To help us refine our final question into a small piece of research, yesterday we held a Q&A with three researchers from the University of Edinburgh who study depression and work with cohort studies: Mark Adams, Alex Kwong and Matthew Iveson

Q&A

Hi all!

Mark: Hi, everyone, I’m a statistical geneticist (meaning I use maths and computers to study genetics). I work on very large scale genetic studies of depression, comparing DNA between people with and without depression using data from countries all across the world. I’m also interested in how depression symptoms might or might not relate to each other.

Depression Detectives member I (DD I): Which cohorts do you work with /have access to for this project?

Mark: We could use UK Biobank, Generation Scotland, and (possibly) ALSPAC (Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children)

DD S: What are the timescales of each of those? (Sorry I know you’ve posted links but I haven’t had as much time to read for this as I’d hoped). The longer the better if we’re looking at recurrence of depressive episodes over lifetime…

Alex: Do you mean the timescales for completing the research or how long the data has been collected for?

DD S: How long the data has been collected for

Mark: In Generation Scotland, our initial measurement was retrospective (asking people to recall past experiences) and they can be initially grouped based on that response. 10 years later we asked the participants again, so it would be possible to look at people who initially did not report an experience of depression, but did have an episode subsequently. UK Biobank is similar, with a 5 year gap to the follow-up. The other way to look at it would be using health records (hospital, GP, and prescribing).

Alex: So in UK biobank we have data collected at multiple waves across ~10/12 years. In that time people would have been asked to think back about how many episodes of depression they had (which can be problematic as you might imagine). In Generation Scotland there is a similar method where people have been followed up over time but have been asked this specifically. There is also the possibility of linking to health records as well which could provide further validation for these self reported measures.

Matthew: Hi all, I’m mid bedtime with my 3 year-old so apologies if I have to duck out. I’m a researcher in the Psychiatry department focussing on using routinely collected health data to examine life-course risk factors and mechanisms underlying depression.

DD S: Sorry! We found with my last project (with parents of small children) that we needed to put the Q&As quite late, or everyone was still doing bedtime. Baby books lie!

9pm is quite impressive for a three year old though.

DD C: I was just feeling proud of myself for extracting myself from my 7 year old’s bedroom in time to be here!

DD M: We managed 8.40pm with ours. Whoop!

DD S: My 7yo is still up, but he’s watching TV…

Alex: Hi everyone, I’m Alex and I’m a mental health researcher like Mark and Matthew. I normally work on data from young people and look to see how depression changes across adolescence and why there are different patterns of depression for some people and not others. I normally look at genetic and environmental factors like childhood trauma, bullying and relationships. But then more complex factors like parental depression which could be a mix of both genetics and the environment.

DD C: How do you even begin to untangle all of that?!

Alex: With great difficulty that’s for sure! We don’t tend to do all of it in the same piece of work. Normally we will have a specific question like how does parental depression impact on their children and try to examine that specifically.

DD C: Sounds like the only possible way! What research methods do you use to investigate these questions?

