In this extra post, Majdouline El hichou, Research Assistant on the PTAS-funded project on ‘Co-Creating a Development Needs Analysis (DNA) for PGRs’, shares insights into the co-creation process, learnings from surveys and focus groups, and their implications for the new DNA. You can read more about the origin of the PTAS project in this blog post by Anna Pilz, and please do check out the project webpage.

I joined the ‘Co-Creating a New Development Needs Analysis (DNA)’ project team within the Institute for Academic Development in April 2024 during the initial project phase of evidence-based empirical research. My role has entailed designing and facilitating surveys and focus groups among postgraduate students and supervisors according to participatory and adaptive methodologies, as well as data analysis and leading on the creation of our DNA toolbox.

Participatory methodologies

As Postgraduate Researchers (PGRs) and supervisors are the main users of a Needs Analysis, we wanted to understand the challenges and shortcomings of current approaches to Training Needs Analyses / Development Needs Analysis (used here as TNA/DNA). How could we increase engagement and usefulness of DNAs, based on students’ and supervisors’ experiences and practices? The element of co-creation is central to the project, from inception to data collection and trial implementation.

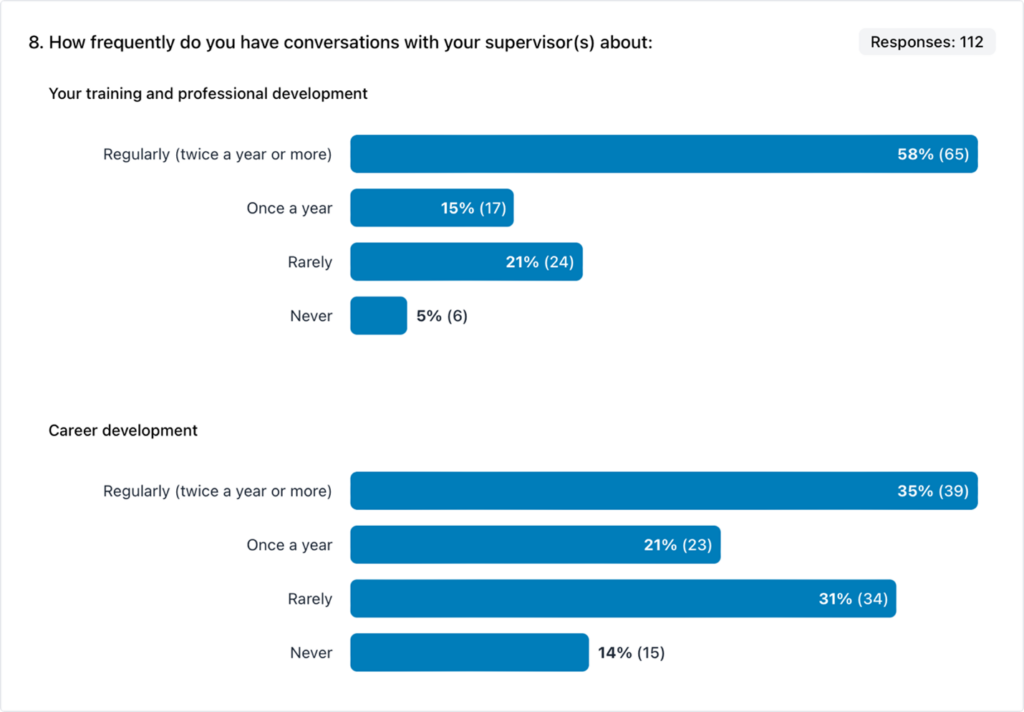

The anonymised surveys allowed us to gather honest insights as well as recruit participants to the focus groups that allowed for in-depth discussion of initial findings. The surveys ran in spring 2024. We received 112 responses from PGRs and 60 responses from supervisors from across the University. Our student respondents offered a good spread among those who were in the beginning / early stages of their PhD journey (33%), at the middle stage (38%) or in the final phase (29%). One of our questions aimed to give an understanding about the frequency of conversations with supervisors about training and professional development on the one hand, and career development on the other:

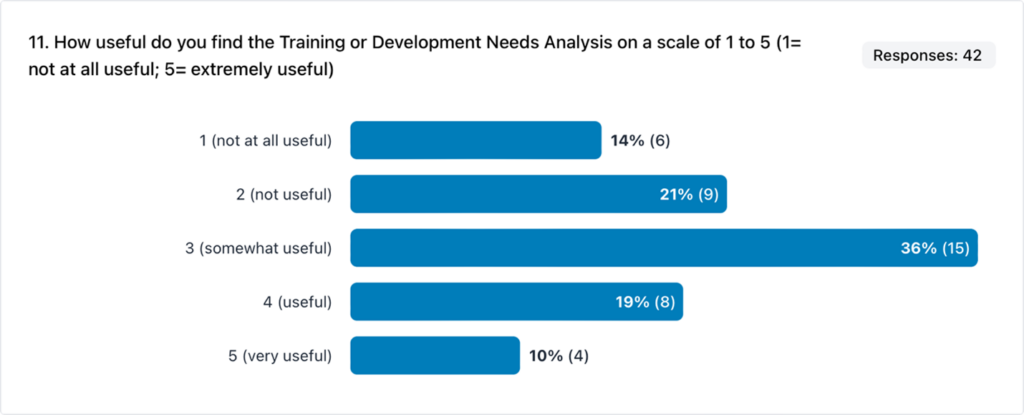

When asked whether they are familiar with a TNA/DNA, 38% responded with ‘yes’ and the graphic below indicates how these 42 students perceive the usefulness of the form / worksheet:

For comparison, 68% of responding supervisors have more than 8 years of supervisory experience, 22% have between 3 to 8 years’ experience, and 10% of respondents have less than 3 years’ experience. Corresponding to students’ unfamiliarity with a TNA/DNA, 75% of supervisors signaled that they are currently not using a TNA/DNA in their supervisions and 92% did not receive any training or guidance for engaging with such frameworks.

