In this post, students, Helen Miller and Kris Mihova, along with staff members, Elise Darmon and Heather McQueen, share their experiences of designing groups for group work based on students’ shared interest at the start of the course. Elise and Heather teach on ‘Biology 1B: Life’ in the School of Biological Sciences, and Helen and Kris were students on the course. This post belongs to the Group Work series.

A wealth of research supports the idea that co-operative learning (by group work) has positive effects on academic success, academic relationships, psychological adjustment to higher education and social skill development (Tanner et al., 2003, reviewed in Johnson et al., 1998). Literature on group establishment suggests that while self-selection often leads to cultural clustering, feeling comfortable within a group is a major predictor of success (Theobald et al., 2017). Thus, to balance the social and academic spheres in group work within a first-year biological sciences course, Biology 1B: Life Course, we (Heather and Elise) as course organisers adapted the t-shirt exercise of Glassey (2018) to guide group formation by cognitive connection (shared interest) at the start of the course. Using a teaching space with a group of pods – computer-equipped group desks in a teaching studio (see Figure 1) – we designed the activity as follows:

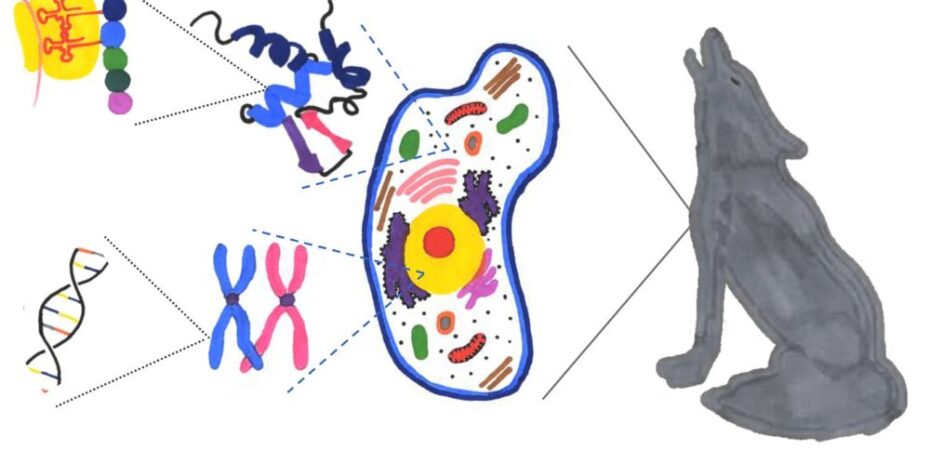

- Hand-drawn cartoon posters, representing different aspects of biology, were mounted at each pod within a teaching studio (see Figure 2).

- Students were instructed to choose a picture of interest and discuss it in groups of four to six with optional discussion prompts provided.

- After five minutes, students were instructed to choose a different pod/picture, travelling independently to maximise the number of people met.

- After five rotations, students were told to return to the pod/picture where they had the best conversations.

- These groups were fixed for all workshops throughout the semester, where students worked collaboratively on skill-building and assessed group tasks with significant agency.

Initial impressions

We all recalled feelings of nervous excitement on the day of the activity, with teaching staff pleased that most students were willing to “play the game” and engage with others early on. As students, we (Helen and Kris) noted that rotations felt a bit fast for meaningful conversations, especially considering the initial first-day jitters. Conversations often took a few minutes to warm up and the text prompts were sometimes disregarded in favour of more casual conversations, which was fine by staff. Teaching staff had some difficulty breaking up conversations when time ran out, indicating student engagement in the activity.

Student experiences – Helen and Kris

As first year students, we participated in this activity in the 2023 session. We both recalled feelings of relief that group allocation was not determined by self-selection, as we feared exclusion due to our sense of cultural isolation from other students on the course. However, neither of us was placed in our first-choice group. My picture of choice (Kris) had no available seats, so I chose the closest available group, which consisted of individuals I spoke to during rotations. I (Helen) initially joined my first-choice pod but requested to join a new group on the first day due to conflict with another student. This was permitted as work had not yet begun. My new group consisted of mostly unfamiliar people at a picture which was of moderate interest to me.

