Depression Detectives is holding weekly Q&As, which are a chance for us to to quiz scientists and experts who work on depression or related topics. Last week we were joined by four scientists from Edinburgh University – brain imaging expert Heather Whalley and her colleagues Niamh MacSweeney, Miruna Barbu and Liana Romaniuk.

Q&A

Hi all!

Niamh: Hello everyone! My name is Niamh and I’m a 3rd year PhD student at the University of Edinburgh. My research looks at the biological, psychological and social risk and resilience factors associated with adolescent depression. I am particularly interested in how our brain structure and function is related to depression risk, and other social/environmental factors.

Heather: Hello – I am Heather. I am a Reader in Neuroimaging in Psychiatry at the University of Edinburgh. My research involves examining brain scans to look at depression, and looking at associations with various risk factors

Liana Romaniuk is here also – she is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with a background in brain imaging and can answer any clinical related questions

Miruna: Hi everyone! I am Miruna. I am a research fellow in the Division of Psychiatry at the University of Edinburgh. I study depression and its genetic risk factors, as well as how these relate to environmental variables. I also study something called DNA methylation , which is a process through which our genes can be “turned off or on”. I am trying to identify whether these patterns are different in depressed individuals as opposed to healthy individuals.

Depression Detectives Member C (DD C): Can you tell us in what way a depressed brain is wired differently to a non-depressed one please?

Heather: Good question! There has been a lot of research over several decades to try and work that out and we are only now beginning to understand. More recently there has been an effort to increase the size of imaging studies (10s of thousands of individuals) and they are highlighting some interesting and convergent findings. We are seeing decreased hippocampal volume (a region involved in emotion and memory), decreases in the cortex of the brain, particularly in regions considered to be involved in thinking/planning/reasoning. Decreased ‘healthiness’ of the brain’s connections (white matter), and altered functioning when the brain is at rest, and when it is performing certain functions. The disruption of connections, structure and function of the regions considered to be involved in emotion and reasoning are thought to underlie the core features of depression, low mood, low motivation etc.

DD C: Thank you. Have there been any studies looking at how this changes over time in individuals? It would be so interesting if there were a prospective cohort study in which well people were scanned at baseline the followed up over years and rescanned if they developed symptoms of depression to see how their brain had changed or if there were predisposing factors present.

Heather: yes – this is spot on! We are currently looking at a very large study based in the states that has scanned >10,000 9-10 year olds where they hope to follow them up over 10 years, and although their study isn’t specifically focused on depression – we in Edinburgh are hoping to study this exact point you have made.

DD C: So good to hear that you can study this on such a large scale.

Heather: also we and others have conducted very similar studies in the past (although in the 100s, not 1000s!) for those at high risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder who were well when recruited, and we then followed them with repeat scanning over 10 years.

DD C: That sounds interesting. Is the picture for people with bipolar disorder similar to those with depression? I do wonder about whether the depression experienced by people who only go low is the same entity as in those who swing between high and low.

Heather: actually in the study we conducted above that I mentioned, the majority of the young people that developed an illness in the bipolar high risk sample actually developed depression in the first instance. In this case it is difficult to know whether this is just the typical manifestation of bipolar in such a young group – or whether they would go on to just have low mood. We are actually following these people up using healthcare record linkage to try and tease this apart. Note: ‘high risk’ here refers to familial risk factors, and study participants were not told they were in the high risk group.

DD C: It would be interesting to know whether being told you are high risk for bipolar or depression makes it a self-fulfilling prophecy!

Heather: Ah – i could have worded that better – familial risk and of course we were v sensitive

DD C: I am sure you didn’t do anything to harm your study participants! I was thinking more about it in the real world, rather than the lab setting.

DD I: This feeds into the current diagnostic arguments about bipolar illness, particularly the concept of the BP spectrum. With regard to depression/bipolar, many are diagnosed with depression as the presenting symptom but are later diagnosed with bipolar. Depression by its nature is often the more distressing feature of bipolar illness. GPs who are the first port of call are poorly equipped/resourced to differentiate the subtleties of bipolar illness and therefore wind up treating the depression. If as some believe this can exacerbate bipolarity, it reinforces the need for better diagnostic criteria and skills in general practice. This in turn exposes the relative poverty of available treatment (especially in children and young people) both drug and psychotherapy. We could then venture into the minefield of over/under diagnosis/treatment of mental illness. It all underlines the desperate need for better diagnosis and treatment/therapy. Bring on the day when mental illness is diagnosed by a blood test.

