In this extra post, Professor Tim Drysdale and Dr Tim Fawns reflect on their attendance at a recent conference, “Excellence in teaching – The future of digital learning”, which debated issues of innovation, leadership, and resistance in the current HE climate.

We both travelled to Mainz to represent The University of Edinburgh for a two-day conference, “Excellence in teaching – The future of digital learning”, which was hosted by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU). This initiative was a collaboration between Universities Scotland and the German U15 university network (a kind of Russell Group equivalent), with the aim of each country learning from the other while strengthening our international ties. It was an interesting mix of formal and informal, structure and freestyle. It was also a mix of high profile (e.g. Ministers Jamie Hepburn, Clemens Hoch and Jens Brandenburg; Georg Krausch, President of JGU and Chair of the U15; industry leaders, etc.) and those a bit further down the food chain (e.g., us).

This conference was another moment in a long history of connection between Scotland and Germany in relation to rapid, major educational change. At the end of the enlightenment, in the early 1800’s, while the Germans introduced laboratory work—demanded by students—into the formal science curricula, the Scots resisted change. Among other things, this led to a shift in European leadership in chemistry education. Would the same be true this time around, when the upheaval is digitalisation?

On our first evening, we walked around Mainz, admiring the small city’s variety of aesthetics. This included a very attractive new bridge, the Zollhafen Mainz bridge, with dazzling lights that seemed to call out for us to walk across. On reaching the other side, we found an industrial wasteland. Well… in reality, it led to a site in the early stages of construction but for the purposes of this story, it was a Bridge to Nowhere. It was an analogy for technological change that is insufficiently attentive to the values and needs of educators and students; that is shiny and appealing but does not take us where we need to go. This tension—between making cool things and pausing to first generate a clear sense of what needs to be made, why, and how it fits with both the bigger educational picture and the localised considerations of teachers and learners—ran through the conference, popping up in many presentations and side conversations over coffee, lunch and dinner.

