As part of Depression Detectives, we’re holding weekly Q&As with scientists and experts who work on depression or related topics. Our Q&A last week was with Mark James Adams, a statistical geneticist from the University of Edinburgh.

Q&A

Hi Mark!

Mark: Hi, everyone. I’m a researcher in the psychiatry department at the University of Edinburgh. My background is in computing, genetics, and psychology. I mostly work with population health datasets doing genome-wide association studies (abbreviated “GWAS”), where I look across the whole genome to find parts of our DNA that increase or decrease the risk of having depression.

Depression Detectives member E (DD E): Can the symptoms of depression lie dormant, for eg teens/adulthood then manifest at say 40 due to change of life and hormonal imbalance?

Mark: Yes, we do see differences like that. Some people seem to be at risk for having depression but have not yet experienced a life event stressful enough. For example, childbirth is a very stressful time for many people, especially mothers.

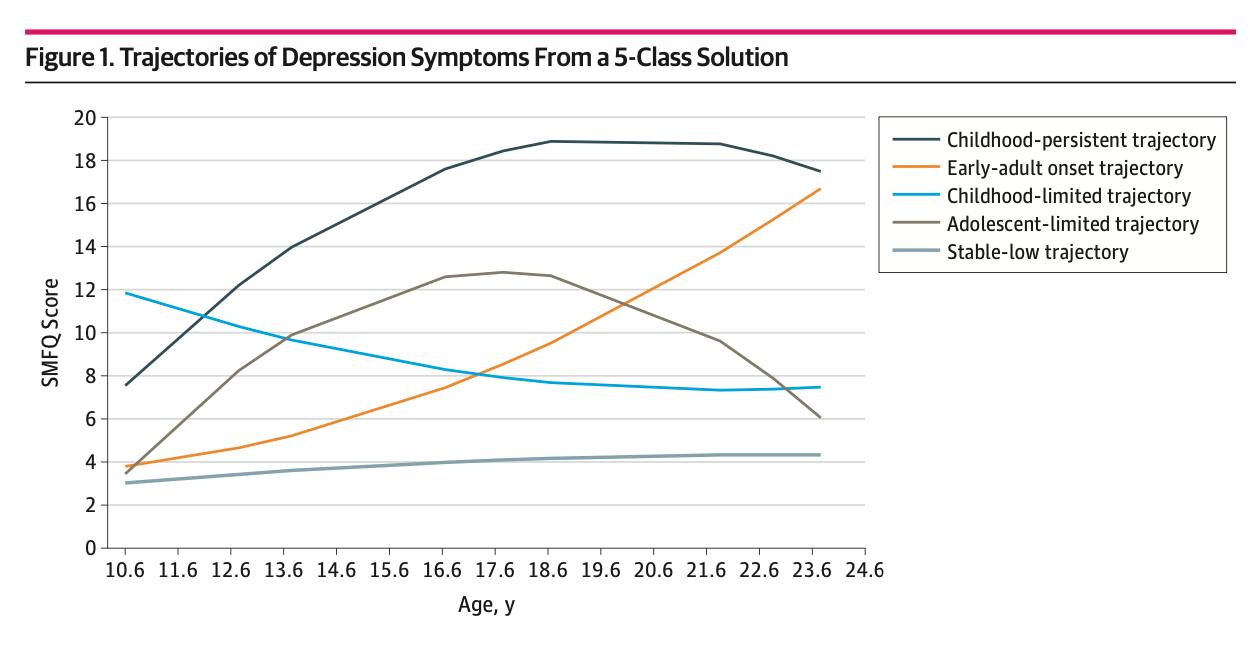

Here is a figure from a paper by one of our researchers showing different trajectories of depressive symptoms from adolescence to adulthood. The higher the number in the figure, the more depression symptoms a person has, and each line represents a different trajectory that the burden of symptoms can take.

DD N: Do most people who experience depression fall into one of the groups on the graph?

Mark: Yes, the “stable low” trajectory is the most common, followed by the “early-adult onset” type. The “childhood persistent” was the least common.

DD M: That childbirth can be a very stressful time is in itself rather depressing!

DD S: I feel like becoming a parent is the really stressful thing…!

