In this post, Frederik Dahl Madsen and Kay Douglas examine their experience with a new approach to assessment feedback, and how it could empower the students as autonomous learners, and enhance the student voice. Frederik is a PhD student, and Kay is a Outreach and Widening Participation coordinator. This posts belongs to the Student Voice in Practice series.

The current feedback experience: A staff members perspective

Imagine this: You are marking essay number 8 out of 15 – and you are really enjoying it. The students have done okay, but you can see exactly what the students need to do to improve their grade. You’re normally not known to spend masses of time on marking, but you spend a full two days, providing elaborate feedback on each essay. The sun is shining, the birds are singing. Life is good.

Two months after, the same cohort submits their second essay of the term. You’re excited to see how the students have progressed from your excellent feedback on their last essays. You open Turnitin, only to find that the average quality is the same as last. Did they even open the feedback from last time?

“Feedback remembered but never used, is not feedback”

Orsmond, Merry & Reiling (2005)

Our current issue: Feedback as a linear journey

This is not an uncommon experience. Undergraduate students are conditioned throughout their educational journey to perceive the assessment-process as an assembly-line: they submit an assessment; it gets assessed; the cycle repeats (Suto and Oates, 2021). In this ‘assessment production line’, the student voice is disregarded in feedback, and thus the students arrive at university as “professional” passive learners (MacLaren and Farrington, 2023, and references therein). Furthermore, written-only feedback has been suggested to limit assessment grade improvement, compared to interactive (auditory or face-to-face) feedback (Mackinney et al., 2021). Is the “traditional” approach to feedback then doomed to fail?

Our proposed solution: Introducing the Action Feedback Protocol

To address this issue, we have sought to learn from the successes of other institutions. Heriot-Watt has recently – and successfully – turned their approach to assessment feedback around from unidirectional to a continuous conversation between the assessor and the assessed. By enrolling the Action Feedback Protocol (AFP), designed by Maclaren and Farrington (2023), the University is aiming to create feedback literate learners. The results were overwhelmingly positive, with an 95% of undergraduate students graduating with a Management degree saying that the felt the feedback they received was helpful for their academic development (MacLaren and Farrington, 2023).

The AFP is designed to be easy to implement, and is flexible to existing rubrics and learning outcomes. It is centred on three main pillars:

1) Tune the ear

To create a consensual conversation about feedback, the student must first be well equipped to have it in the first place. Therefore, the first step of the AFP is to tune the students’ ear to receiving feedback. Resources have therefore been developed to equip the students with tools on how to anticipate, make sense, and take action on their feedback, which draw on resourced designed by AdvanceHE. This step acknowledges the fact that receiving marks and feedback can be an emotional experience for many students.

“There is a common absence of proactive recipience among learners, fuelled by an under-provision of training in the role of feedback in the learning process”

The AFP Team (2025)

2) Simplify the message

Secondly, we need to disentangle what we (the markers) think constitutes good feedback, and what the students think constitutes good feedback. Feedback in this instance should be informative, effective, and actionable. The AFP thus uses the ‘three comments approach’, in which three simple comments are given in response to a piece of assessed work, in the following order:

- Motivational: What was done well, and should be reinforced?

- Informational: What was/were the main area(s)of weakness?

- Feed-forward: What should the student(s) work on in order to improve in the future?

Whereas the motivational and informational comments are specifically related to the assessment, the feed-forward comment points beyond the scope of the assessment, either towards other summative assessments in a course, other courses in their programme, or broader academic practice in general.

3) Encourage Action

Finally, what makes the AFP stand out from the traditional feedback sandwich is the encouragement to take action. For each feedback comment the student has been given, they are encouraged to write an action point, that they will complete for the next assessment.

What is not intuitive here is that the student has to create an action for their motivational comment. However, we believe that is the most powerful part of the AFP. This encourages the student to focus on what they did well, and shifts the focus from feedback being about what they should have done better, to a more holistic image of their current performance and their path to improvement.

The test courses: ‘GeoSciences Outreach and Engagement’ and ‘Research Training for Geophysics’

We trialed the AFP approach to assessment feedback in two courses: GeoSciences Outreach and Engagement (GO&E) and Research Training for Geophysics. Both courses are full-year courses for Honours students.

GO&E is a final year, level 10 course, which is open to all undergraduates from all degree streams. Traditionally, students from all areas of GeoSciences and Physics take this course, but students from Psychology and Archaeology have also been enrolled in the past. In this course, each student is given at least two supervisors – one member of academic staff, and one postgraduate tutor – and are encouraged to meet with them regularly.

As outlined in a different Teaching Matters blog post, this course is very different from other courses in the School of GeoSciences. The evaluation primarily focused on authentic assessment and student engagement, and was therefore very appropriate to trial an approach to assessment feedback that empowers the student voice.

Research Training for Geophysics (RTG), on the other hand, is a third year, level 9 course, required in the Geophysics degree, as well as its various spin-offs (geophysics students are able to specialise in pure geophysics, geophysics and geology, or geophysics and meteorology, all with the option of a master’s year, or a year in professional placement). This course is more traditional in its assessment, as the students are assessed on a written literature review, and the individual written and academic performance in a specialised group research project.

How did the AFP work in these very different courses?

In both courses, we changed the format of the provided feedback to align with the “simplify the message” approach. However, as these courses are very different, the way we fitted the AFP into each course was slightly different.

In GO&E, there are six assessment deadlines spread throughout the course. The first assessment was formative, and in that, we encouraged the supervisors to provide the feedback verbally. After each assessment, the supervisory team was asked to encourage and guide the students to make their action points, in a mix between the “tune the ear” and “encourage action” steps in the AFP, and were revisited individually for each student, thus making it a continuous process.

