I hadn’t planned to focus my first published PhD article on our ‘not knowing’ about intergenerational suicide. I have analysis to share and haunted stories to tell. However, in my work as a PhD researcher (at the University of Edinburgh) and as a psychotherapist, I was encountering surprise from other therapists and suicide researchers: What, suicide runs in families? Our ‘not knowing’ puzzled me. And so, I realised I needed to start with an article that examined what’s happening in our ‘not knowing’. I’m excited to see it published, flying out into the world.

Examining our ‘not knowing’

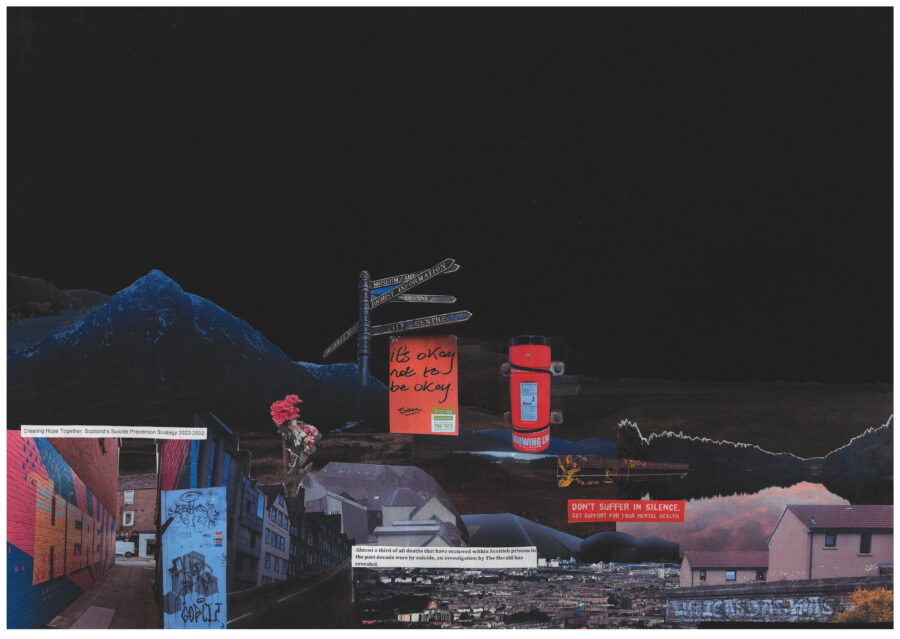

I consider the ‘problem’ of intergenerational suicide to be embedded in sociocultural contexts. Contexts that shut down our knowing and enable intergenerational suicide to slip into silence and continue. What are the sociocultural complexities? In the article, I think with Gabriele Schwab’s take on intergenerational trauma theory. It’s a theory informed by psychoanalytic ideas about the cultural unconscious. I think it offers a useful lens through which to consider intergenerational suicide in families. I enjoy writing with Schwab’s theorising of intergenerational trauma as a language for thinking with the unconscious happenings in the story of (for illustrative purposes) one of my collaborators, Isabella.

Opening up space to think about and know intergenerational suicide differently.

The elephant in the room

As I move through the article, I find myself playfully writing-with-an-elephant-as-inquiry. An elephant called Nelly. She represents intergenerational suicide and the absent presences in the stories of my collaborators. In writing with her, I’m calling on a particular cultural phrase familiar within my British context – the ‘elephant in the room’. It means the presence of something not being spoken about, something invisible. In this instance, it’s the people who have died by suicide; it’s suicide running in families.

A social injustice

I am passionate about this. About examining what’s happening in our ‘not knowing’. This critical examination of what’s happening in our ‘not knowing’ offers opportunity to challenge the status quo of silence, shame and stigma. As opposed to unprocessed trauma remaining hidden within the unconscious. And hidden behind the closed doors of families and therapists’ consulting rooms. Until the next suicide happens.

Reading the article and beyond

And so, here it is, the full article: Stewart, K. R. 2024. What, suicide runs in families? Writing-as-inquiry to examine our ‘not knowing’ about intergenerational suicide. Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/15327086241254813

Whilst I leave you to read the article, Nelly and I have analysis to do, ghosts to hunt and stories to tell. We’ll be back soon.