Challenging the deficit model of development

Whilst varying in experience, we noticed very strong parallels between PGRs and supervisors’ relationship to the use of existing TNA/DNA. For example, one of the key limitations to engagement is that the form often feels like a tick-boxing exercise that students are mainly encouraged to engage with at the beginning of their PhD and then, at times, during their Confirmation Panels. This not only turned their DNA into a passive process but also didn’t always allow for honest reflection.

“The main lightbulb moment for me was realising that it is to my advantage to identify gaps in my knowledge, skills or experience, since this understanding to be used to leverage access to exciting, useful or desirable training. Training doesn’t have to be a chore.”

(PhD student survey response on benefits of using a TNA/DNA, University of Edinburgh, 2024)

The current deficit model of TNA/DNA was highlighted in both surveys and focus groups. Based on our data collection, we really wanted to challenge this deficit model and encourage students to start their reflection from the point of what they have already achieved, what skills and experiences they are entering the PhD with. And this includes highlighting their career stage at the start of the PhD rather than assuming every student starts from the same point, whether that is age, career progression, goals, and/or disciplinary background.

“As a mature student, I am doing my PhD part-time whilst working in an established career. Therefore, career development conversations in my case are different from what they would be like for other students. They are, nonetheless, ongoing explorations for me.”

(PGR focus group response – University of Edinburgh 2024)

A student-centered approach rooted in intentionality and access

For many, the whole process felt quite dehumanising. It not only triggered a lot of anxiety for students who might be unsure about their career paths and what their subsequent development needs are, but also and most importantly did not make any space to reflect on personal development. This was a crucial point for us to address as many participants felt that a focus solely on PhD-related development needs did not allow for reflections on how personal circumstances – may it be mental health or elements of lived experiences – affected their development needs.

In this sense, students felt that DNAs assume a one-size-fits-all career pathway both in terms of staying in academia and research-related careers. Often, this leads students to not feel ownership of the form as it mainly contains what training they think they are expected to complete as part of their course, rather than including their very specific interests and considering the needs that might emerge from their individual pathways.

This has influenced our approach to co-creating the DNA where the very structure of each activity allowed space to reflect in a multi-layered and non-linear way about development needs. To allow for intentionality and tailored reflections, we frame the reflections in separate but overlapping sections: PhD related; career at large; and personal development, as well as making space for various career pathways and distinctions between necessary and desirable skills.

“I see myself as supporting students who are finding their own paths. They lead the conversation by indicating their career intentions, and I aim to follow through by directing them to relevant activities, institutions, and people.”

(Supervisor’s survey response on their role in identifying students’ professional and career development needs, University of Edinburgh 2024)

Ecosystem thinking for holistic developmental support

Another challenge that both students and supervisors flagged is that the whole process of defining one’s development needs seems solely focused on the supervisor/supervisee relationship. Sometimes students count on the supervisor to figure out their needs for them and how to go about achieving them. For those students who have less proactive supervisors when it comes to professional and career developmental conversations, they may feel disadvantaged.

To tackle this issue, one of the central components of our DNA toolbox is the “Creating your DNA ecosystem” activity that encourages students, once they have reflected on their specific development needs, to build their own tailored ecosystem. This is based on the questions: “what do I need support with?”, and “who is the right person/group/service to offer that support?” This allows for wider developmental support beyond the supervisory team, extending into peer communities, other departments or services, industries, research groups, as well as lived experience communities.

By curating their DNA ecosystem, students can equip themselves with the right team to help them achieve their goals and navigate challenges without solely counting on their supervisors. It will also allow supervisors to be candid about what they can and cannot offer support with and recommend alternative people/services accordingly to be added to the student’s DNA ecosystem.

Based on these findings, we’ve established a DNA toolbox that includes:

- ‘Creating your DNA’ activities document that features visual prompts rather than text-based questionnaires or tables. The form operates in a non-linear manner, so students can start or end with any section they feel most comfortable with.

- Handbook for PGRs with additional prompts and resources for those unsure where to start with the activities document.

- Supervisor guide with insights, prompt questions, and signposting to further resources.

With the academic year 2024/25 under way, we’re excited to trial our draft DNA as well as the Handbook for PGRs and a Guide for supervisors in our two pilot communities – in Precision Medicine and in the School of History, Classics and Archeology. In addition, we’re gathering feedback from participants in our university-wide focus groups. We hope that the co-creation of this DNA toolbox will allow for greater engagement from both students and supervisors and will serve as an anchor and roadmap to student’s development.

If you’re a PGR student or supervisor and interested in the drafts and would like to shape the resources, please get in touch with us.

Majdouline El hichou

Majdouline El hichou

Majdouline El hichou is a transdisciplinary researcher, educator, facilitator and artist, currently a second-year PhD candidate in Human geography at the University of Edinburgh. Her research and practice centers processes of autonomy-building, community development, Indigenous and embodied knowledge systems, decoloniality, and liberatory pedagogies. As a facilitator and consultant, she has extensive international experience in human rights, capacity-building and policy development both within education and cultural institutions as well as governmental and non-governmental organisations. Her expertise is grounded in participatory and trauma-informed approaches, decolonial and anti-racist education, disability justice, and adaptive and arts-based pedagogies.