In this enlightening blog post, Qingrou Zhao, a third-year history PhD student at The School of History, Classics, and Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, delves deeply into the concept of “rewilding creativity” through interdisciplinary teaching in tutorials. Inspired by ecological rewilding, which allows nature to reshape itself with minimal human intervention, Qingrou explores how educational methodologies can similarly benefit from reduced rigidity, enhancing creative and intellectual freedom. By bridging diverse academic disciplines, she advocates for a learning environment where theoretical and methodological boundaries are crossed, allowing students to engage with material in a richer, more connected manner. This post belongs to the Jan-March Learning & Teaching Enhancement theme: In-class Perspectives to Engaging and Empowering Learners

Stop Being Disciplined! In a recent PhD event at the Edinburgh Futures Institute, Dr. David Overend compared interdisciplinary research to the ecological concept of rewilding – a restoration practice that minimizes human intervention to let nature reshape itself. Sitting in the audience, I was struck by how “rewilding” perfectly captures an ideal form of interdisciplinary teaching, too. It hints at the richness of creativity that could grow among students when we cross theoretical and methodological boundaries. More importantly, it is a vivid reminder that academic disciplines are recent, artificial constructs.

At the School of History, Classics & Archaeology, faculty increasingly emphasise interdisciplinarity both in their own research and in teaching. As a PhD student in history, my own work blends quantitative and qualitative methods across economic and social history, global and imperial studies, and more. As such, interdisciplinarity comes across as something natural rather than something to be enforced. Theoretically, too, interdisciplinary teaching fits neatly with the structure of small tutorial groups: collaborative, student-centred environments should be ideal for interdisciplinary explorations.

However, having tutored on several interdisciplinary courses, I have observed how “border-crossing” can feel daunting to our students. For many, it implies a heavier workload and harder intellectual challenges: to learn about the Stonewall Uprising and the Indian Rebellion as a self-identified “British Medievalist”, to do maths and use statistical software as a humanities student, to speak with a wider audience and apply historical learning to today’s reality. This all feels a bit… much! Especially, for undergraduates new to any discipline, hearing about interdisciplinarity might feel like being thrown into a field without any farming tools.

But why do we need certain tools to engage with nature? Why should the exploration of interdisciplinarity feel intimidating in the first place? This blog post stems from my own experience rather than theoretical musings. The following mindset has proven helpful: teaching interdisciplinarity is not so much about actively encouraging students to break limits. Instead, it could be a passive process of ignoring pre-set limits that confine many established researchers, and empowering new students to “rewild” intellectual spaces with their genuine interest. Lectures may need to stick more closely to specific content, but tutorials can create an engaging, comfortable, yet stimulating environment for students to connect with broader contexts and sources, and answer questions that discard perceived boundaries in natural ways. The rest of the blog post shares two case studies of applying this perspective in practice.

Teaching History as Inquiry

The first case study involves breaking down methodological barriers. For the past two years, I have tutored on the course “The Global Economy Since 1750”. Designed for the MA History and Economics programme, it is open to all students interested in global economic history. The syllabus ambitiously covers regions from the industrial core to often overlooked regions like Africa and the Ottoman Empire, spanning pre-industrial times to the recent global financial crisis.

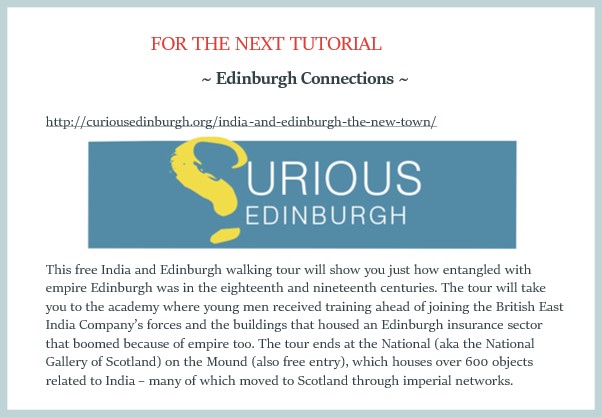

Perhaps more intimidating is the course’s methodological reach. It introduces students to quantitative history, or cliometrics, which has gained momentum over the past fifty years. Having many PhD friends who hate the sight of numbers and equations, I understand why students might feel overwhelmed. Are we really expected to learn three hundred years of global economic history in one semester – and do math as historians?

The first tutorial, “How to Do Quantitative History (Without Panicking),” tackles this concern. However, as the “pink elephant paradox” goes, saying “don’t panic” alone might actually heighten stress. Therefore, instead, I provide a brief history of quantitative analysis in historical study. Together, students and I discuss the question: How can numbers aid historical analysis? Must an economic historian always use quantitative methods? The discussion usually leads to a reassuring consensus: quantitative methods are one of many tools in a historian’s toolkit. As in statistics, “garbage in, garbage out”. Numbers are useful but only as relevant as the historical question demands. They are neither inherently better nor scarier than any other source.

