To help us refine our final question into a small piece of research, last week we held a Q&A with three researchers who study depression and work with cohort studies. Alongside quantitative research using cohort study data, we’ll also be able to do research looking at the lived experience of Depression Detectives members, and this week we were joined by social psychologist and research consultant Petra Boynton, to help us figure out how to do that.

Q&A

Hi Petra!

Petra: Hello and thank you for inviting me! I’m a Social Psychologist and Agony Aunt and my work involves teaching other people to do research, or how to use it in their own lives.

Tonight my job is to help you all think of ways you can take your research forward, particularly focusing on some of the practical issues to consider and how to make that work useful for you.

If you’ve got any questions for me please ask!

Depression Detectives member E (DD E): Hello Petra, how do you begin to design a piece of research?

Petra: Thanks, that’s a great question! It really does depend. Sometimes research questions are very clear and from that it’s quite straightforward to design something. Other times people struggle as they have loads of ideas so aren’t sure which to pick or have one big idea that’s very difficult to fit into a clear research question. Conversations, reading, reflecting and endless cups of tea seem to be the main ways into designing questions 🙂

Petra: My opening question for you all is to find out about what you’d like to get from this research. Sometimes it helps with the planning to have noted your motivations, hopes and dreams for a piece of work.

DD I: Great question. In an ideal world, what would happen as a result of us doing this research?

Petra: I’d love to see with any research, large or small scale, that it makes a difference that those who were involved in the research can observe or benefit from. What would others in the group like to happen?

DD M: Ideally I’d like to see an improvement of practice if possible

DD I: So people go to the doctor every time?

DD M: Or don’t. Is there a way for a healthcare professional to check in with you rather than assume all is OK because you didn’t go back?

DD I: Good point. So the onus is not always on the ‘patient’?

DD M: Yes, but I feel it should be a 2 way process as well. Not so difficult to get an appointment if you feel you need one either.

With the necessary change to in person consults over the past year, is there anything that worked well and could be continued?

I appreciate it won’t always work, but providing more options must be better?

I can’t think how any of this links to our question though – sorry

Petra: It doesn’t have to link to your question currently. If your question is to explore the difference between self-reported incidents of depression and what’s on the patient records is once you’ve compared these you could begin to explore solutions, and make recommendations like you have done above (if appropriate)

DD E: Well the point of research is to improve services. In terms of this current piece of work, being a complete novice, I have found myself enjoying learning late in life more and more about mental health research, and it feels a bit like a jigsaw puzzle that slowly but surely it all fits together. Designing our own research therefore is the last piece of the jigsaw and another learning curve. The end result for me would be moderate changes to the mental health system.

Petra: That’s a great way of putting it. Pieces of the jigsaw puzzle are always important and it’s a better goal than trying to make an entire jigsaw! 🙂

DD E: I could do with more clarity on self-reported and health records. May not be appropriate for this discussion on designing a research study – are we all singing from the same hymn sheet?

DD I: That is a good point about definitions

DD C: If we wanted to do a focus group (by writing rather than talking within our Facebook group), what would you suggest we do to make it real research and not just a discussion? What are the processes of such research? How would we best analyse what people have written?

Petra: Text based conversations are very valid and rich, so really the key to making them more robust is to have very clear guidelines on what the group will be discussing, how to treat one-another, explaining about confidentiality and also listing what questions will be asked. From that the data is in some ways easier to analyse as it’s already transcribed – but you would need to check through it to note what is and isn’t going to be included based on what kind of qualitative analysis you’ve selected.

Christine: Thanks. What kind of qualitative analysis would you recommend for text-based focus groups, or which ones would you choose from?

Petra: It depends. I think people sometimes get confused with text-based data that it can’t be analysed in any of the many ways you could use for qualitative research. Often they believe only content analysis would be appropriate because the data is derived from text-based chat. However if you think about how focus groups are usually recorded then transcribed, the text based chat is cutting out the transcription, it’s presenting you with a transcript or script.

In that case your choice of qualitative analysis would be based on your research question and theoretical stance.

DD E: I’m interested in the question of anonymised data! Is it standard practice in academic research and what methods are used to obtain anonymised data!

Petra: It really varies. Traditionally social science research has anonymised data either by ensuring those in qualitative research are given pseudonyms and identifying information is removed. Or in the case of quantitative research people’s responses are collated in numerical data. However, in some areas of research people don’t want to be anonymous, they want to be heard telling their story. So that can introduce some interesting dilemmas for them.

