by Joe Anderson

Here at the Suicide Cultures project we have been hard at work all over Scotland gathering data about people’s experiences of suicide. In our interviews, the events we have been attending, and in the notes we’ve been keeping about local areas, we have been privileged to hear profoundly moving stories about people’s struggles and their resilience in the face of huge challenges.

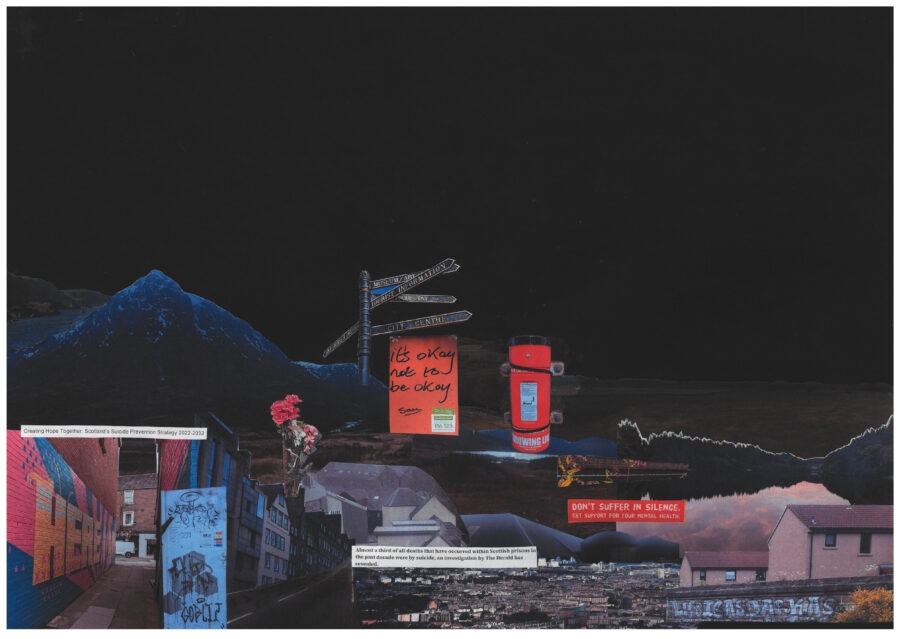

One of our aims with this work is to understand the contexts in which suicides happen. This means thinking beyond dominant ways that the medical field, psychologists, and many researchers construct suicide by thinking of it as a result of mental illness. We want to challenge the idea that contemplating and attempting suicide, as well as the grief that follows bereavement by suicide, is located only in the mind, instead proposing that there are many other dimensions of human life that are implicated in suicidality. This includes how suicide is embedded in the physical, social, emotional, and political geography of the areas we are working in to get a larger image of the complex ways that distress is generated within institutions, discourses, and systems.

Some of the people we have interviewed and spent time with have told us about difficulties with their mental health, while others have explained their suicide attempts as related to their need to escape abusive relationships, the ongoing fear produced by financial insecurity, as well as the negative emotions that accompany not fitting in or social and physical isolation.

Our desire to map and understand contexts that contribute towards suicide has led us to propose the concept of Suicidescapes. In the rest of this blog, we outline why this concept is useful for understanding suicide in Scotland and crucially, how it helps us think differently than work that sees suicide as a problem to be solved only with individual responses like talking therapy and pharmaceutical medication. Excitingly, this new way of thinking has the potential to generate interventions that acknowledge how suicide is bound up with many different scales of human experience, from the individual and familial, to larger communities and cultures.

Why Suicidescapes?

After spending time with literature from the field of Geographies of Death, we came across the concept of ‘Deathscapes’ – an idea that acknowledges that death has both a physical association with particular spaces, like cemeteries and memorials, and a social-emotional life that extends beyond them. For example, death is present for the mother of a child who has died far beyond the physical space of their burial. A photo on a mantelpiece may evoke their presence, an activity that used to be shared may provoke waves of emotion, while the story that people tell of someone’s life and death takes on a larger social meaning when it is shared among a community.

