By Ray Honeysett

Africa has immense diversity of culture, and with this comes a vast and varied knowledge of astronomy. Countries in Northern Africa have a different view of the sky than those in the southern hemisphere, making Africa the continent with the widest-spanning view of the night sky.

Much of the oldest evidence of astronomy can be found in Africa – even the pyramids of Giza are aligned to the cardinal points of a compass, with slits within the Great Pyramid pointing to some of the brightest stars in the sky. Science bloomed in northern Africa up until the 16th century, with many Arabic texts on the topic of astronomy being written and traded there.

Sadly, as European empires expanded, they destroyed much of the traditional African methods of astronomy. Not all is lost though; some cultures, like the Dogon people and the Bushmen still live their lives by the stars. In this article we will look at the history and ongoing research in astronomy across Africa.

Egyptian Astronomy

The oldest surviving observatory is in Egypt, on the Sudanese border. At over 7000 years old, the Nabta Playa stone circle predates Stonehenge by millennia.

The gates of the circle align with the placement of the rising sun at equinox and solstice. This was very important to this civilisation; if they could tell what time of year it was, they could predict their rainfall season, and know when to plant their crops so that they would be most likely to thrive.

Six stones in the centre of the circle have been said to align with the brightest stars in the Neolithic sky, Sirius, Arcturus and Alpha Centauri. These stars were great aids in navigation at the time, exceptionally useful to people trying to move through the Nubian Desert, where the Nabta Playa is situated.

Egyptian contributions to astronomy are not limited to ancient times; the Helwan observatory in Egypt made history in 1909 for being the first observatory to take detailed viewings of Halley’s comet, which it observed for 3 years when it was close to the Earth, far longer than it could be seen with the naked eye. More recently, the Kottamia observatory has been built, known as the “Northern Eye in Africa” for its vast mirrored dome. It has been updated with modern astrophysical technology, making it still relevant today.

Mali Astronomy

“When they used to talk about Galileo, I used to ask myself “What about us? What were we doing?’ … There is evidence to suggest that the subjects taught (in Timbuktu) included astronomy, maths, optics, literature, law, Islam…” – Dr Thebe Medupe, 2006

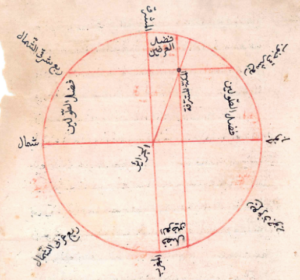

15th century Timbuktu was a haven for scholars, with teachings done in astronomy, optics and maths. Abul Abbas, an eminent astronomer at the time, wrote what he saw as the uses for astronomy.

The first was celestial navigation, an ability that had served Mali well in their building of the Mali empire.

The second was time keeping, knowing what the seasons were and what time of year it was, so that agriculture could be organised in accordance with the expected weather. Abbas created an algorithm to figure out when leap years in the Islamic calendar should occur. In 2008, scientists made his algorithm into a computer program, and were able to show that Abbas was correct.

The third use for astronomy, was what he called “decorating the sky”. Although less scientific, its unsurprising to see that people throughout history have seen the beauty of space as a blessing.

As a devout Muslim, these uses had a special significance to Abbas. By using the stars to time-keep, he could make sure that this prayer and devotion was regular, and by using the stars to navigate, he could face his prayer mat towards Mecca.

Today the tradition of Mali astronomy continues in the lifestyle of the Dogon people. When interviewed by scientists in late 90s, Dogon elders were able to describe in detail the positions and riding times of the Pleiades. Modern star-tracking software has proven their knowledge to be accurate. Knowing things like this is very important to the Dogon; they use it to determine when to expect the rainy seasons.

South African Astronomy

The Bushmen of South Africa use their knowledge of the stars to navigate, and tell the time of year, just as they have done for many centuries passed. To them, the stars have special significance culturally; they have their own constellations with meanings as rich as the ones that originate from Greek mythology. The three stars that make up Orion’s belt in European astronomy are seen as representing three zebras in Bushman tradition.

South African astronomy continues today not only in the continuation of the Bushmen’s way of life, but also in the form of SALT (South African Large Telescope), the largest optical telescope in the southern hemisphere. Recently, its observations have been used to study super-massive spiral galaxies and supernovae.

About this article

This article is part of a series exploring astronomical research from around the world. To find articles about other continents, check the ‘Under the Same Sky‘ tag.

This article was written by Ray Honeysett as part of her student internship role with the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Committee at the School of Physics and Astronomy. This role was part of the Careers Service Employ.ed on Campus scheme.

Ray is currently studying for a MPhys in Astrophysics.

(Raymbetz via Wikipedia Commons)

(Unnamed Algerian tome written in 1575 via Medupe, 2008)

(Lengau via Wikipedia Commons)