DD I: As a reminder, our winning question is:

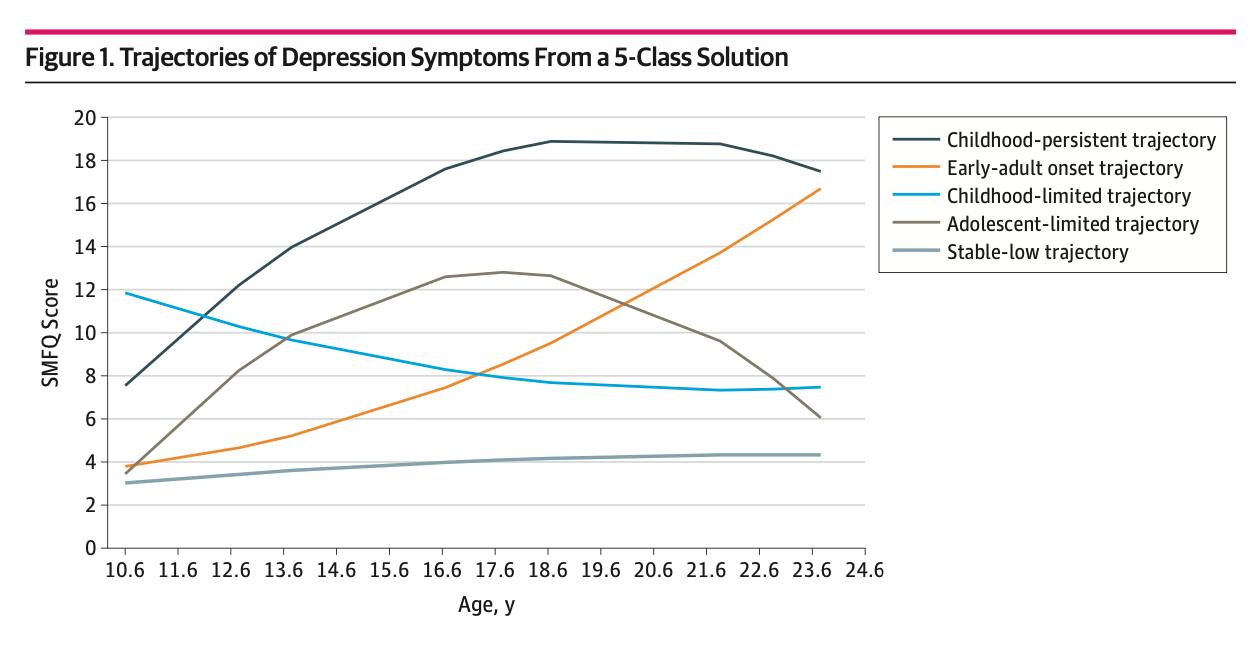

“How does chronic depression/dysphoria differ from, say a single episode, or discrete episodes of reactive depression? Are there markers (biological, psychological, behavioural, and current or in a person’s history, e.g. trauma) that distinguish them?”

But this is too wide to be a research question.

What defines a good research question for a focus group or survey?

Petra: It’s a fascinating area to begin with but I agree it is very wide. And in its current form it may not necessarily lend itself to either a questionnaire or focus group, so the question may need adjusting to suit the method. A good question for a focus group or survey to answer is one that is specific but allows people to reflect and share.

So in this case you could look at psychological and behavioural aspects through a survey and map that to medical history. A focus group would be more likely to give you lots of rich descriptions of living with depression so would again be useful but if you wanted to link that to chronic depression it would need a specific angle.

DD N: We’ve done some narrowing down in the group and it’s likely that our final piece of data research will involve comparing medical records to self-reported data in cohort studies, to see how accurate medical records are as measure of people’s experience of depression

DD S: But we were interested in why self-reported number of episodes might differ from what people’s medical records say. If people aren’t going to the doctors with some of their episodes, why is that?

DD I: The data science answer will be pretty dry (eg x% of self reports are recorded in medical records).

How might the group add richness to this?

Petra: Which would be really important to note and, I suspect very common. A focus group would let you explore the ‘why’ aspect to this. So why is it people’s medical records and self-reported episodes differ?

A survey might let people note how many episodes they have had where they did and did not go to the doctor, and what they did to self-manage if they did not go, plus their reasons for not going (e.g. couldn’t make an appointment, didn’t feel previous care helped etc).

DD M: I feel like I don’t know enough of what’s out there, to know what we don’t know! If you see what I mean

DD I: We also talked about private (paid for) options in the group.

Petra: The positive thing about the existing dataset is re-analysing it will explore things it hasn’t already done. Also it already exists as something detailed to interrogate. It’s assumed the records do accurately describe experiences of depression. It might be your research confirms this – but equally it may show that recorded incidents of depression are well-below what people experience you can make suggestions for improving care accordingly.