Heather: Yes absolutely! It also speaks to the difficulty in diagnosing young people at early stages of illness, not just depression and bipolar disorder.

DD S: Can you tell us a bit about what brain imaging can tell us about what happens in depression?

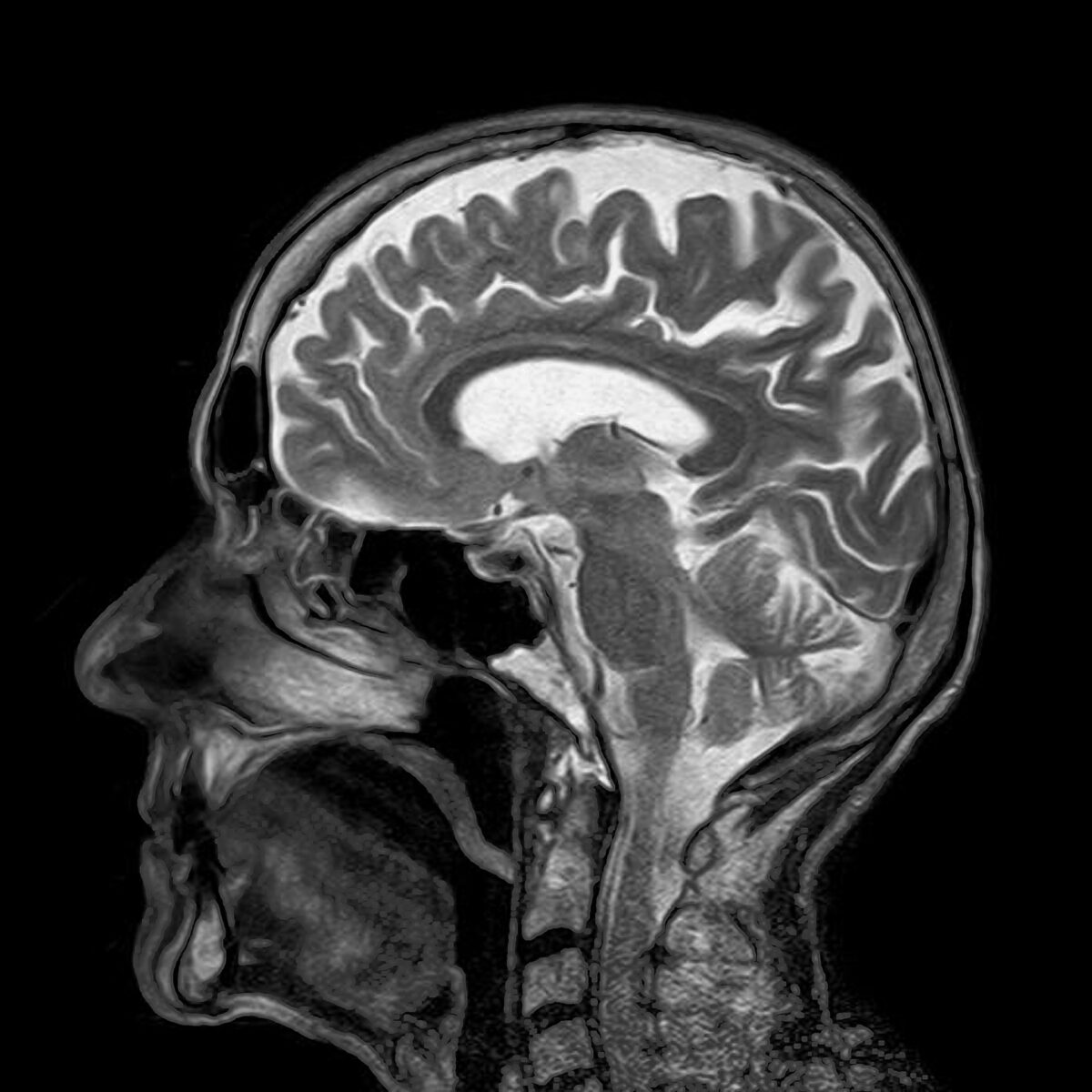

Niamh: Brain imaging is a relatively new technology, which means that it has really allowed us to expand our knowledge of how the brain works and differences that may occur in mental health conditions like depression. At the moment, brain imaging research looks at patterns in brain structure and function, such as brain volume as well as white matter tracts, which connect different brain regions, to see if we can identify whether there are differences in people with and without depressive symptoms. We need really large samples (thousands of people) to answer these research questions but thankfully in recent years, there have been lots of large-scale brain imaging studies that have greatly developed our understanding of depression.