Underlying this discussion is a message that the word history, in its etymological origin, meant investigation or inquiry. To navigate the sea of human experience in the past, one needs guiding questions, but not necessarily rigid boundaries. A historian can use maths, if necessary. To solve the puzzle at hand, texts, numbers, pictures and videos, a portrait, a vase, … , or biological discoveries tracing the pathogen of the black death, could all be relevant or irrelevant as sources.

“Look around, look around!”

Most, if not all of us, start our journey as undergraduate historians, sociologists, physicists, and computer scientists with genuine curiosity. Gradually, some will unfortunately get frustrated by specific methodologies and technicalities. University tutorials are therefore a crucial space to guides students – and tutors, too – to find question we are interested in answering, to guard our courage to go into the wilderness of knowledge, and to rekindle the instinct to use all methods and sources possible to answer the academic questions at hand.

The second case study thus involves crossing over broader, ontological boundaries. I believe university learning or any learning to be part of a long-term process of understanding and building connections with the world – with different spaces and across time. Therefore, in my tutorials, I hope students could see that the point of studying history or entering any “discipline” should never be closing ourselves up into a box of isolation.

This past September marked my second time tutoring on “The Historian’s Toolkit”, a first-year undergraduate course. The organiser of the course Dr Zubin Mistry actively encourages students to walk out of the classroom. We form students in each tutorial group into smaller “study groups” of three or four as a means of informal peer support for fresh undergraduates. Meanwhile, the course organiser maintains a weekly column called “Edinburgh Connections” on the Learn page. It identifies sites in Edinburgh that connects in some way with that week’s topic – which students can visit for themselves or in their study groups. I could really relate to the following paragraph they wrote for students:

History isn’t just done by looking at books. It’s embodied in lived environments and sculpted into urban landscapes. Visiting these places allows for a unique connection with the material, the city, and fellow students.

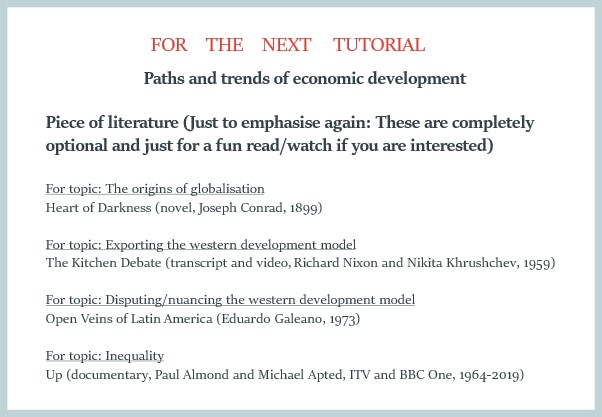

In addition to “Edinburgh Connections”, in all courses I tutor on, I usually provide my students with weekly recommendations for non-academic books, films, music, and primary sources that relate to the course material. For “The Historian’s Toolkit”. I call this feature “Outside the Kit”. I hope students could feel, in this practice, the feasibility of connecting everything they are interested in, every space they encounter – in person or online or on paper, and tools inside every traditional disciplinary kit, to the subject they are studying.

Finally, I constantly remind myself, as a tutor, to let go of temporal, spatial, and disciplinary provincialism, and not let “interdisciplinarity” become a new paradigm that constrains myself. Interdisciplinary teaching, like rewilding, should not be a didactive regurgitation of “you should let go of rigid boundaries” – which many undergraduate students do not yet have! Instead, an interdisciplinary tutorial passively yet powerfully passes on the idea, by opening the way for students to ask their own questions, find new directions, embrace many worlds, and set out on intellectual journeys of their own.

As Ryszard Kapuściński incisively reflects in Travels with Herodotus (a collection of non-academic essays that I believe should go on every global historian’s bookshelf!):

Herodotus travels in order to satisfy a child’s question: Where do the ships on the horizon come from? And is what we see with our own eyes not the edge of the world? No. So there are still other worlds? What kind? When the child grows up, he will want to get to know them. But it would be better if he didn’t grow up completely, if he stayed always in some small measure a child. Only children pose important questions and truly want to discover things.

Herodotus learns about his worlds with the rapturous enthusiasm of a child. His most important discovery? That there are many worlds. And that each is different. Each is important. And that one must learn about them, because these other worlds, these other cultures, are mirrors in which we can see ourselves, thanks to which we understand ourselves better—for we cannot define our own identity until having confronted that of others, as comparison.

And that is why Herodotus, having made this discovery – that the cultures of others are a mirror in which we can examine ourselves in order to understand ourselves better – every morning, tirelessly, again and again, sets out on his journey.

Qingrou Zhao

Qingrou Zhao

Qingrou Zhao is a third-year history PhD student at The School of History, Classics, and Archaeology. Her current projects broadly concern global and imperial history, migration history, children’s history, and quantitative history. Qingrou is passionate about teaching and interdisciplinary research – and the intersection of the two! At Edinburgh, she has tutored on undergraduate courses across the HCA and the SSPS, and she works as a tutor at the HCA writing centre. She was nominated for the EUSA Student Tutor Award in 2023, 2024, and 2025.