Despite this, we both recalled positive co-operative learning experiences during the course. We found that the shared-interest approach to group allocation resulted in a more cohesive group dynamic than random allocation. In other courses with random or semi-random allocation, we noticed that students often displayed varying degrees of interest in the course topic and therefore had variable expectations of effort and collaboration during co-operative learning. For example, a randomly allocated group assigned to a project on microbiology might have some students who are uninterested in the topic, which may result in frustration and miscommunication among team members.

Staff experiences – Elise and Heather

Overall, we noted fewer interpersonal conflicts in shared-interest groups compared to our prior experiences of random allocation. While the overall success of the shared-interest approach varied from group to group, we observed that most collaborated well and produced high-quality work. Specifically, the shared interest of some groups was central to the tasks they completed (e.g., a group with a shared interest in fish focused their projects on fish). This approach also allowed students to form deeper, personal connections with each other as the course progressed. For example, members of a group interested in fungi would send each other pictures of mushrooms they encountered outside of workshop sessions.

Helen’s experience turns out to be an exception but highlights the gnarly question of what should be done when students request to change groups. If there is a perception that a student is difficult to get on with, we cannot switch everybody out. Instead, we try to apply guidance, support and sensitivity. Kris’ experience could be more easily remedied by not initially limiting final group size but splitting large groups after the choice of pod.

Students felt a deeper sense of belonging

Small weekly focus groups of students were held throughout the course. Interpretative analysis of this qualitative data suggested that like-minded group formation was generally well received and most students preferred this method to random allocation (McQueen, 2024).

“…it felt very natural just speaking with everyone, but then with [other course] it’s taking quite a bit of time … Like I still get on with my [other course] workshop group, but with my [shared-interest] workshop group it’s… so easy in comparison.”

Students noted that the initial conversations facilitated positive communication in workshops throughout the course, and the establishment of a shared interest provided direction on open-ended projects. Altogether, this method of group allocation resulted in groups that communicated well, produced good work and students that felt included (McQueen, 2024).

“I met my best friends during the… workshops. So… I definitely think that that part of the course did help.”

References

Glassey J. (2018). Case Study 20: The T-shirt exercise: developing rapid integration and social cohesion among first-year students. In; Matheson, R., Tangney, S., & Sutcliffe, M. (Eds.). Transition In, Through and Out of Higher Education: International Case Studies and Best Practice (1st ed.). Routledge. pp149-151. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315545332

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T. and Smith, K.A. (1998) Cooperative learning returns to college What evidence is there that it works?, Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 30(4), pp. 26-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091389809602629

McQueen, H. A. (2024). Groupwork can level out educational differences during the transition to university -but class division can confound group cohesion. Association for National Teaching Fellows blog. https://ntf-association.com/groupwork-can-level-out-educational-differences-during-the-transition-to-university-but-class-division-can-confound-group-cohesion/

Tanner, K., Chatman, L.S. and Allen, D. (2003). Approaches to Cell Biology Teaching: Cooperative Learning in the Science Classroom—Beyond Students Working in Groups. Cell Biology Education, 2(1), pp.1–5. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.03-03-0010

Theobald, E.J., Eddy, S.L., Grunspan, D.Z., Wiggins, B.L. and Crowe, A.J. (2017). Student perception of group dynamics predicts individual performance: Comfort and equity matter. PLOS ONE, 12(7), p.e0181336. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181336

Helen Miller

Helen Miller

Helen Miller is a third-year undergraduate student working toward a BSc Immunology Honours in the School of Biological Sciences. She is an international student from the United States.

Kris Mihova

Kris Mihova

Kris Mihova is a third-year undergraduate student studying Biological Sciences (Molecular Genetics) BSc. He immigrated to the UK from Bulgaria with his family when he was seven.

Elise Darmon

Elise Darmon

Elise Darmon is a Lecturer in Molecular Bioscience Education. She is the deputy course organiser and developer of the Biology 1: Life course discussed in the blog post. Elise’s interest is in developing students’ active participation and communication, as well as their confidence and their awareness of the Sustainable Development Goals. She is FHEA.

Heather McQueen

Heather McQueen

Heather McQueen is Professor of Biology Education within the School of Biological Sciences. Her current academic interests lie in active learning techniques, student engagement in large classes and inclusive education, but she is also passionate about canine learning. She is the course organiser and lead developer of the new first year biology course Life 1, and is SFHEA and a National Teaching Fellow.