DD S: What kind of things can you actually see with brain imaging? Are you seeing that some brain structures grow or shrink? Or are you seeing which bits are active or inactive?

Niamh: Good Q! It’s a bit of both actually depending on what your research question is. In terms of brain structures “growing or shrinking”, we can only see this if we use multiple data points over a period of time, which is known as longitudinal data. Further, we are looking at brain changes at what is called a group level – so on average across a large sample of people. With the development of large scale studies, it will be really exciting to look at how brain features change over time, especially in adolescence, when there is so much happening in the brain anyway. In terms of brain function, we do a special kind of brain scan, called a functional MRI (fMRI)- this allows us to look at what parts of the brain are “active” when a person is performing a certain task or just at rest. For example, we are currently running an fMRI brain study where we are looking at what parts of the brain are active when a young person with depression is irritated. To study this, young people are asked to read irritating scenarios in the scanner and imagine they are in that situation. We are then going to use data analysis methods to see what parts of the brain are active.

DD S: You said the ideal would be a longitudinal study. Can you use brain scans done for another reason as your baseline, to compare across time? To get ‘before and after’ pics? eg if someone has had an MRI for another medical reason, and then later gets depressed.

Niamh: This is a super Q and very relevant to large scale health research at the moment. There’s a lot of debate currently on whether researchers should have access to routinely gathered medical records to get a better overall picture of someone’s health, and then also to use any pre-existing health data (e.g., an MRI scan). This question is particularly pertinent because often the people that take part in research studies are not representative of the population at large. Research participants are more likely to be women and from higher socio-economic and education backgrounds. If we had access to health records, we may be able to include people who don’t have the time/opportunity to take part in research, and this would hopefully give us a better picture of whatever we are trying to study. However, lots of the population-based studies do try to combat this bias by recruiting as diverse a sample as possible but this can often be difficult.

DD C: Somebody in this group earlier asked if a depressed person’s brain changes with treatment (whether that be medication, exercise or talking therapy)? And can depression really, physically be ‘cured’?

In regards to the size of the hippocampus in depressed people. Does this show signs of improvement with treatment? Or are these people’s hippocampus already smaller? Predisposing them to depression?”

Very nice to be here – and again a great question. What we don’t really know as a field as yet is whether the brain changes that we see in depression are a cause of the illness, or actually a consequence of having the illness or medication. This is because most large studies are conducted in adults in mid-late life, and they tend to only capture a snap-shot of an individual. What we need to understand these features is what is called longitudinal data (collecting data from an individual at several time points over illness and treatment). Also, what we are interested in is imaging young people before they become ill in order to address the question as to whether the brain differences happen before illness onset, or after. This is important to know if we are thinking of being able to predict those who are vulnerable to illness, or to understanding pathways to illness, what happens during illness, and for developing novel treatments – or to targeting treatments to an individual.

DD I: In the previous Q&A there was a discussion about the difference between adult and adolescent depression. Can that difference be seen in brain imaging or methylation?

Liana: Absolutely: there’s definitely a lot of overlap in the symptoms adults and adolescents with depression experience. There’s some evidence to show that adolescents are more sensitive to being rejected by their peers, and tend to be more irritable – above and beyond what plays a normal part of adolescence. In terms of treatment, similar medications are used for both age group, although we’re especially safety-conscious with younger people, and so use a smaller range of tried-and-tested medications. The psychological treatments are crucial, and carefully adapted depending on the age of people we work with.

Heather: as a follow on – we are currently conducting a study to look at irritability in adolescent depression – during a functional imaging scan.

DD I: What is the difference between a ‘functional’ imaging scan and a normal one?

