Jared Taylor, programme director for Animation at Edinburgh College of Art, explains how pedagogical aspects of creative disciplines can help promote resilience in students…

Most, if not all, creative disciplines necessitate a certain resilience in their practitioners. Audiences can be wayward and fickle, critics can instil terror, the manual labour involved can be protracted and arduous, the use of emergent technology can engender a fear of not being quite current enough, and the perceived value of the creative industries at a governmental and societal level is often contested. Within this context, the brave or the foolish who choose to study Animation are the ones who will come to depend upon their resilience more than most.

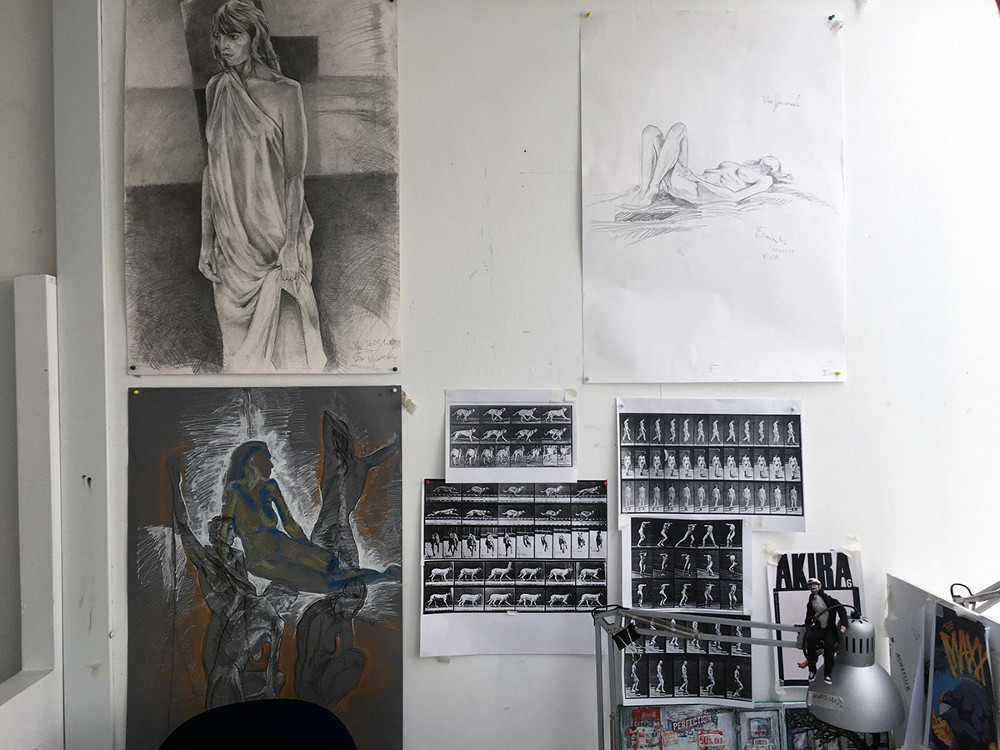

The pedagogies we employ in the Animation studios at Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) to help develop resilience in our students consist of three key areas: diversity, experimentation, and pragmatism.

Diversity

Diversity in method, content and style are aspects that, as lecturers, we value very highly in the work of our students. Given the rapid flux and dynamic nature of most commercial projects, employers within the creative industries also greatly appreciate diversity. This can be a hard concept to sell to a group of students who have come straight from secondary education with its culture of exams, league tables and a rigid binary notion of correct and incorrect. It sometimes manifests as a desire in our students that we show them how they animate “in the industry”, or a suspicion that there is a universally applicable and appropriate method of animating that will somehow mark them as “industry ready”. Chris Colman (Dreamworks) tells our students: “Whatever you do when you apply to Dreamworks, don’t show us a portfolio that makes it look like you work at Dreamworks. We have lots of people here who already do that, what we need is something different.”

Some of our courses require the students to employ multiple methods of production to provide a variety of solutions to the same narrative problem, while other courses require our students to hybridise methods such as CGI and physical puppetry.

Experimentation

All worthwhile experiments bring with them the potential for failure, and this gives students the opportunity to learn methods for coping with the next failure, and to acquire contingency planning skills. Failure isn’t something that many of our students welcome, and we have been surprised by what our students see as a failure. For some, failure is defined as a result that is anything less than perfect, or anything that is slow to develop, such as mastery, or confidence. Samuel Beckett’s quote “Fail, fail again, fail better…” is something of a catchphrase in the studio.

We hold that experiments should also be rigorous, and iterative. This notion is fundamental to one of the projects that we run each year in conjunction with students from the Reid School of Music’s MSc Composition for Screen programme, and animators from NBU and NATFA in Bulgaria -10X10X18 . Animators and composers work to complete a film or a score in 24 hours. They repeat this process for every working day in a two-week period, culminating in 10 completed films, in 10 working days. This experience runs contrary to the students’ expectations about how time-consuming animation is to produce . While some of these films are not at all “good”, some are fantastic demonstrations of what can happen when you just jump in and see what you can make happen. This project goes a very long way to helping our students divest themselves of the need for perfection, and any preciousness about what they make.

Pragmatism

Our version of pragmatism centres on our scavengers’ policies of working within our means, and of repurposing technology that we find, for example, we built a render farm with 160 cores using computers that were going to be thrown out. Pragmatism underlies our decision to encourage students to choose tools rather than worship them. We don’t want our students to be operators of software, defined by their knowledge of an application. We want them to understand their relative merits, and bend them to the service of their films.

This understanding of resilience has taken a little time outside of the Animation studio at ECA to coalesce. Mayra Hernandez-Rios, a graduate from 2014 who was one of the animators responsible for this year’s Oscar nominated Loving Vincent, reflects:

Very very thankful to ECA, to all of you, for everything. I can’t say how wonderful it was for me to be there. I thought ECA gives you much learning about initiative, creativity and perseverance. In my experience, it has been more in touch with the professional world, as that is what you need to continue growing.

Vera Babida, now animating in Australia, recently talked to ECA Alumni about her experience of the Animation programme.

The qualities of resilience that we hope to develop in our students are also the sort of qualities that we as academics need to thrive in a habitus that is as defined by its perpetual change as it is by its endless cyclic repetition. Oh, wait a minute… that sounds a bit like animation…