DD M: both? 🤷♀️

DD S: Yes, both I guess. And on top of childbirth itself, the hormone changes are huge. But becoming a parent is an earthquake in your life that never goes away, if you know what I mean.

DD I: Being a parent means you are ‘always on duty’. No longer can you just go off for a walk for example.

DD A: Can you tell us about the kind of projects you’re working on at the moment?

Mark: My big project at the moment is part of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium to do a large genetic study of depression. https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/

One thing we have learned about genetics for depression is that each part of your DNA makes only a tiny contribution to making you vulnerable or protecting you, so it takes data from a very large number of people to identify those differences. In the study I am working on now, we are combining data from 3.5 million people from all across the world.

My other main project is a genetic study of symptoms of depression. Most of our data are just based on yes/no assessments of depression, so I want to see if there are genetic and environmental factors that influence specific symptoms. I have found that there is a genetic difference between somatic symptoms (like fatigue or changes in appetite or sleep) and psychological symptoms (like low mood or lack of interest in pleasurable activities).

DD S: That’s interesting. What portion of the risk is genetic?

Mark: About 30% of the differences between people is genetic, and about 10% is from differences between family environments.

DD S: I don’t know if this is within your remit to know, but how does that compare to other risks? I know we were talking in the group the other day about how big an influence poverty and precarity are. They seem much bigger than I had quite realised.

Mark: Yes, the genetic portion of depression is low compared to other psychiatric traits like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. In terms of genetic risk, depression is more like heart disease or diabetes. I think the environment is hugely important and we are still trying to find good ways to measure it, since what each person finds stressful can be very different.

DD N: How are the environmental factors measured at the moment? Or have they just not been studied much?

Mark: We collect lots of data on childhood experiences, strength of family connections, community involvement. This is from asking people about their lives, but we also pull in information based on where people live (for example, is there a lot of green space around).

DD S: So is it you, or colleagues, who analyses the rest of that data? I mean, if we wanted to find out if living near a chip shop affected your chance of getting depression, how easy or hard would that be to do? (Living near a chip shop is just a random example off the top of my head…)

DD I: Yes, if we chose a question like that, Mark Adams is the first person I would turn to!

DD S: Awesome. In that case, I have a lot more questions I’d like to ask. Can Mark come again?:-)

DD N: Really interesting about different symptoms having different genetic causes! In Stella’s Q&A she talked about the idea that maybe depression might not be all one illness but a group of different things, do you think that different symptoms having different genetic causes is evidence for that being true?

Mark: Yes, I agree with Stella. While there does seem to be something common genetically across all types of depression, there are probably differences that drive how depression is expressed as different symptoms.

DD A: Can you tell us what the GWAS is (in simple terms 🙂)

Mark: In every part of your DNA, you have two copies of each variant or gene, one from each parent. What we do is we pick one of the variants as a baseline, and then count how many copies of the other variant each person has. So for a simple 1 letter change in your DNA, there are usually two alternative variants, such as A and C. So the four genotypes are AA, AC, CA, and CC. If “A” is the baseline, then we count how many “C”s each person has (which will be either 0, 1 or 2). We then run a statistical test (called a “logistic regression”) that checks if people with more “C”s are more likely to be depression. We do this test for several million places in the genome and find which ones are robustly associated with depression.

DD S: If the genetic risk is relatively small, compared to other factors, why study it? Why not put all our resources towards, for example, relieving poverty?

Mark: There are a few reasons. One is just to understand the biology of depression. Even if the ultimate cause is in the environment, it’s the ultimate impact is in the body (how the brain reacts and overcomes stress, for instance).

Another main reason has to do with understanding causality. Did the poverty cause the depression, or did the depression cause job loss or breakdowns in relationships that resulted in poverty? With genetics, we know that the causal arrow always has to flow from DNA → Depression. We can use this to identify modifiable behaviors that can help alleviate depression. For example, this type of analysis was used to show that exercise really does help alleviate depression rather than the connection just being that people or aren’t depressed exercise more.

DD I: So maybe if we understand the biology, we might be able to intervene? (e.g. new drugs to treat or prevent depression) is that what you mean Mark?

DD S: Thanks Mark. That makes sense. But can you explain a bit more what you mean when you say this kind of analysis was used to show that exercise does alleviate, rather than depressed people exercising less?