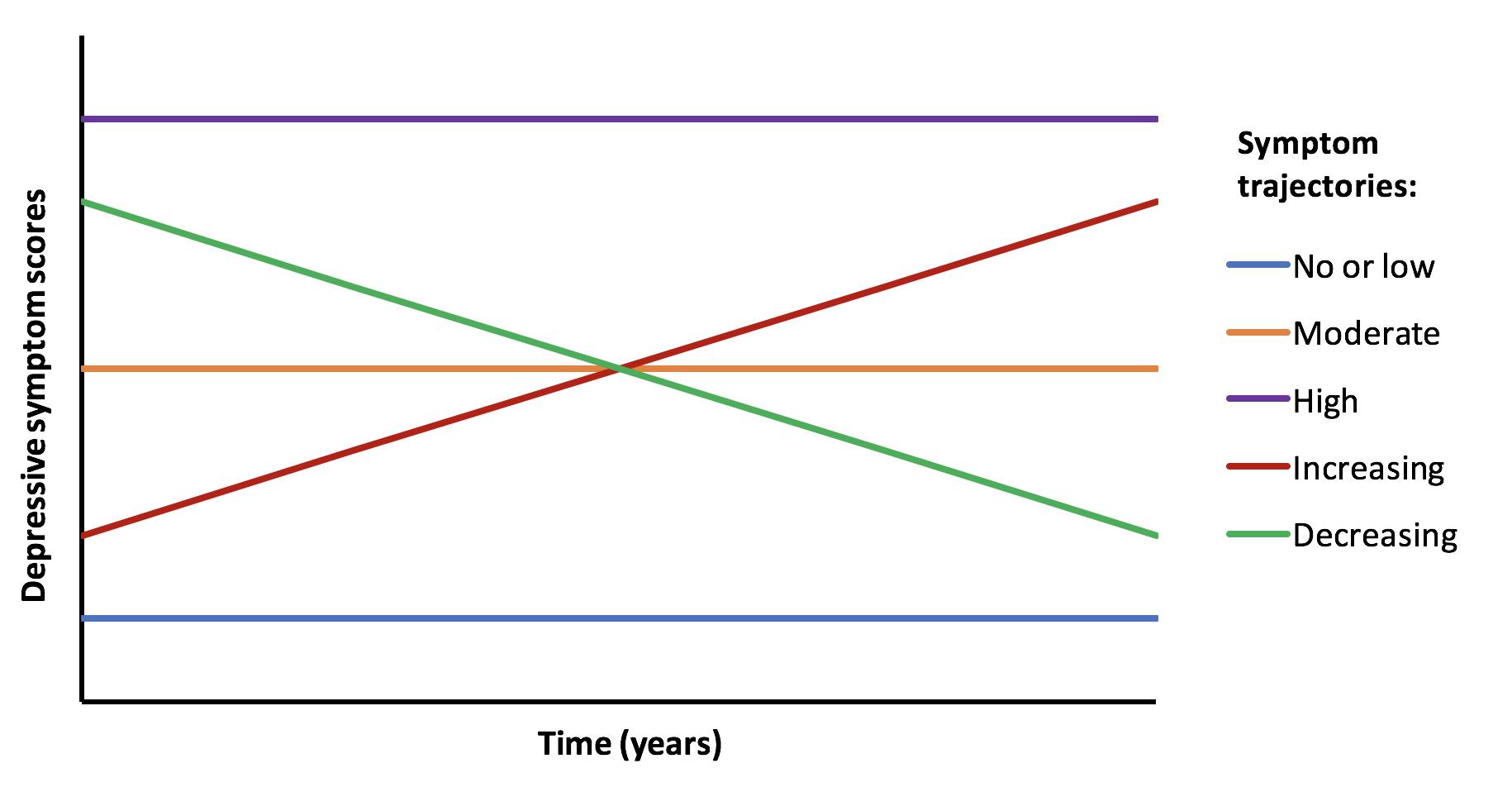

Alex: Excellent question. So there are multiple methods but my preferred method is to look at trajectories of people over time.

So let’s say someone completes several questionnaires about depression over time (maybe every year for 4 or 5 years), we then create a trajectory for that person. If you have 100 people then you have 100 trajectories and you can start to see how people differ and if these are specific characteristics for different groups of people.

So you may have something that looks like this image below.

More info here

DD C: I’d be really interested to see how you ask about depression. I know that my personal experience of depression is very different to the questionnaires I was supposed to use for screening when I worked as a medical doctor.

Alex: So each cohort is different and that is one challenge. But I have used this measure quite often – the short mood and feelings questionnaire. It was mainly aimed at looking at depression in children and adolescents, but can be assessed for older people as well. It’s definitely not perfect but on average those who score higher on this questionnaire are more likely to meet the criteria for depression assessed by a GP

DD C: Thank you for sharing that. It looks pretty standard. I really find it hard to reconcile these questions with my 40 years of experience of being depressed and would be interested to hear if others agree. For me, it went far deeper than that and this sort of questionnaire only scratched the surface. I am also prejudiced against it as I found many patients in elderly care medicine were labelled as being depressed on the basis of a questionnaire like this, whereas the truth was that it was perfectly rational and reasonable for them to feel low and hopeless when they were trapped in a hospital bed for months on end and the appropriate treatment was not to give them SSRIs!