DD C: From the group’s discussion, there were some more specific areas that have come up as possible topics for focus groups or surveys, related to the question on single episodes vs recurring depression. Would you say some are more easy to do or more suitable than others?

– We could discuss if those with an experience of depression in this group have gone to their GP for all episodes of depression. If not, what did you do/ where did you get help if it wasn’t through the NHS?

– What made you decide what kind of help to seek? Which factors did the decision where to seek help depend on?

– Which episodes of depression did you seek help from GPs from – the first, a later one, all, the most serious, the one that you couldn’t link to situational causes…?

– How do people’s experiences of the help they received from the NHS influence their decisions to seek help when they have a relapse?

– How useful are questionnaires to measure depression, and how could that affect detecting single episodes vs. repeated episodes of depression? We could have a focus group discussion on a particular questionnaire and formulate/ highlight potential shortcomings from a bottom-up perspective, which might lead to a future review of the questionnaire.

Petra: – We could discuss if those with an experience of depression in this group have gone to their GP for all episodes of depression. If not, what did you do/ where did you get help if it wasn’t through the NHS?

This might be a useful discussion to have as a focus group as it would indicate the reasoning behind not seeing a practitioner, which you could incorporate into a survey that in turn you compare with health records.

– What made you decide what kind of help to seek? Which factors did the decision where to seek help depend on?

That could either be covered in a focus group or survey but it potentially is more closed (or you could provide a series of closed responses) so that could suit a questionnaire well.

– Which episodes of depression did you seek help from GPs from – the first, a later one, all, the most serious, the one that you couldn’t link to situational causes…?

Asking about when they did seek help is good, and again you could quantify this so they could indicate which ones they did (or didn’t seek help for). The problem you may experience is putting a timeframe on this and relying on people’s memories. So if you want to ask about this and map it to health records it will need to be as precise as possible.

– How do people’s experiences of the help they received from the NHS influence their decisions to seek help when they have a relapse?

I’d say this would be better as a focus group, although there’s also a lot of evidence particularly from experts by experience and groups like Mad Covid and Recovery In The Bin who have documented this. So instead of asking again it might be better to draw on that evidence?

– How useful are questionnaires to measure depression, and how could that affect detecting single episodes vs. repeated episodes of depression? We could have a focus group discussion on a particular questionnaire and formulate/ highlight potential shortcomings from a bottom-up perspective, which might lead to a future review of the questionnaire.

I think that could be very interesting, and it would match existing research that has criticised depression screening tools. However it would be quite time consuming to do well, so as a general discussion it might work but to extend it into research it might be more complex

DD M: What constitutes an episode of depression? Will this be defined?

DD C: Definitely something worth exploring! In the data science q&a we were told that it’s up to 2 years, but there was no answer as to who decided this and why it was defined that way.

Petra: That’s an excellent point, you would need to define this. And it may be you use an existing measure of depression to get this information.

