporation of the terms of the deed of conditions into the burdens section put the pursuer and its predecessors on notice of the terms of the deed and therefore put them “in bad faith in the way explained in the Trade Development Bank [Trade Development Bank v Warriner and Mason (Scotland) Ltd 1980 SC 74] case and in Rodger (Builders) Ltd v Fawdry 1950 SC 483” (paragraph 85). Lady Wolffe accepted this and held that the title was bijurally inaccurate on the basis of the offside goals rule.

Two questions may be asked about this. First, would a breach of the offside goals rule render the title inaccurate? Second, is there enough here for bad faith as required under the offside goals rule?

On the first point, the answer is clearly no. The ultimate basis of the offside goals rule, as I have argued elsewhere, lies in fraud (see further J MacLeod, “The Offside Goals Rule and Fraud on Creditors” in F McCarthy et al (eds) Essays in Conveyancing and Property Law in Honour of Professor Robert Rennie (2015) 115 and Fraud and Voidable Transfer). Other rationales have been proposed (most recently, defective intention on the part of the acquirer: D L Carey Miller “A Centenary Offering: The double sale dilemma – time to be laid to rest” in M Kidd and S Hoctor (eds) Stella Iuris: Celebrating 100 years of the Teaching of Law in Pietermaritzburg (2010) 96). For a recent survey of the various theories, see N J M Tait “The Offside Goals Rule: A Discussion of the Basis and Scope” in A R C Simpson et al (eds) Continuity, Change and Pragmatism in the Law: Essays in Memory of Angelo Forte (2016) 153. None of them propose that the rule renders grants void rather than voidable. This, together with the absence of any suggestion of voidness arising from breach of the rule in the cases, suggests that breach of the offside goals rule results in voidability rather than voidness as a matter of general property law.

That being the case, until an action of reduction has been brought, a transfer in breach of the offside goals rule is good as a matter of general property law. The register would be inaccurate if it did not reflect it. Therefore, its presence on the register cannot be considered an inaccuracy.

On the second point, it is at least questionable whether notice of the terms of the deed of conditions was effective to raise an offside goals problem.

Despite the tensions arising from Trade Development Bank, where the offside goals rule was invoked by a security holder to set aside a lease granted in breach of one of the standard conditions, it is still generally accepted that the offside goals rule protects a personal right to a real right, or, as it was put in Gibson v Royal Bank plc 2009 CSOH 14, 2009 SLT 444 at paragraph 44, a right “of a kind potentially capable, in due course, of affecting these records in some relevant way.” Did the deed of conditions put the pursuer on notice of such a right?

The first problem with such a conclusion is that the deed of conditions did not, in and of itself, confer rights (either personal or real) on BT. Notice of the deed of conditions, by itself, would not tell the pursuer that Pardev had contracted to grant a right of the type envisaged. At minimum, it is necessary to say that notice of the deed of conditions, together with the knowledge that there had been dealings with the BT Land, put the pursuer on notice.

The second problem is with what the offside goals rule is intended to achieve. The point of the rule is to protect against frustration of personal rights in the gap between contract and grant of the real right. BT’s personal right to the Ramp had been discharged by performance when the pro indiviso share was transferred to it. At that point, there was nothing left for the offside goals rule to protect.

Allowing the rule to operate to protect real rights after their creation would mark a significant expansion of its scope and create an overlap with rules on good faith reliance in the land registration legislation. Such an overlap is undesirable because it creates the possibility for inconsistency and confusion without any obvious benefit.

The land registration rules strike a deliberate balance between dynamic and static security: on the one hand, potential purchasers need to be able to transact with confidence that they will acquire the rights they think they are going to get; on the other hand, too much protection for acquirers renders owners vulnerable to being deprived of their property. Allowing the offside goals rule to run alongside the land registration rules risks undermining this balance. In relation to personal rights, the offside goals rule fills a gap; in relation to real rights, there is no gap to fill.

For these reasons, the offside goals rule seems a dubious basis on which to conclude that a title sheet is inaccurate. Therefore, Lady Wolffe reached the right answer for the wrong reason. Pardev only had a pro indiviso share in the Ramp after it had granted a share to BT. According to the normal rules of property law, Pardev could, thereafter, grant no more than the remaining share. For that reason, a title sheet which showed it have granted full ownership of the Ramp was bijurally inaccurate thanks to the nemo plus rule. There was nothing in the 1979 to wash out the inaccuracy on further transfer. None of this depends on offside goals.

Transition and inaccuracy

While the registrations had taken place under the 1979 Act, the governing law is now the 2012 Act. Title no longer flows from the register and so the bijural inaccuracy and the distinction between “register law” and property law have been abolished. This mean that a rule was needed to deal with the bijural inaccuracies which were “in the system” when the 2012 Act came into force. At its heart the, transitional rule (found in paras 17 and 22 of Sch 4 to the 2012 Act) is quite a simple one. If, immediately before the designated day (8 December 2014), the inaccuracy could not have been rectified, paragraph 22 applies and it ceases to be an inaccuracy in any sense of the term. The effect of the transitional rule, is to make the register correct as a matter of general property law. If, on the other hand, the inaccuracy could have been rectified then, paragraph 17 applies: as a matter of general property law, the rights are modified as they would have been had a rectification taken place. The register is inaccurate in the simple sense of misstating the legal position and, once the inaccuracy and what is needed to rectify it are “manifest”, it can be rectified.

In this case, the register was inaccurate. The key question for Lady Wolffe, therefore, was whether the inaccuracy could have been rectified immediately prior to the designated day. The key provision dealing with that question was section 9 of the 1979 Act. Section 9(3) rectifications which would operate to prejudice a proprietor in possession were only permitted in very limited circumstances. The state of possession, however, was contested and therefore the matter could not be resolved without a proof.

Conclusion

The 1979 Act rules on inaccuracy were notoriously opaque and difficult to apply. No doubt many had hoped that they no longer held much importance. However, the transitional provisions in the 2012 Act mean that the ghosts of old conveyancing continue to haunt us for the time being. It is perhaps some consolation that, when faced with such problem it ought not to be necessary to try to deal with the offside goals rule as well.

John MacLeod, Senior Lecturer in Private Law, University of Edinburgh

(Many thanks are due to Dr (soon to be Professor) Andrew Steven for comments on this post.)