In this post, Louise Gorse presents the July 2025 Teaching Matters’ reflective round-up: Five issues raised by the ‘Critical insights into contemporary issues in Higher Education‘ series (August and September 2024). Louise is a University of Edinburgh student alumna and current staff member in the Student Support team at the School of Divinity. The Collegiate Commentary is provided by Dr Tom Cunningham, Senior Lecturer in Academic Development at Glasgow Caledonian University.

As outlined in this series introductory post, the issues facing the academic world are in tension with the positive endeavours taking place. By outlining and acknowledging the five issues raised by the ‘Critical insights into contemporary issues in Higher Education‘ series, and engaging in constructive dialogue and debate, the articles create space for a hopeful future.

Issue 1: Mental Health and Wellbeing

The crisis of mental and emotional wellbeing is highlighted by many contributing writers. As Wellbeing Adviser, Tessa Warinner, tells us, the phenomenon of burnout is affecting both students and staff. She refers to the YouGov study, which showed that one in five workers took time off work for burnout symptoms within the year of the survey. Unfortunately, Tessa has observed that students are suffering the same thing:

“In my experience, I have found that students frequently report burnout symptoms while completing their degree. Going to lectures, working on assessments, and attending exams can involve as much energy as someone working a full-time job.”

Tessa helpfully lists the signs and symptoms of burnout, along with advice and steps to take if you feel this may be affecting you.

Vice President Welfare, Indigo Williams, directly addresses the complexity of student mental health. She notes the pressures students face at university, whether it be academic, financial, social, cultural or marginalisation, and suggests we need to recognise these in order to properly support students. Destigmatising and opening conversation around mental health is a way we can all help, and Indigo proposes this dialogue will open doors to solutions such as early intervention and preventative measures:

“Tackling the student mental health crisis requires a collective effort from both staff and students. By taking on the responsibility of understanding and recognising when members of our community are struggling, and by implementing the steps outlined above, we can make a meaningful impact.”

The call for acknowledgement and open dialogue is shared by Dr Avita Rath, who explores the effects of emotional labour on those working in academia:

“This unseen, rarely acknowledged labour is a storm brewing beneath the surface of our work, threatening to drown us in a sea of burnout and exhaustion.”

In order to reduce this burnout, and potential mental and physical health effects, Avita calls for change in the way we prioritise faculty emotional wellbeing to create a future where people can bring their authentic selves to work.

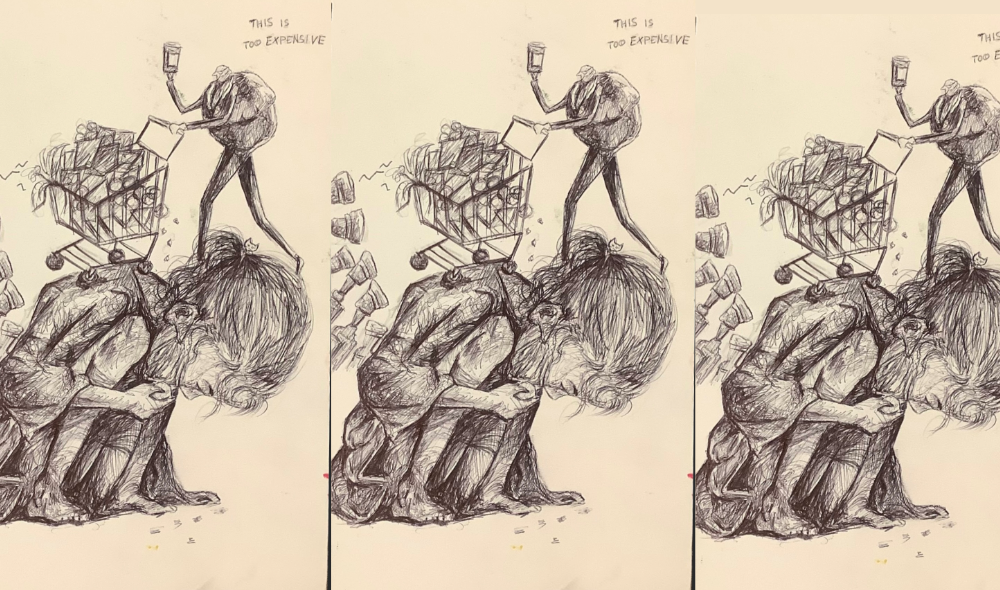

Issue 2: Financial stress and the cost-of-living crisis

The Cost-of-Living crisis is significantly affecting student experience and participation. Dora Herndon and Ruth Elliott explore the ways in which the financial pressures facing students affect the accessibility of Higher Education. They also note the hidden costs of financial hardship, such as increased levels of anxiety, academic performance and ability to engage with teaching. However, by treating students holistically, nurturing their personal wellbeing as well as academic success, they explore ways in which the burden could be eased.

Dr Neil Speirs also highlights the impact of the Cost-of-Living crisis on students, whilst noting that this issue has been prevalent for many years amongst working-class students. He rejects individualism and calls for a community-based response based on Freire’s pedagogy of love and hope. He is optimistic this will create:

“A renewed way of life on campus that delights in the privilege of trust, acceptance and love. And a renewed way of life that is compassionately aware and engaged with the reality of life for all of our students.”