Alex: Yes I can see your point. I think the questionnaires just scratch the surface as you say and there is a lot more detail that could be asked.

DD C: I guess the added detail would negate their use as a quick screening test though. On the other hand, I think there is a difference between the sort of depression which is encompassed by those questions and the sort which is more complex and this is relevant to treatment, given that some depression may be adequately treated by standard GP options, while other forms require years of talking therapy plus whatever else.

Alex: Yes it’s a double edged sword really and as you say there is like an academic version of depression (assessed through these quick fire questionnaires) and then the actual real life depression that people face on a day to day basis.

DD C: My biggest concern with this research question is how to recruit the single episode group. From the survey you did, we’re a bunch of long-haulers! How would we attract people who have had a single episode in the past and interest them in becoming part of our study? And how do we know that it’s only 1 episode and they won’t relapse again in the future?

DD E: Perhaps we need some kind of “survival analysis” for time to next episode?

Matthew: It’s totally possible to run -time-to-event’ studies with multiple events. It gets tricky depending on the variation in number of events, so an alternative is to break down ‘classes’ of trajectories – are those with 1 episode different to those with 2-3 episodes, and different to those with 4-8 episodes, etc.

DD C: That’s an interesting thought. I guess the only way we can know it’s a single episode is to follow them up until death, which isn’t exactly practical! Maybe what we need to look at is the difference between people who dip down occasionally and infrequently but are well between episodes versus those who are chronic?

DD E: Or have another endpoint, like 15 years worth of follow up. This is how things like cancer recurrence are studied. But i appreciate Matthew’s point about the scale/trajectory/frequency of depression mattering too.

DD E: There must a wealth of data in Medical Records at the Royal Ed of one-off receive episodes as well as CDD

Matthew: I think some of the GP and hospital records for Generation Scotland go back to the 1980s, though I can’t guarantee their quality or useability

DD C: Yes, I can see that a lot has changed in psychiatry since the ’80s, so that could be a very messy process to embark upon….

DD I: How do you define single episode? What does it look like in your data?

Mark: Defining a “single episode” is difficult. When does an episode “end”?

DD E: Do the data you study have groups of folks who have single episodes of depression and another with multiple episodes? My hunch would be most patients are in the latter category, but maybe the data can’t say so, or say otherwise.

Mark: We find in our data about an even split between people who only report a single episode and those that report more. It would be interesting to compare health records between the two groups.

DD N: Surprising (to me anyway)! Is that based on self-reporting or GP records?

DD S: I’m sorry, I didn’t see the papers you’d shared below until a few minutes ago. I’m just having a look now. Is chronic depression just being depressed forever (rather than it coming and going)?

Matthew: Chronic is generally having diagnosis-level symptoms for 2 years or more, affecting you for more days in a week than not.

DD I: Part of the question is about single episode vs chronic depression /multiple episodes.

What measures would capture that?

Matthew: It’s always worth thinking about “in an ideal world, how would we measure that”. The best way would be to follow people over time and ask them about symptoms of depression that they’ve recently (rather than having to recall an experience that may have happened years or decades ago). Unfortunately there are no large genetic studies with such short follow up intervals. ALSPAC probably comes the closest, followed by whatever information we can glean from health records in other cohorts.

DD I: Within ALSPAC did they ask both parents?

When the kids got old enough, did they get the depression questionnaires too?

DD I: We have had some discussions in the group about what is not captured by GP records (for various reasons).

You mentioned in the group that ALSPAC asks people to fill in depression questionnaires regularly.

Could these be compared to what is in GP records? Eg suspected depression from questionnaire data vs confirmed by gp

DD C: Are we able to get hold of their depression questionnaire to see what they ask? That could be a good starting point…

DD I: Is the questionnaire online?

DD M: There’s a standard depression questionnaire… GPs also use the depression forms. I think PHQ9 is the one I know

DD C: I’d be interested to know what other people in the group make of the standard GP questions as I found they were a very blunt tool and didn’t encompass my lived experience of depression at all. Maybe I just had a different form of depression to the standard version!