In RTG, there are two major assessments, both written: the literature review, and the group report presentation. The literature review, due in the final part of semester 1, was assessed as usual, according to the four marking criteria: content; communication; presentation; and referencing. Whereas in GOE, the students received the three comments for each assessment, the student in RTG received three comments for each marking criteria, as marked by the course organiser, Dr. Hugh Pumphrey, to whom we are very grateful for incorporating the AFP into his course.

After receiving both individual and class-wide feedback, we ran a session on “Making the Most out of Your Feedback”, guiding the students on how to utilise their feedback through a set of reflective exercises. This gave them time to write action points from their literature review to use in their group project reports.

So how did it go?

In general, the AFP was very well received in both courses. In GOE, Kay noted two distinct benefits to embracing this format of feedback:

“There were two main advantages to this approach. Firstly, the staff were encouraging reflection on well-handled skills, not solely skills needing developed and this promoted a balanced and inclusive approach to upskilling students. Secondly, the student feedback became much more consistent between staff and between assessment items.”

Given the nature of assessment and supervision in GOE, it also felt very natural to make the assessment feedback process more verbal and conversational, and empower the students to create actions points based both on their strengths and weaknesses.

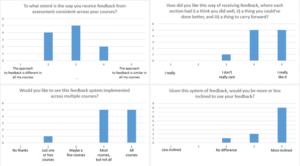

In RTG, as the AFP was rolled out in the more “traditional” sense, with dedicated class-time to train the students to “Tune the Ear”, there was an opportunity to include the students in the decision on using the AFP, and noting their opinions on it. After running the session on “Making the most of your Feedback”, we polled the students on how they perceive feedback currently in their degree, and if they preferred this new approach. 90% of the cohort welcomed using the AFP in most to all of their courses, and a similar proportion felt more inclined to use their feedback if presented in this way.

Where do we go from here?

It was strikingly clear for us that implementing a system like the AFP would benefit nearly all courses. It is easy to incorporate into pre-existing marking rubrics and can streamline the marking processes. Most importantly, it empowers the Student Voice, turning the feedback experience around from unidirectional to communicative.

“Only improvement would be more! If you’d be able to run a session earlier in the year OR in an earlier year”

3rd year Geophysics+ student, enrolled in RTG

As suggested by one student in RTG, this could have even more impact if the undergraduates were trained in this approach to feedback from day one. If all major courses in a degree stream adopted the “Simplify the Message” approach as recommended in the AFP, one could run cohort events on “Tuning the Ear” and “Encouraging Action”. This could both empower the Student Voice in the assessment cycle, moving away from the assessment production line as inducted in schools, and standardise the student experience across multiple courses. We therefore encourage all courses, particularly large, cohort-wide, pre-honours courses to adopt this approach to feedback.

Link to AFP material

Website: https://sites.google.com/view/theactionfeedbackprotocol/

Engage Network: Engaging students with assessment and feedback: a case study in 3D chess from Heriot Watt University – An ENGAGE session with Andrew MacLaren, who developed AFP.

Acknowledgements: Frederik would like to reiterate his gratitude to Dr. Hugh Pumphrey for marking the RTG literature reviews with the AFP approach, and for allowing him to run the “Making the Most of your Feedback” session. We would also like to extend our thanks to Prof. Dan Swanston for the encouragement in writing this blog, and submitting it to Teaching Matters.

References

Mackinney, R., Kelly, J., & Pulling, C. (2021). The effect of feedback type on academic performance. Practice and Evidence of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Vol. 15, No. 1, December 2021, pp. 78-93 https://www.pestlhe.org/index.php/pestlhe/article/view/231

MacLaren, A. & Farrington, T. (2023). The Action Feedback Protocol. In AFP Resources Repository [Accessed 15/04/2025]. Available from: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/kg95yl64751s5t0e8sh2c/ABQ80zbD3aVgk2SNLVIm5yo?dl=0&e=1&preview=AFP+Briefing+Doc_231101.docx&rlkey=0vz08k4qqvdt91rek2t2iae89

MacLaren, A. & Voigt, A. (2024). The Action Feedback Protocol: A journey of innovation and partnership. In the Annual National Teaching Fellows Symposium. [Accessed 15/04/2025]. Available from: https://ntf-association.com/the-action-feedback-protocol-a-journey-of-innovation-and-partnership/

Orsmond, P., Merry, S., & Reiling, K. (2005). Biology students’ utilization of tutors’ formative feedback: a qualitative interview study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930500099177

Suto, I., & Oates, T. (2021). High-stakes testing after basic secondary education: How and why is it done in high-performing education systems? In Cambridge Assessment Research Report [online]. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Assessment [viewed 14 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/Images/610965-high-stakes-testing-after-basic-secondary-education-how-and-why-is-it-done-in-high-performing-education-systems-.pdf

Frederik Dahl Madsen

Frederik Dahl Madsen

Frederik is a PhD student in the School of GeoSciences, and is the school’s tutor and demonstrator and representative. In his PhD, he researches the Earth’s core by investigating how sudden changes in the Earth’s magnetic field – so-called geomagnetic jerks – affect the length of a day. Alongside his research, he spends a lot of time improving his teaching practices within the school, and is heavily involved in the school’s outreach and widening participation programmes.

Kay Douglas

Kay Douglas

Kay Douglas, FHEA, is a Widening Participation and Outreach Co-ordinator, Course Organiser on the Geosciences Outreach Level 10, and teaches data skills on the SCQF Level 7 accredited LEAPS Transitions Course.