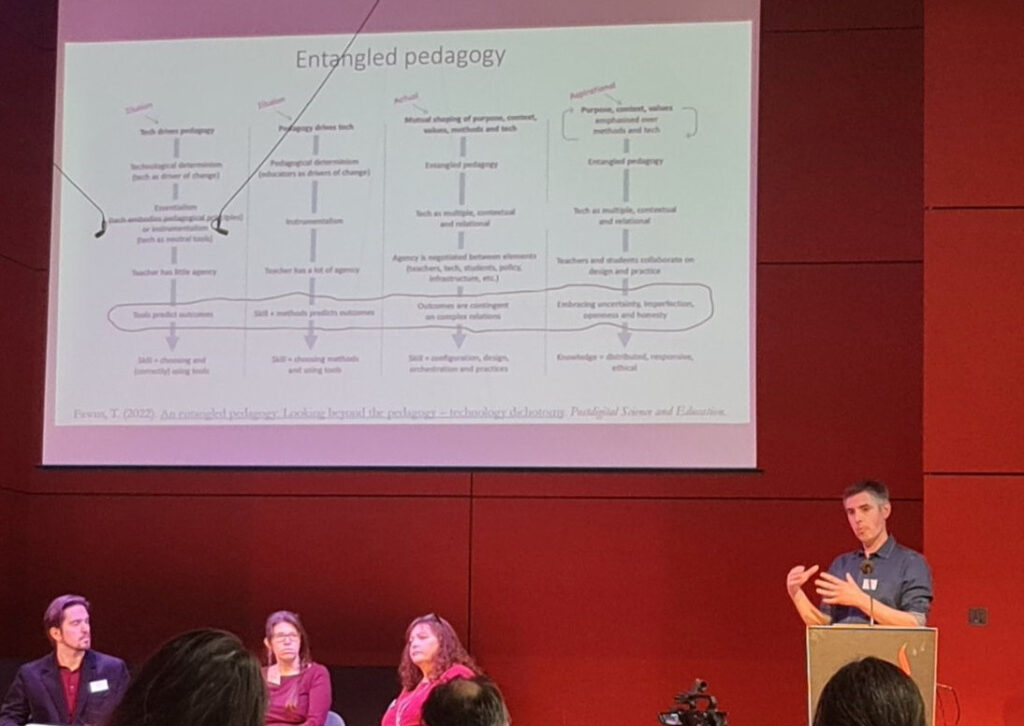

In his presentation, Tim F made the point (which featured prominently in the closing address of the conference) that people typically do not resist all change, but specifically “this change.” Perhaps, they are not ready to take that particular step, or do not understand why they should take it. Perhaps they are, themselves, an innovator, and the step does not go far enough. Resistance is not to be overcome by management dictat because technology can’t just be forced into educational practice. It must be integrated into what’s already there: infrastructure, other technologies, cultures, traditions. This is not simply a good idea; it’s an inevitability. The Resistance is not a group of people but the friction that is necessarily present during technological change.

Fortunately, each country and institution conveyed a fine-grained picture of innovation, leadership, and resistance. In his talk, Tim D argued for treating technologies as collaborators rather than human-replacements. Commercial technology often constrains creativity.

For us, open-source digital tools and infrastructure are most suited to academic values of creating and sharing (new) knowledge that is inclusive, diverse, transparent, and modifiable. An open-source model can help our global community avoid duplicating everything just to make a small change to suit local cultural variations. At the same time, there are clear benefits to working together across institutional and national boundaries to attain critical mass to create and sustain the digital tools and infrastructure necessary to make the pragmatic possible.

There was a sense, across the conference, that we should not attempt to go back to how things were but go forwards while carrying important lessons from the pressurised and chaotic responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet there was also acknowledgement of the challenge of predicting the future, heightened by the uncertainty of our present times. Rather than rushing into technological solutions, most at the conference advocated a nuanced approach where human relationships and values underpin choices about integrating technology into our educational ecosystems.

This is a massive challenge that will take collaboration in the development of new forms of knowledge. A lot of staff will be exhausted from the pandemic but for some staff, innovation has always been part of their practice and will continue to be. The University of Edinburgh draws on a rich heritage of digital education activity, and we need some people to experiment not just with practice, but also with physical and digital infrastructure. Given the scale of the challenge, we also need to work beyond our institutional borders, e.g. with our U15 colleagues. Waiting until we absolutely must make change, as we did with the pandemic, highlighted the human and organisational cost of last-minute adjustments. Expanding our culture of ongoing innovation might feel risky, but the time and effort is a crucial investment in developing a knowledge base that will help us take nuanced human-centred approaches to an uncertain, digital, future.

Both Tims thank Prof Colm Harmon, VP (Students), for supporting our attendance at this event.

Tim Drysdale

Professor Timothy Drysdale is the Chair of Technology Enhanced Science Education in the School of Engineering, having joined the University of Edinburgh in August 2018. Immediately prior to that he was a Senior Lecturer in Engineering at the Open University, where he was the founding director and lead developer of the £3M openEngineering Laboratory. The openEngineering Laboratory is a large-scale online laboratory offering real-time interaction with teaching equipment via the web, for undergraduate engineering students, which has attracted educational awards from the Times Higher Education (Outstanding Digital Innovation, 2017), The Guardian (Teaching Excellence, 2018), Global Online Labs Consortium (Remote Experiment Award, 2018), and National Instruments (Engineering Impact Award or Education in Europe, Middle East, Asia Region 2018). He is now developing an entirely new approach to online laboratories to support a mixture of non-traditional online practical work activities across multiple campuses. His discipline background is in electronics and electromagnetics.

Tim Fawns

Tim Fawns

Dr Tim Fawns is Deputy Programme Director of the MSc in Clinical Education, and also leads a course on Postdigital Society for the Education Futures programme in the Edinburgh Futures Institute. He is also the director of the international Edinburgh Summer School in Clinical Education. His main academic interests are in education, technology and memory. Recent publications include:

- Fawns, T. (2022). An Entangled Pedagogy: Looking Beyond the Pedagogy—Technology Dichotomy. Postdigital Science and Education.

- Fawns, T., Aitken, G., Jones, D. (Eds.) (2021). Online Postgraduate Education in a Postdigital World: Beyond Technology. Cham: Springer.