Alex: You could compare self reported depression from a questionnaire to GP records. But there are some things to bear in mind. Firstly, not everyone who has an episode of depression will go to their GP. So you may be missing information there. The opposite could also be true in that someone may go to their GP when they’re depressed, but may not fill in a questionnaire because the survey wasn’t asked at that time.

DD C: Are GPs supposed to carry out the standard questionnaire and put the result in the records or do they just use their clinical judgement? If the latter, then is the diagnostic process powerful enough for it to be included in serious systematic research? It’s been a long time since I bothered going to the GP with a depressive episode, but when I did I was never formally assessed. The first time, the GP took great pains to differentiate between whether I would walk out of the way of an oncoming bus or whether I would step into the path of said bus etc etc, but I have never been asked the standard questions such as I learnt at medical school. My understanding of clinical research (I also used to be a researcher, but that was cellular and molecular so very different) is that you need to standardise the diagnostic process.

DD M: In my experience it varies

Alex: So I think GPs can put scores from a questionnaire on health records. This is actually quite common for those with perinatal depression. That said, my understanding from talking to a lot of GPs is that it’s a bit time consuming to run these questionnaires and it’s better done by primary or secondary specialist care.

DD M: Interesting 🤔 I think PHQ9 is really quick, but maybe not for the first time

DD C: Fair point, but does that mean that GP records are less valuable as a means of research data if the diagnostic process is, how shall I put it, non-standardised!

DD M: Could we not look at prescription data in that case?

It would be skewed slightly by use for other conditions though. And we’d have to be v cautious re amitriptyline as its also used for certain types of pain relief

DD C: Only if we are only investigating depression which has been treated by medication. I stopped taking anti-depressants a long time ago but had several episodes which I managed without drugs and without seeking help from my totally useless GPs.

Matthew: Prescribing data also covers therapies and social prescribing (as long as they were prescribed)

DD C: But only if prescribed by the GP. This assumes that everyone’s treatment is being coordinated by the GP or another NHS professional. We don’t know how many people give up on their GP after years of ineffective treatment and go off and sort themselves out, like I did. I would never want my GP records to be used in serious research because they would give such an incomplete picture.

DD S: One basic question is, as far as the research literature goes, what proportion of people do you think have one single episode, vs have several episodes?

And is there a typical pattern to that? (Like, age of first episode, frequency of episodes, etc)

Matthew: There’s a bit of a problem in terms of how you define an episode, generally. A person with chronic depression could look like they are having one long episode (2years+), and are very different to the typical ‘episode’ of depression in major depressive disorder. If you look at health records (e.g., prescriptions) you can estimate episode numbers and lengths, but it’s only ever an approximation

DD C: In what way do you think we could best define or operationalise the term “episode”?

Matthew: I think taking it literally is best. An episode can be any length (though the DSM criteria is min of 2 weeks), but when that length gets above 2years then we should be calling it chronic

DD S: When you say chronic depression, does this include dysthymia, or is it a chronic version of more severe depression? And do you think these differ qualitatively, or only by degree?

DD M: What’s the difference between major depressive disorder and chronic please?

Matthew: I’ll preface this by saying I’m not a medical professional. My understanding is that major depressive episodes are sufficient depressive symptoms lasting 2weeks+, major depressive disorder is having 2 or more episodes, and chronic depressive disorder is having symptoms for over 2 years. Dysthymic disorder is a little confusing, as it is often lumped in with chronic, but many consider the symptoms to be lesser in dysthymic disorder

Mark: Major depressive disorder includes somatic and cognitive changes as well (extreme changes in sleep, diet or weight, or lack of energy and concentration) whereas chronic depression could occur with only the symptoms of low mood and lack of interest in activities.

DD M: Aha, that’s really interesting. Thanks

DD S: That’s interesting, ‘chronic’ by that definition does sound more like dysthymia. It also raises the question of whether there are qualitative differences in the pathophysiology, between people with the somatic and cognitive changes too, and people with only mood issues – any thoughts on that?

Mark: Yes, the non-mood symptoms all implicate circadian rhythms.

I think somatic and cognitive changes are a bit different because they are more liable to snowball (poor sleep leads to fatigue, which causes concentration problems, etc)

Sarah: Hard to tease out cause and effect as you could argue ways that all 3 types of symptoms affect the others…apparently the cognitive ones often don’t fully remit between episodes, despite mood improvement (to allowing normal fluctuations within ‘healthy/normal’ range) so are they independent to at least some degree?