Mark: The type of analysis is called “Mendelian randomisation” There is a good short Youtube video on it: The type of analysis is called “Mendelian randomisation” There is a good short Youtube video on it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LoTgfGotaQ4

DD M: What is it hoped these data might be useful for deriving?

Mark: I hope the data can contribute to finding treatments It would be useful to know ahead of time whether a person is more likely to respond to talking therapy or medication, for instance.

DD N: Is the difference between someone responding better to medication or better to talking therapy something you can see in the data currently?

Mark: We’re still looking into this. The limitation we are currently are having with our analysis is getting good data on talking therapy and how people respond to it. This is easier with medication since we can look directly at prescribing records to see if people are switching from one medication to another, or not filling their full course of prescriptions.

In some cases it might not be that the medication wasn’t working, but that the side effects were intolerable. So we hope to understand this better.

DD I: In the group it was discussed that people may move off medication and onto talking therapy (or something else) that they pay for privately.

Mark: I’m very thankful to this group for that insight. It will help our research tremendously.

DD S: Another tricky question. Are there any downsides to finding these genes? I mean, is it possible that in a future dystopia people selectively abort babies with depression genes? Or people with depression genes get denied health insurance, or whatever?

Mark: I’m much more concerned about implications for health insurance than designer babies!

One thing we know about genes is that they have influence many processes in the body. So tinkering with depression might have other consequences that we don’t know about yet.

The International Society of Psychiatric Genetics recently made a statement on the ethics of embryo screening: https://ispg.net/ethics-statement/

DD S: Like maybe the depression genes are useful for some things? Like sickle cell anaemia protecting people against malaria…

Mark: Yes, that’s what I’m thinking about. The genes can probably have a positive effect as part of the stress response. For example, rumination can be good if it helps you make a better decision or get out of a bad situation

DD S: So they remain in the population, because they are useful in small amounts, or certain circumstances. But if you have too many of them they can cause problems.

DD E: There is exciting news of a new DATAMIND national research hub being led by researchers/scientists based in England. How will this impact on MHSUs /researchers/scientists based in Scotland.

Mark: I hope DATAMIND helps Scottish researchers use data from England, where this type of project will have more of an impact since their data come from so many places. In Scotland everyone has a single unique identifier (called a Community Health Index number) that makes it easier to link our research participants’ data with their health records.

Mark: There was a question asked ahead of time about the DATAMIND research hub, which you can read about here: https://www.hdruk.ac.uk/helping-with-health-data/our-hubs-across-the-uk/datamind/

The background to efforts like DATAMIND is that the UK has a very long and rich history of health research studies where the same group of people are followed up over time. These started with birth cohorts in the 1940s and subsequent decades, which were set up to study health and social mobility. There is a lovely book about this history called “The Life Project” by Helen Pearson. https://helenpearson.info/book/the-life-project/

While these studies were hugely important, for decades they struggled with funding. It has only been in the last 10 years or so that their value has been widely recognised. DATAMIND is an effort to build on these research cohorts.

A similar project to see what these kinds of efforts are all about is Catalogue of Mental Health Measures. These research cohorts can look impenetrable from the outside, so one of the biggest barriers to using them is just being able to quickly see what kind of data they contain and to see how they can be used together (for example, I work with the Generation Scotland data set and it is useful to be able to see what other studies have similar measures of depression) https://www.cataloguementalhealth.ac.uk/

This catalogue is very useful for researchers, but my hope is that projects like DATAMIND can turn these resources into a dialogue between study participants, researchers, and the public. In Scotland we are fortunate that it is a lot easier to link between different data sets since, for example, we only have one NHS authority. I’m looking forward to DATAMIND so that we can also better use data from the other nations.

DD N: That’s all we’ve got time for! Thanks so much Mark, this has been really interesting!

Mark: Thanks everyone for the great questions!

Thanks Mark for answering my questions on symptoms of depression lying dormant through childhood/adolescence to menopause. Confirms my curiosity about this. Also the DATAMIND question that seems a vey exciting prospect to learn more about data science. I would also recommend Helen Pearson’s book on Life Project. A fascinating read about the basic beginnings of birth of cohorts right on up to the start of the Millenium.