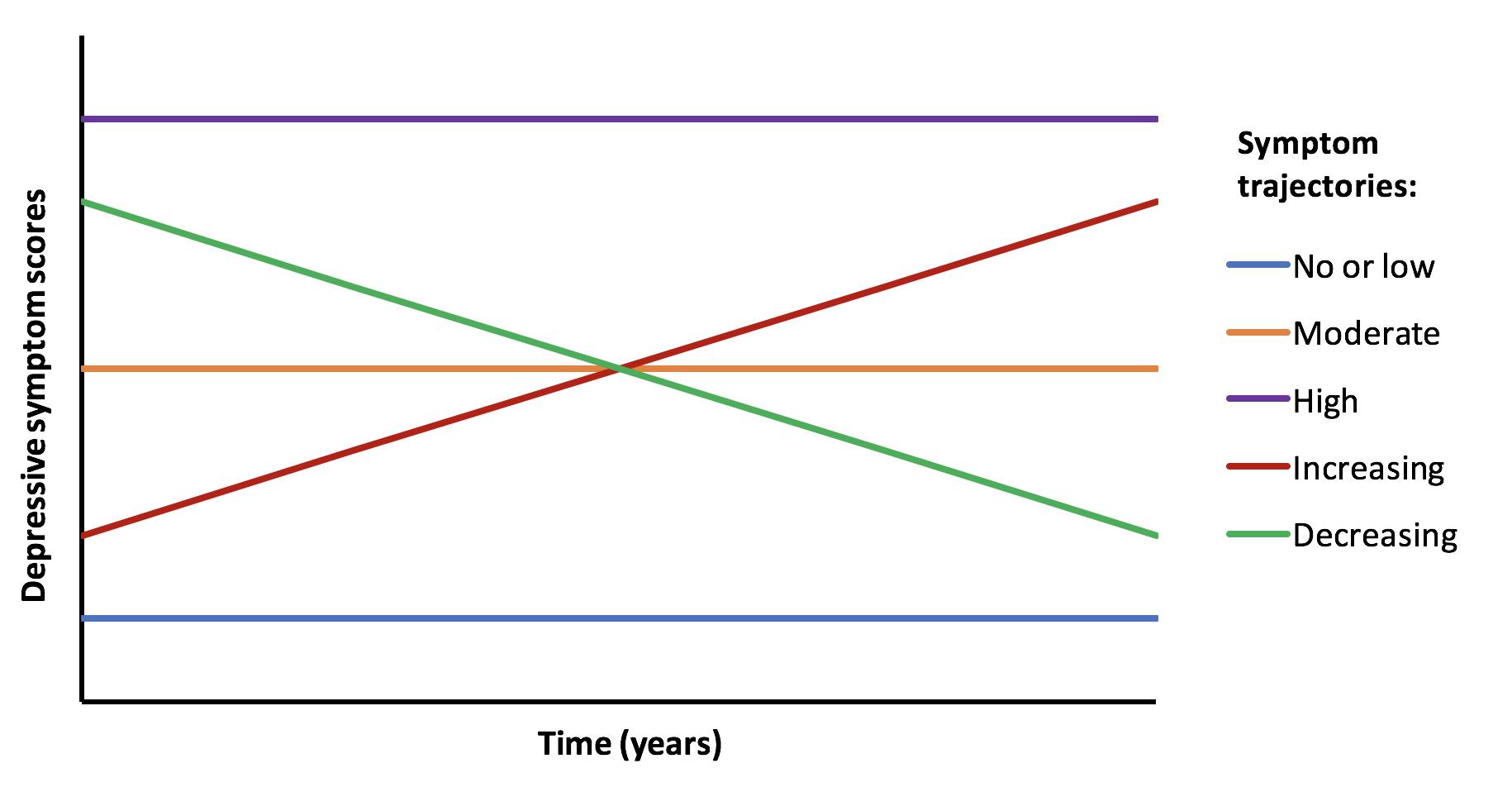

DD M: Yes there were 3 categories I think? So which type of depression would we want to focus on? I think this might help us narrow down the question

Petra: Something to think about is if you do the research if it could be criticised. People often panic about this idea as they fear it means their hard work being disrespected. What it means is whether other people might have questions or concerns about the research or notice barriers or limitations. In this case however you want to measure depression it would need to be something all participants understand and would respond to similarly. For example ‘major depression’ might be interpreted in many ways so you will need to define it for all.

Petra: If your plan is to Answer the question “Compare self-reported data to health records”. How might people think that would work in practice?

And as a follow up to this it might help to consider what you think the research might discover. My guess would be that self-reported data would suggest a far higher incidence of depression than what is on health records. But what other possible outcomes might there be? If you can consider these it will help you shape your question and how you’d like to answer it.

DD M: Petra, good evening and thanks for being here. What tools do you recommend for the analysis of qualitative data? Thanks

Petra: It really depends. Some people like to use qualitative data analysis software like Nvivo or Qualtrics, whereas other people do the analysis manually. If you don’t have a large dataset the latter may be a better option. I’d suggest if you plan on doing qualitative research then another session like this with a qualitative researcher might be good to help you think about ways to analyse and interpret your data.

DD N: We’ve got about nine minutes left folks!

Petra: I’m not sure if we’ve covered everything people would like to ask. But my advice would be if you want to compare self-reported episodes to health records you need to find a way to match self reported depression with what’s on a health record. But in a way that is robust and transparent.

For example people will know they are self-reporting, but if they already know what’s on their record they may over or under-estimate their self-reporting so how you present that information may need to be carefully managed.

You’ll need a clear measure of self-reported depression over a set period of time (to match the existing health record).

That sounds simple – to match self-report to the health records, but it’s surprisingly in-depth.

Once you know the direction the self-reporting corresponds with the health records you could run a focus group to explore the findings, what they mean, why you think they have happened in the way the research indicates, and what recommendations might be made for improving care.

DD N: That’s all we’ve got time for I’m afraid! Thanks so much for coming Petra, this has been really interesting – a lot to think about!

Petra: Thank you for having me! I always find these conversations leave us with even more questions so if after this evening you are still unsure or have other things you’d like me to answer please let me know and I can get you more information. I think this is such an important piece of work and I’m really looking forward to learning what you find out!