Issue 3: Data-driven education

Another key issue came to light for Dr Charlotte Desvages and Dr Itamar Kastner during the Marking and Assessment Boycott of 2023. Their reflections show an overbearing presence of administrative requirements in regulatory practices, leaving pedagogical goals to fall to the side-lines. They suggest the emphasis of numerical marks should instead make way for a system with pedagogically-informed course and programme design, delivering marks dissociated from feedback:

“Institutional requirements for an aggregated numerical grade can place an inherent barrier for educators seeking alternative feedback and assessment methods which could be more beneficial for learning, and which could in fact contribute to maintaining robust academic standards.”

Dr Vassilis Galanos also draws attention to the presence of metrics across the academic experience, whether it be grading for students or the Research Excellence Framework for staff. He suggests,

“This simplification often strangles creativity and critical thinking. For the imaginative and divergent thinkers, it’s like being shoved into a production line where only uniformity gets rewarded.”

Vassilis’s three-part blog critiques the metrics of academia with reference to the works of Karl Marx. He fears the dangers of metrics being omnipresent, from attendance monitoring to numeric evaluation, suggesting this creates an academic world which often means “playing it safe, avoiding the unconventional or interdisciplinary work that might not score high on the metrics scale”.

Issue 4: Evolving landscape of Generative AI

A key concern touched on in many of the pieces is the evolving landscape of assessment under developing technologies such as Generative AI. In his two-part post, Dr Matjaz Vidmar discusses the impact of ChatGPT on the take-home essay. He notes that if assessment structure is based on problem-solving by working through an abstract example as in traditional learning environments, GenAI poses a threat in student engagement. However, he suggests (and practices in Part Two) an assessment in the form of critical personal reflection on experiential learning and group work:

“For this, design assessment briefs can be designed that are harder for generative chat-bots to respond to effectively. In particular, if grounding the assessment in personal experiences of the operationalisation of theory in practice based on a specific in-course (group) exercise, it is so far impossible for the critical thinking in framing and editing the narrative to be done by generative writing tools.”

He argues that with the development of tools like ChatGPT, the temptation could be to revert to outdated assessment practices, but by drawing on experiential learning we follow leading pedagogical frameworks whilst avoiding the threat of generative writing tools.

Dr Vassilis Galanos also touches on GenAI, preferring instead to call it ‘Degenerative AI’. In the third part of his piece, he argues that the passive acceptance of metrics-oriented culture actually encourages and normalises high adoption of GenAI machinery. Rather than a time-saving tool, Vassilis suggests:

“What Generative AI’s time-efficient output may do, is increase the amount of produced content, but without an unchanged time-table (the contracted hours, or the time prior to entering the job market).”

This, according to Vassilis, could have negative effects on the academic journey, changing it into a rush to meet target numbers.

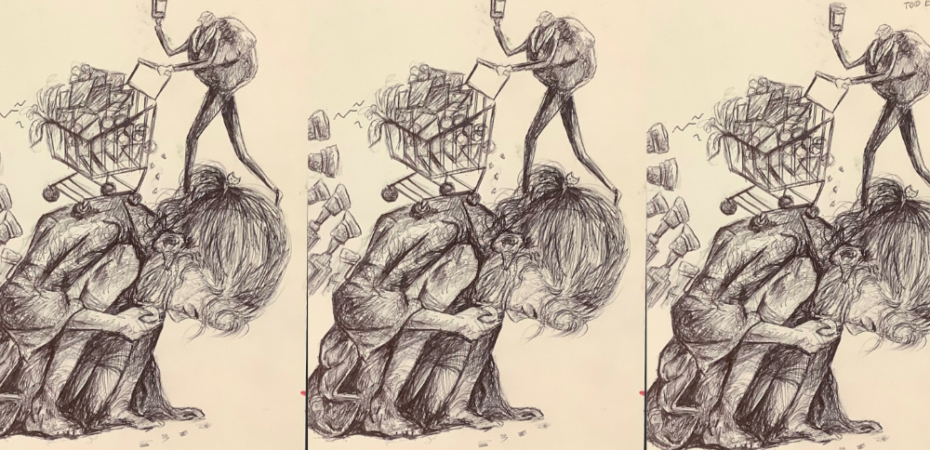

Issue 5: Commodification of academia

Finally, the marketisation and commodification of academia is a common theme across many of the articles. Dr Avita Rath highlights the wellbeing dangers of the transformation of universities into ‘service institutions’, with academics as providers, and students as stakeholders. By acknowledging the commodification of emotional labour in academia, she suggests that:

“Emotional labour is not just a personal challenge but a systemic problem within academia that affects our wellbeing and our ability to thrive”

Similarly, Dora Herndon and Ruth Elliott push for a move away from students as ‘consumers of education’ towards treating them as holistic individuals. It is not only mental wellbeing that is affected by this, using a Marxist framework, Dr Vassilis Galanos likens the process of metrics-oriented culture to the commodification trends in industrial capitalism:

“This relationship turns human intellect into marketable products, since the relationship is mutually parasitical: as much as the industry wishes to present an outwardly-facing, scientifically and moral high-ground with the approval of the academy, while the latter wishes to benefit by collaborations with the industry that increase revenue, prestige, and can be presented as societal impact.”

Conclusion

In summary, the articles in this series approach a wide variety of issues facing Higher Education today. Whilst the topics are critical and challenging, the writers explore ways in which we can create a hopeful future. Through acknowledging the issues, engaging in debate, fostering wellbeing, and working collectively as a community of staff and students, we can make a meaningful impact.

Louise Gorse

Louise Gorse

Louise Gorse is a University of Edinburgh student alumna (2017-2021) and has been part of the University staff since February 2024, serving in the Student Support team at the School of Divinity. She is set to embark on a PhD at Lancaster University in October 2025.

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/louise-gorse-a93456204