Heather: There are different types of brain imaging – we focus on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (though there are others for example that are used clinically like CT, or for other types of research like PET) – a functional MRI scan like I mentioned above allows us to look at which regions of the brain are ‘activated’ by a task or question. (this is actually due to a really cool quirk of nature related to the fact that oxygenated and deoxygenate blood have different magnetic properties). Other types of scan allow us to look at things like brain volumes of different regions (structural scan) -or allow us to look at the brain wiring (white matter – called diffusion imaging).

Niamh: Really interesting Q. We’ve recently done some work looking at whether the differences in brain structure we see in adults with depression are the same or different in adolescents with depression. We do indeed see similarities between adult and adolescent samples. For example, compared to people without depression, both adolescents and adults show a decrease in brain volume as well as impairments in white matter tracts/connections, especially in areas relating to emotion/thinking processes. However, we do see some differences too — adolescent depression was associated with lower brain surface area, a finding that we don’t see as commonly in adults with depression. This suggest that these changes in brain structure may be present early in the disease course of depression, and may be linked to the emergence of the disorder. However, as Heather mentioned, we only looked at a “snapshot” of depression and brain structure in these young people, i.e., we only had access to data at one timepoint. We really need to look at brain imaging data over multiple years, especially before the onset of symptoms, to really understand how brain features relate to depression, and what features are a cause or consequence.

Liana: This is really exciting because it’s quite novel within the field.

Miruna: In terms of DNA methylation, this field is very novel, especially in terms of associations with depression. In our department, we are trying to identify DNA methylation differences in adults, and we have identified some differential patterns that could add to our understanding of depression. Studies of adolescents have definitely shown DNA methylation differences, although large-scale studies are needed to determine if these are similar to those differences in adults. DNA methylation is also something that changes a lot throughout life as a result of environmental factors, so patterns in adolescence may not necessarily be the same as patterns in adulthood.

DD I: So things that we experience/do can alter our DNA methylation pattern?

Miruna: Yes, that’s right. For example, smoking greatly alters DNA methylation patterns. Smoking is also known to be associated with depression (smoking may increase your risk of being depressed) – so it is possible that one route through which smoking increases this risk is through changes in DNA methylation patterns. This is just an example, but DNA methylation plays a big role in other lifestyle factors as well, such as alcohol consumption and body mass index.

DD I: And if someone stops smoking?

Miruna: This is quite interesting – studies show that peoples’ DNA methylation patterns go back to looking like those of non-smokers, although this happens over years. In relation to depression – we have yet to understand whether depression risk is lowered as a result of this change (although quitting smoking is sometime tied to starting healthier activities, such as exercise, which increase well-being and are protective factors against depression).

DD N: Do you know if you can look at what’s happening in the brain and see a difference in activity in the same person when they’re depressed and when they aren’t, as opposed to changes in the structure of the brain?

Niamh: At the moment, we are quite far away from being able to detect changes related to depression on an individual level — i.e., having a brain scan to diagnose depression. This is because there are so many other factors related to depression risk, such as genetics and environment. Also, the development of large scale brain imaging studies will allow us to map out what “typical” brain development looks like across the lifespan — kind of like creating a growth chart brain development. Only then will we be able to identify divergences away from “typical” development, e.g., towards mental ill-health. However, it is very unlikely that we will just be using one factor to determine risk and resilience for depression — using a combination of factors will give us a much better picture.

DD S: Can I ask a basic sort of question, what techniques do you use? What exactly are you looking at?

Liana: One of the major techniques we use is magnetic resonance imaging – MRI – which is a fantastic way of taking detailed 3D images of structures like the brain, and has the added bonus of using no radiation, although it is pretty noisy! Its an amazing application of physics, where strong magnetic fields are used to align all the water molecules in our body, then other quickly-changing magnetic fields gently “flip” those molecules, and when they relax back to the centre, they emit a radio signal that we can detect. Different body tissues emit different signals, so we can reconstruct all these to generate 3D images. And if we do that quickly, and key in on signals associated with shifting oxygen levels, we can see the effects of changing brain activity over time.

Our top-notch scanners can take a detailed picture of your entire brain every 1.5 seconds at the moment

DD S: Wow!

DD J: If there are differences in a depressed person’s brain, could there be a screening programme for depression, like there is for cancer?

