If you had to describe the Trossachs to a visitor who had never been there, but was familiar with England’s national parks, you might start by saying that it had the scenery of the Lake District, with the proximity to a major city of the Peak District. The geology is not really like that of the Lake district, it is metamorphic rather than volcanic, but the rock in both areas is old, hard and grey, resulting in a post-glacial landscape of craggy hills and long lakes.

Geological maps label the rock in the Trossachs as the Ben Ledi Grit formation. On close inspection you can often see the original bedding, warped into curves by the intense heat and pressure that caused the metamorphosis.

I was in the Trossachs because friends were staying in a holiday apartment there and had invited us over for a day. Everyone else went to avail themselves of the complex’s swimming pool, but I had failed to pack a swimming costume and thought it was too nice a day to be inside, so I sneaked out for a walk, taking the first path I found that left the road.

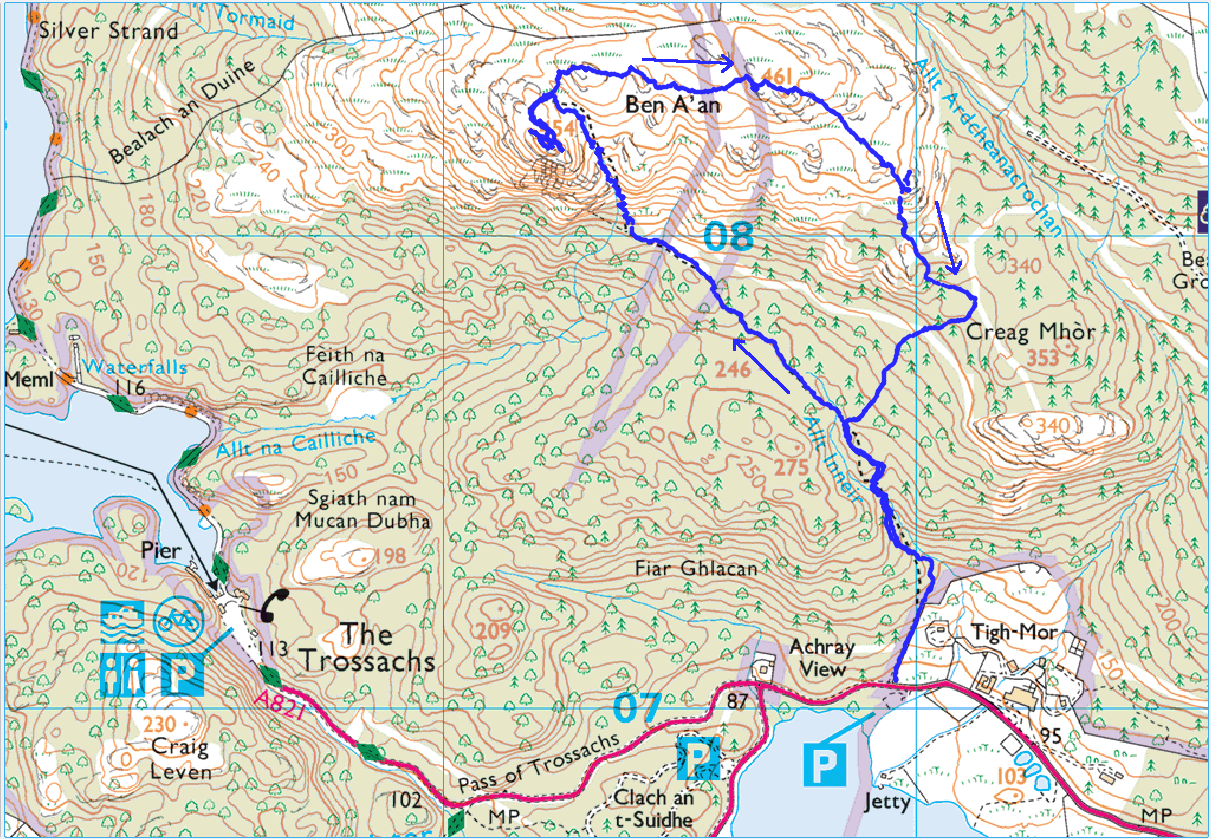

The path starts at a convenient car park and was labelled “Ben A’an hill path”; it was immediately obvious that it was a popular route and had been heavily engineered to protect the landscape from the erosion caused by a multitude of visitors. I found myself sharing the path with many other walkers, all intent on enjoying the pleasant weather; it had rained horribly the previous afternoon.

It is far less obvious from the start of the path where it is going, or why. The first half-kilometre ascends steeply along the valley of a small stream called Allt Inneir. As the path flattens out, the summit of Ben A’an comes into view about a kilometre away, the other side of a relatively flat area.

The area looks as if it was a dense plantation of sitka spruce until recently. Right now it looks like the aftermath of a protracted war. The trees appear to have been felled quite a few months ago; there is no sign of re-planting and I was moved to wonder whether the forestry commission intend to allow it to regenerate into a more natural sort of woodland.

The mountain itself has an attractive, pointy shape from this angle, and the stroll across the blasted heath does not take long. At the point where the tree felling devastation gives way to thin birch trees, rocks and heather the path steepens again; I and my many fellow travellers worked up a proper sweat on the ascent. The climb eases off near the top, as the path curves round the summit to approach it from the north west.

The view from the summit is an absolute treat, with Loch Katrine stretching away into the distance towards the mountains that surround Loch Lomond. Although you can not see it in the picture the distinctive shape of the Cobbler (a.k.a. Ben Arthur) is clearly visible to the eye. The view is, if anything, enhanced by the fact that you can’t see much of it until you reach the summit, where it is revealed to you rather suddenly.

The summit itself is a delightfully craggy, airy spot, and on a nice day you (and everyone else!) will want to stay there as long as possible. You might even catch a distant glimpse of the historic steamer, the Sir Walter Scott, as she chugs up and down the loch.

At 454m Ben A’an it is not large, but is a classic lump in every sense. (For others see here, here, and here.)

Although the underlying landscape is a bit like the Lake District, the upland ecology and land use are very different; there are a lot more heather and bilberry, and almost no sheep or dry-stone walls. Although the engineered path is very busy, there are no other obvious routes leading away from the summit. I do hate to return by the same route if there is an alternative, and it appeared from the map and my own observations that it might be possible to walk along the craggy edge extending east from the summit, and to return by a new path built by the tree fellers. So, after leaving the summit I headed east into the heather. Within five minutes I was completely alone and did not meet another person until I rejoined the main path.

The edge and its crags is interesting walking. The heather and tussocks make for slow going, and my towny shoes did not really provide enough ankle support. There are three or four little craggy summits to visit (and to enjoy having all to yourself) before the edge comes to an end. It is obvious why Ben A’an itself is the popular place to visit, though, you don’t get the view down Loch Katrine from any other point on the walk.

This is the view back towards Ben A’an from the last of the summits. From here I faced a slightly tricky descent to join the network of forestry commission tracks which (apart from a short hop across some blasted heath) took me back to the main path.