In this post we continue with a discussion of some of the ethical challenges we are encountering as part of the Suicide Cultures project. Here we will focus specifically on the ethical challenges of working with the Fatal Accident and Sudden Deaths Inquiries (FAIs) of people who have died by suicide in prison. This post is intended as an explicit and transparent reflection on the complexities of issues of anonymization and an ongoing thinking project about issues of care, privacy and critiques of institutional framings of suicide. The reflections we present here have been born out of many discussions within the Suicide Cultures research team, as well as consultation with Sarah Armstrong, Linda Allan and Betsy Barkas, who are also working with FAIs.

As part of the Suicide Cultures project we are conducting an analysis of all the FAIs of deaths in prison due to suicide in Scotland from 2016 until the present. Prisons have been identified as having high rates of suicide (Tomczak, 2018; Zhong et al., 2021). Scottish prisons record higher rates than those in England and Wales, although there are a number of issues which make comparisons problematic (Armstrong & McGhee, 2019). Given that prisons are significant sites of suicide, it is important to explore how suicide is understood and responded to within these contexts. Our analysis focuses on how suicide is constructed within FAIs and the implications of these constructions for understanding the role of the prison environment in deaths by suicide.

When we say ‘how suicide is constructed’, we mean that the ways in which suicide is talked about and portrayed creates particular social ‘truths’ about suicide. These include ‘truths’ about what causes suicide and how it should be responded to. These ‘truths’ come to be taken for granted and regarded as the only explanation for suicide. For example, one of the dominant ways in which suicide is often constructed in research, as well as public policy, is as an individual mental health problem (see Marsh, 2020). This is done through explaining suicide as being caused by mental illness such as depression and proposing that the best way to prevent suicide is through individual therapeutic and pharmacological interventions. These constructions tend to focus solely on the ‘suicidal’ individual, neglecting the broader context in which the individual lives. In contrast, research which focuses on the social contexts in which people live highlights “the heart-rendering suffering, daily indignities, and desolation many people struggle with” (Reynolds, 2016, p.169), including poverty, homophobia, racism and other forms of social exclusion and violence (White, 2017). This kind of work constructs suicide as an issue of social justice rather than an individual mental health issue and proposes that suicide can only be ‘prevented’ by making lives more liveable for all people. It is important to note that these social constructions of suicide are not static and that they change and shift over time[1]. In our analysis we are interested in the kinds of truths about suicide that are presented in the FAIs.

An FAI is an inquiry, conducted by a sheriff, the purpose of which is to “(a) establish the circumstances of the death, and (b) consider what steps (if any) might be taken to prevent other deaths in similar circumstances”. An FAI is carried out for certain kinds of deaths, including when the death occurs while a person is in legal custody. As one sheriff noted in their report “The primary purpose of a fatal accident inquiry (‘FAI’) is to give a public airing of the facts surrounding a death or fatal accident. This affords those with a direct interest, such as the family of the deceased, the chance to hear first-hand from witnesses and learn the full circumstances of the death as they are known”.

These reports are publicly available, to facilitate transparency and public accountability, and include full names and many other personal details of the person who has died, and in some instances of their family, partners and friends. In light of the public nature of these reports, the issue of anonymization to protect people’s privacy is complicated. Normally in qualitative research, we pseudonymise participants – changing people’s names, and sometimes key details, in order to protect their privacy. This allows people to participate in a research project without necessarily exposing personal details about themselves. However, as Betsy Barkas noted in our discussion about working with FAIs, people’s anonymity has already been violated by the state in the case of FAIs, making it difficult for researchers to preserve people’s privacy.

As a research team we have found ourselves asking: how we can present a critical analysis of the FAIs, which explores the often-problematic ways in which people who have died by suicide are constructed, while preserving, as far as possible, the dignity of those who have died, as well as their loved ones who have been affected by their deaths?

We feel that a critical analysis, which draws directly on quotes from the FAIs, is important to be able to both highlight and disrupt the decontextualized ways in which prison suicides are understood, as well as the ways in which the systems and environment of the prison are implicated in people’s deaths. We have all been deeply moved, distressed and angered by what we have read in the FAIs and we hope to be able to draw on some of these feelings in our writing, to communicate in more affective ways about the people who have died by suicide in prison. We recognise that each person who has died by suicide is a human being, deserving of dignity and respect, whose life cannot and should not be reduced to the details of their deaths as recounted in the FAI. We aim to make this point clear in our writing about the FAIs, as well as, as far as possible, not to reproduce harmful constructions of those who have died. We hope that through presenting a critical analysis of the institutional frameworks through which suicide is presented, we can challenge dehumanising representations of people who have died by suicide.