Miruna: Really good question! At this moment in research, I believe we are quite a long way from having a “brain-based” screening test for depression. This is because what we are observing in our studies are associations between specific changes in the brain and depressed individuals. Association alone will not tell us whether a person will definitely be depressed or not based simply on brain morphology. Moreover, apart from differences in brain, there are a number of other factors that may signpost whether an individual will actually become depressed (for instance, environmental or genetic factors). However, there is work going on at the moment to identify whether the function of these brain areas are different in depressed vs healthy individuals, and I think this field is making great strides, especially in adolescent research. I think in future, once we identify more definite risk factors for depression, we may be able to have a screening test for depression and be able to identify signs early on.

DD S: When you say ‘association alone’, is it possible that some people have those brain features and aren’t depressed, and other people are depressed without having those brain features?

Miruna: Hello! Yes, it is – as you say, some individuals may have brain features that resemble those of depressed individuals and vice versa. However, in our studies, we apply statistically-robust tests, so we can say with confidence that at a general population level, our associations are “true”. When it comes to an individual screening test, individual differences such as the one you mentioned may lead to someone being classed as depressed when they may not be. This is why studies often talk about replication, which refers to independent groups of researchers obtaining the same result multiple times – to make sure the difference is really there!

DD C: Is there any relationship between the areas of the brain affected in depression and those involved in memory? I find I struggle to remember things from the times when I was having a serious bout of depression, as opposed to everyday background levels when I was able to keep functioning.

Heather: yes, the hippocampus – one of the most commonly reported regions identified by many many studies, is thought to be involved in emotion and memory particularly. Though the thoughts at present are the depression isn’t likely to be due to a problem in one brain region in isolation, but a network of regions not interacting as they should. Emotion and memory of course are also v strongly linked. Events that illicit an emotion will usually be more strongly ‘encoded’ and remembered.

DD C: so if you are struggling to feel any emotion, for example in dissociative depression, then you may not create such strong memories?

Heather: Yes- well put! Though it is difficult to know which direction this might work in, in depression.

Liana: Just to add to that, we also know that memory encoding is very dependent on having relatively steady attention and concentration (which are processes drawing from broad brain networks). Sadly having disturbed concentration is one of depression’s more debilitating features, and that definitely goes hand in hand with the sense of not being able to remember things.

DD I: Sleep is also important for memory? And affected in depression?

DD C: ah yes, I forgot that 😂Excellent point. Is there a reason behind the disturbed concentration?

Liana: Ah, sweet irony! Concentration is a process that really does engage large portions of the brain’s cortex, as well as the deeper structures that coordinate activity around the brain – several structures and neurotransmitters play an important role, and its probably why concentration can be affected by many illness.

Sleep is also really important for “consolidating” memories – taking those experiences of the day, which are represented in a temporary way, and converting them into more robust memories by changing the structure of brain synapses.

DD C: Would you say that changes in volume in the different areas could be caused by the way people think? Asked the other way around: Can therapy potentially change the brain in a positive way?

Heather: I think that we just don’t know the answer here, there just aren’t enough large scale good studies to say for sure. There is a literature that has looked at differences in the brain between people experiencing a current depressive episode versus those that have recovered – or don’t currently have symptoms – but it is still unclear. Studies aren’t converging in a convincing way (I would say) – others may like to chip in here

DD I: Do different types of depression lead to different changes in the brain?

Niamh: We don’t yet know really but this is definitely a hot topic in depression research! Depression can present itself in many different ways and is often referred to as a “heterogenous” condition. We should be able to answer your question soon as more large-scale studies become available 😃

DD N: That’s all we’ve got time for! Thanks so much for coming Niamh, Heather, Miruna and Liana.

Liana: It’s been a really pleasure – the questions were all excellent and insightful!

Miruna: It was a really great experience! Thank you so much for having us – the questions were great!

Niamh: Thanks everyone for the great questions! Really interesting discussion 😃

Heather: I hope that has covered most of the questions – happy to answer anything outstanding offline. That was great fun – thanks to everyone for organising /asking qu and answering! Its really invaluable as researchers to think about all these questions (and new ones) in a different way. Thanks for having us!

DD C: Thank you all – such an interesting experience although it just makes me come up with more and more questions……