DD E: I hope this is an appropriate question – Where does Bipolar Depression rank in Long term depression?”

DD L: Bipolar is often considered separately in research studies, so it would depend on the study but often a study on long term depression wouldn’t look at bipolar.

DD N: Something that’s come up in talking about this question is how you measure how many episodes of depression someone has had, since not everyone will go to the doctor every time they have an episode – do you know if there’s any existing data on how those things compare?

DD M: Plus I think relying on self reporting will be unreliable

Alex: Yep self-reporting isn’t very reliable, but it could give more depth than the questionnaires – it can pick up on things the questionnaire designer hasn’t thought of. Plus even knowing that there is a difference between what’s recorded and how people perceive their medical history is in itself interesting (just doesn’t tell you the cause of the discrepancy)

DD S: This is what I am wondering. If ALSPAC is giving people a depression questionnaire once a year, that could pick up episodes of depression that people don’t go to the doctor with (and therefore would be invisible to electronic health records). Has anyone done that analysis? Comparing depression according-to-the-questionnaire to depression-according-to-health-records for the same population, and seeing how they differ?

Alex: Nobody has looked at this yet but this would be an interesting option and something that could be done.

DD S: I wonder what depression questionnaire they use – does it cover the last year, or only how participants are feeling at that moment?

Alex: In ALSPAC, depression is measured using the short mood and feelings questionnaire when assessing depression in young people and then the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in the young people’s parents. Even though it says postnatal, it can still be used when people are not pregnant. These are self reported questionnaires and can be completed quickly. There is diagnosis data from more advanced screening measures as well but these are the most commonly assessed in this cohort.

In Generation Scotland, a different measure called the GHQ28 is used whilst in UK Biobank, the PHQ4 and PHQ9 are used.

DD S: So just at that time then – could miss any depressive symptoms that occur between the yearly questionnaires?

DD N: Do you think it might be possible to extrapolate from that to an idea of the total number, including people who had a depression episode at other times of the year?

Alex: In regards to timing, most questionnaires will only capture the last 2 weeks or the last month. So this poses some problems like what if you catch someone on a bad day? This is an example of measurement error which is a really common problem we have in mental health research

DD M: Catching someone on a bad day would be better than on a good day though?

Alex: I think it extends both ways and both ways are potentially a problem depending on your point of view. Good news for the person if they’re having a long episode of depression and have a good day (hopefully the start of more good days) but bad from a researcher point of view if it’s just a good day in isolation and an anomaly with regards to the data.

But essentially yes, this is a problem sometimes.

DD L: Is there any existing research on predictors of chronic depression or dysthymia? Just found this article – are we thinking of doing something along these lines?

Matthew: There’s also a recent paper from a Brazilian cohort (all middle-aged civil servants, only 2 waves) that shows education and female sex predict persistance

DD S: Well we definitely aren’t going to be able to follow people for 11 years! We’ve got, like, two weeks… But we do have access to the data several cohort studies have been collecting, so we can ask questions of their database…

DD I: With our question as the starting point, what question would you ask the data?

Mark: I’d start by seeing if we can use health data to differentiate people who reported (retrospectively) having single versus recurrent depression to see how closely that data matches what people remember.

Health data is what we call “prospective” because data collection started before the event you want to capture occurs. This will not be totally true because health records only go back in time so far, but there are some statistical methods we might be able to apply to get around that.

Alex: I would agree with Mark. If there is the possibility of using self reported data AND health records, then you can verify if the two are correlated and be more confident in your data.

DD S: I thought we have the (anonymised) records from the cohort studies, but there’d be no way to identify and ask those specific individuals about their perception?

Matthew: I think once we’re happy to use health records to estimate episodes and that it’s reasonably accurate, then a simple question would be something like “what does a life of episodes look like? How are they spread out, when (in life/year) do they occur more frequently?” and also “What risk factors predict more episodes?”