We recognise that suicide is a particular kind of death, often marked by silences and a sense of taboo. As one participant in our research said, when someone dies of old age or from an illness it is tragic, but when someone dies by suicide you have to deal with complex emotions that reflect the uncertain nature of why someone would take their life and whether more could have been done for them. There is also the silence and taboo that often accompanies suicide more generally in our society that can make a loved one feel isolated or misunderstood. This separates these deaths out as particularly challenging for families and communities who have to grapple with the uncertainties left behind. We felt that Deathscapes could be extended to help us understand why suicide seems to carry such fraught moral weight within private and public spheres.

The concept of Suicidescapes allows us to account for the ways that suicide occurs in local areas as it becomes associated with physical landscapes (in other words, where it happens), the emotions of the people involved (how it feels when someone dies by suicide), and the stories that are told and shared among the people or communities affected (how suicide is constructed and explained). By thinking of these three levels as connected yet distinct, real yet imagined, we want to emphasize that knowledge about suicide is never free of the moral judgments that abound in its wake. The way we think about suicide affects how it appears and is responded to.

So, if this concept is supposed to help us understand the contexts in which suicides happen, what does a Suicidescape actually look like?

What is a Suicidescape?

Let’s use a bounded example that we are working with in our project – suicide in the context of prisons. Prison is a unique Suicidescape that elicits suicide at higher rates than in the general population of Scotland. While we could say that suicide in prison occurs because of mental illness or other individual risk factors like drug and alcohol use or specific life trauma, Suicidescapes asks us to look at the ways that the physical, social, administrative, and emotional logics of prison life play a role in creating conditions that invite suicidality.

First of all, prison is designed primarily as a space of punishment, where shame, exclusion, and dehumanisation are enacted on people who have broken or are accused of breaking particular laws of the state. The stigma that accompanies being incarcerated or even having been in prison in the past is clear to see. The social mark of prison can make an individual feel they are different than others. Secondly, even when prisons aim to improve the mental health of their residents, they tend to implement policies that further the punitive logics of incarceration. People who express suicidal thoughts are closely monitored, even woken multiple times throughout the night to ensure they have not attempted suicide. In some cases, prisoners are strip searched for sharp objects, placed in special anti-suicide clothing, and isolated alone in a cell so they can be more closely monitored. It is easy to see why each of these interventions may further compound someone’s suicidal distress.

Suicide is constructed by the prison as an issue of tighter regulation and control, rather than care and compassion, therefore justifying punitive measures. In this example, our concept has illuminated that the way suicide is constructed as a problem within institutions or cultures relates to the larger societal function of that institution. This case study demonstrates how we are conceptualising the spaces we work within across Scotland. Each unique area encompasses a variety of landscapes, institutions, social norms, cultural practices, discourses, and types of population that make up its particular Suicidescape, although it is never fully bounded and is in relationship with larger national and global Suicidescapes.

For more information about how we are representing these spaces have a look at our audio-visual poster in a previous blog post.

How does this help us understand suicide?

This concept is helping us to understand and imagine suicide in new ways. It avoids reducing suicide to individual risk factors, like mental illness, and instead embeds the issue in the wider social and cultural networks, as well as the physical landscapes in which it takes place. At the same time, our work allows each individual we engage with to define their experience using their own words. This is giving us data about the reality of the emotions that accompany experiences with suicide as well as allowing people to speak about suicide in ways that goes beyond the mental illness model.

This approach also helps us to hold tensions and disagreements about suicide without seeing these as necessarily contradictory. When professionals in suicide prevention organisations and the medical profession, service users, and people with experience of suicide disagree it offers us an opportunity to understand where our models of suicide are going wrong. It also allows us to see how frustration and anger about seemingly unrelated factors such as the current cost of living crisis, the inability to access services for drug users, or reductions in funding for public transport links in deprived rural areas might be related to someone’s expressed desire to die. This concept pushes us to see inequality as an active ingredient that produces harm in Scotland and around the world, including increasing suicidality.

Finally, Suicidescapes gives us a practical way to map suicide cultures in our study. By focusing on the physical environments in which suicide happens, its accompanying emotions and social interactions, as well as discourses about suicide we can see how deaths are produced by and become part of the cultures in which they occur.