Having previously implemented a rubric in their course and written about their experiences, Brodie Runciman and Gary Standinger set out to use their rubric alongside samples of work to make assessment expectations transparent to students. They recently presented their practical ideas at the University’s Learning and Teaching conference in June 2025. In this blog post, they share their experiences, highlighting how these strategies contribute to effective assessment and feedback within Higher Education. Brodie and Gary are Teaching Fellows at Moray House School of Education and Sport, and teach on the on the MA Physical Education Programme. This post is part of the ‘Transformative Assessment and Feedback’ Learning and Teaching Conference series.

Making assessment criteria explicit

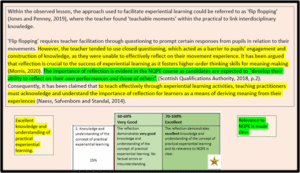

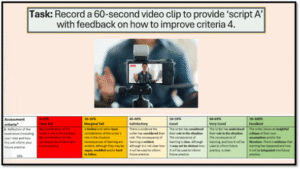

When assessment criteria remain unclear and unhelpful, this deprives students of the opportunity to take full responsibility for their learning. Well-defined rubrics, however, clarify grading expectations and emphasise the qualities of high-quality work (Brookhart & Chen, 2015). While we had already created a carefully designed rubric available to students on Learn, we wanted to take things a step further to maximise its effectiveness. By focusing on formative assessment learning activities with the use of the rubric, our goal was to help students better understand what was expected of them and prepare them more effectively for the summative writing task. We also wanted to support students in developing their evaluative skills. Encouraging self-assessment and feedback was crucial to shifting the assessment process from a one-way approach to a more meaningful, two-way dialogue. In doing so, we hoped students would become confident in using the criteria and more engaged in their learning.

Sadler’s (1989) seminal work on formative assessment identified three conditions for effective academic feedback:

- Understanding what good performance looks like;

- Being able to compare current performance to that standard;

- Learning how to improve to close the performance gap.

Sharing a clear rubric with students before a summative assessment is a helpful first step in setting out those standards for performance. That said, to better support learning, it is beneficial to take it a step further. When students participate in activities that help them explore and understand the assessment criteria, they are more likely to feel confident and less anxious (Kuhl, 2000). This type of engagement also encourages self-efficacy, improves self-reflection, and ultimately leads to improved learning outcomes.

Using samples of work with a rubric

Even with the benefits mentioned above, many students still find assessment criteria dense and abstract (Carless and Boud, 2018), making it difficult to interpret nuanced criteria descriptions. Often, the intended meaning behind the standards remains hidden, relying on teacher’s interpretations rather than being made transparent to students. One helpful learning activity is to use examples of student’s work. These samples can offer useful illustrations of what quality looks like at different levels, making the criteria easier to understand (Brookhart & Chen, 2015). In contrast to abstract lists, samples of work are user-friendly because they are more relatable and accessible for students (Carless, 2017). Engaging with samples of work helps students develop their ability to judge work effectively, supporting them in aligning their understanding with the expectations of the teacher, and in our case, the rubric. With a clearer understanding of each standard, students are better equipped to self-assess their current progress, provide themselves with meaningful feedback, and improvement to their work.

While Handley & Williams (2011) worry that students might copy from samples of work, the risk of plagiarising can be mitigated by designing learning tasks that differ from the sample or by using short excerpts instead of full texts. Providing a range of samples is also crucial, as it shows that quality can take different forms and is not limited to one model answer (Sadler 1989). Most importantly, using samples as a basis for discussions between students and teachers can bring real value. These conversations help to highlight what makes work effective and unpack the thinking behind teacher’s judgements. In this way, samples serve as a starting point for a deeper understanding of the assessment task, rather than just examples to copy.

Conclusion

Students are not always confident or equipped to judge different standards of assessment. Criteria can often seem vague, unhelpful, or difficult to interpret. However, we found that when we actively supported students in understanding the written criteria and developing their evaluative skills, a noticeable shift began to take place. Students started to move beyond relying solely on teacher feedback and began to take greater ownership of their learning through self-monitoring. Rather than remaining passive feedback receivers, they became active, confident feedback seekers, asking questions, regularly checking their progress against the criteria, and seeking clarification to help improve their work.

In our context, this demonstrated a clear change in how students approached assessment tasks. Feedback evolved from a one-way process delivered by the teacher into an ongoing, student-led dialogue. While our rubric and overall approach are by no means perfect, what it did achieve was to encourage more meaningful engagement with the assessment task and a clearer understanding of the standards. Ultimately, this supported students in becoming proactive, independent agents who generated and applied their own feedback to their work.

References

Brookhart, S. M., & Chen, F. (2015). The quality and effectiveness of descriptive rubrics. Educational Review, 67(3), 343-368.

Carless, D. (2017) Students’ experiences of assessment for learning. In Carless, D., Bridges, S., Chan, C & Glofcheski, R. (Eds.), Scaling up assessment for learning in higher education (pp. 113–126). Singapore: Springer.

Carless, D., and Boud, D. (2018). The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 43 (8), 1315–1325.

Handley, K., & Williams, L. (2011). From copying to learning: Using exemplars to engage students with assessment criteria and feedback. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(1), 95–108.

Kuhl, J. (2000). A functional-design approach to motivation and self-regulation. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 111–169). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Sadler, D. R. (1989) Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18, 119–144.

Gary Standinger

Gary Standinger

Gary Standinger is a Teaching Fellow at Moray House School of Education and Sport, and teaches on the on the MA Physical Education Programme.

Brodie Runciman

Brodie Runciman

Brodie Runciman is a Teaching Fellow at Moray House School of Education and Sport, and teaches on the on the MA Physical Education Programme.