DD S: My concern with looking at the pattern alone, is whether it would add anything novel, although I’d be very interested in the result! But if we look at patterns in combination with risk factors, or treatments, that might be useful? I’m just not sure what’s been done already. That said, being in the UK might be novel (healthcare system different from other countries), also the combination with risk factors / protective factors / treatments that worked or didn’t, might add useful information?

Matthew: I think Mark Adams is talking about comparing the questionnaire responses that the cohorts have already completed (including several waves of depression questionnaires) to the health records we have for them. If someone reports a depressive episode in the last 12 months can we see this in their health records?

DD I: Our question speaks to biological, psychological, behavioural and history eg. trauma.

This is pretty wide.

What do you think might be the key to the difference between single episode and multiple/chronic. (Even just a hunch)

What measures do you have within the cohort studies that might speak to that?

Mark: Based on what we know from family data, my hunch is that single episodes of depression are more situational.

DD L: Yes, I would expect people with higher early life stress to have more chronic depression, with single episodes linked to a stressful experience in adulthood but less early life stress.

DD E: I would like to ask what method of study will the survey take, qualitative or quantitative?

DD L: It depends on what the specific research question is. Pretty much everything the panel talked about tonight would be quantitative because it would be using large amounts of numerical data.

DD S: From the Generation Scotland paper you linked to, “We found that the heritability of recurrent Major Depressive Disorder illness course was significantly greater than the heritability of single MDD illness course.” Do you think that means that a single episode of depression is almost a thing that could happen to anyone if the right (wrong!) circumstances come together. Whereas recurrent depression is more to do with people having a genetic vulnerability to it?

Mark: Yes, that’s a good conclusion. Also about 75% of the genetic risk is shared between single and recurrent, meaning that the genetic vulnerability is very similar.

Alex: I remember reading a paper which I think said that multiple episodes of depression had a stronger genetic basis compared to those who had only one episode. I think it was a paper by Kenneth Kendler using some data on twins.

DD S: When discussing our question, one big reason for people wanting to know the answer is the hope that if there were ways to predict at first episode which people would have a one-off and which would be likely to have repeated episodes, then maybe those groups could be treated differently.

Do you know if GPs or psychiatrists ask people if they have family members who’ve experienced depression, when they are diagnosing them?

Matthew: There is certainly a READ code (one of the codes GPs use when entering a record) that is for family history of depression, but whether it’s used (due to time limits) or accurate, who knows. It would be possible to check accuracy by comparing to cohort questionnaire data, as Mark Adams suggested above

DD C: I’m beginning to wonder whether our research could be to do interviews with people who have a history (current or past) of depression and see whether their experiences are adequately assessed by the standard questionnaires!!! I’m not being completely flippant here, since I think the relative triviality of the questions reflects the lack of adequate treatment options….

Matthew: The problem with that approach is that clinicians and researchers really do need standardised questionnaires. They may not be the best, and they may not suit all cases, but they allow us to compare between studies/populations/countries.

DD N: I guess perhaps the question is then whether the standard questionnaires could be improved! I’d be interested to know how long ago the current ones were created

DD C: I know. I guess I’m just a bit cynical because I don’t feel it applies to me and because I have witnessed so much inappropriate use of them….

DD S: Also, in practical terms, that would probably need a new ethics application and we probably can’t do that in time.

DD C: Do you think it would be interesting to have feedback from our group on these questionnaires?

Matthew: I think that would be great: most of the questionnaires were designed by clinicians. I would say constructing a more patient-led questionnaire is fantastic, but would take a while – probably more time than you have here. Something to come back to, though!

DD C: I’d certainly be up for it if you ever wanted to attempt it!

DD C: Maybe we could pick out some questions , even if it’s not the full questionnaire…

DD N: I’m afraid that’s our hour and we’ll have to let the researchers go now – thanks so much for coming Alex, Mark and Matthew

Alex: Thanks for having us! Really interesting to talk to you and discuss these ideas!

DD S: No. Lock the doors. Stop them from leaving.

(OK, I’m joking.)

Thank you for coming Mark, Matthew and Alex, it’s been fantastic and so useful.

DD C: Thank you all so much! It’s been really enlightening

Matthew: Thanks everyone, it’s been great. It’s tough to nail down a research question – happy to come back to this and any other questions another time.