We also recognise that our analysis of the FAIs, which includes potentially recognisable information about the person who has died, may be distressing for their loved ones. We have, therefore, decided not to use people’s real names. We will be using pseudonyms for all participants, as well as removing or altering demographic information in order to reduce, as far as possible, identifying information. However, as we have highlighted above, the publicly available nature of the FAIs mean we cannot guarantee that people will not be identifiable.

It was mentioned in our discussion with Linda Allan, Betsy Barkas and Sarah Armstrong that some families may want their loved ones explicitly named, as this may be an important way of honouring them and the conditions under which they died. It is possible that some of the families of the people represented in the FAIs we are analysing may feel similarly. However, after long deliberation we have decided not to reach out to families. The FAI process is, more often than not, very drawn out and so many of the deaths we will be analysing occurred many years ago. We recognise that some families may find it intrusive to be contacted by researchers after so many years and that they may not wish to revisit the death of their loved one in this way. This is in line with our original ethics application, where we proposed that we would not contact the families. After having seen the reviews, it has also become clear that in many instances the families are not named and therefore finding and contacting them would itself be intrusive and something we feel is ethically questionable.

There are no easy ethical answers when it comes to doing research on suicide, which becomes even more complicated when working with publicly available data collected by the state. The institutional environment of the prison removes certain rights from prisoners, while the FAIs construct their lives backwards through their final act of suicide. In our work we want to take care to avoid creating further suffering for the families of those who have died by treating the subjects of FAIs as whole human beings caught within complex institutional, legal, social, and economic forms of oppression. We hope that by more explicitly articulating our own ethical position, we make ourselves more ethically accountable as we continue this difficult work.

References:

Armstrong, S., & McGhee, J. (2019). Mental health and wellbeing of young people in custody: Evidence review. The Scottish Centre for Crime & Justice Research. https://www.sccjr.ac.uk/publication/mental-health-and-wellbeing-of-young-people-in-custody-evidence-review/

Marsh, I. (2020). Suicide and social justice: Discourse, politics and experience. In M. E. Button & I. Marsh (Eds.), Suicide and social justice: New perspectives of the politics of suicide and suicide prevention. Routledge.

Reynolds, V. (2016). Hate kills: A social justice response to “suicide”. In J. White, I. Marsh, M. Kral, &. J. Morris (Eds.), Critical suicidology: Towards creative alternatives. University of British Columbia Press.

Tomczak, P. (2018). Prison suicide: What happens afterward? Bristol, Bristol University Press.

White J. (2017). What can critical suicidology do? Death Studies, 41(8), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2017.1332901

Zhong, S., Senior, M., Yu, R., Perry, A., Hawton, K., Shaw, J., and Fazel, S. (2021). Risk factors for suicide in prisons: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health, 2020(6), e164-74.

[1] For example, in many contexts suicide was historically regarded as a criminal act. In contemporary societies this ‘truth’ has been replaced by the ‘truth’ that suicide is caused by mental illness.

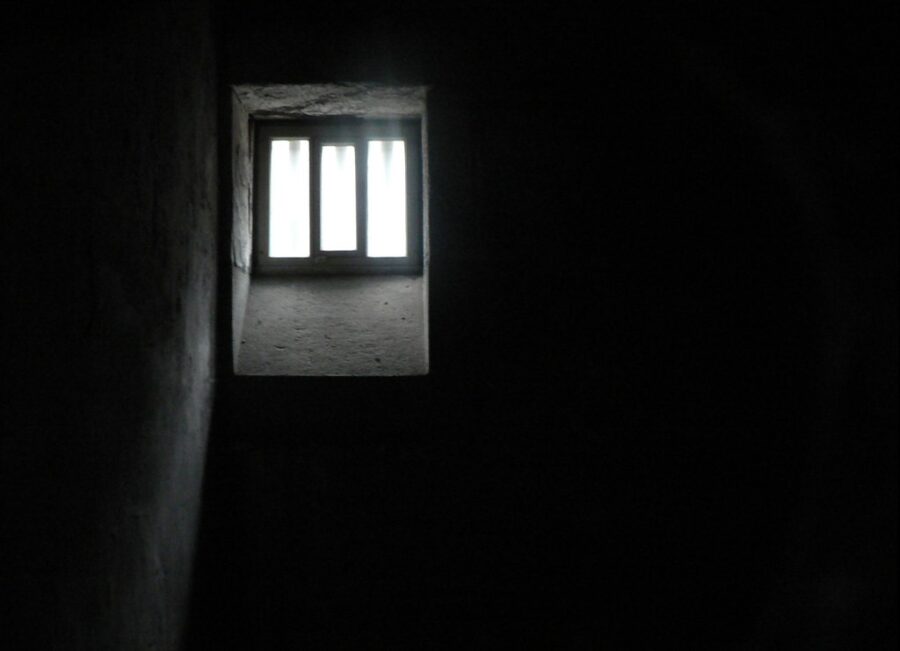

“Prison cell” by decade_null is licensed under CC BY 2.0.