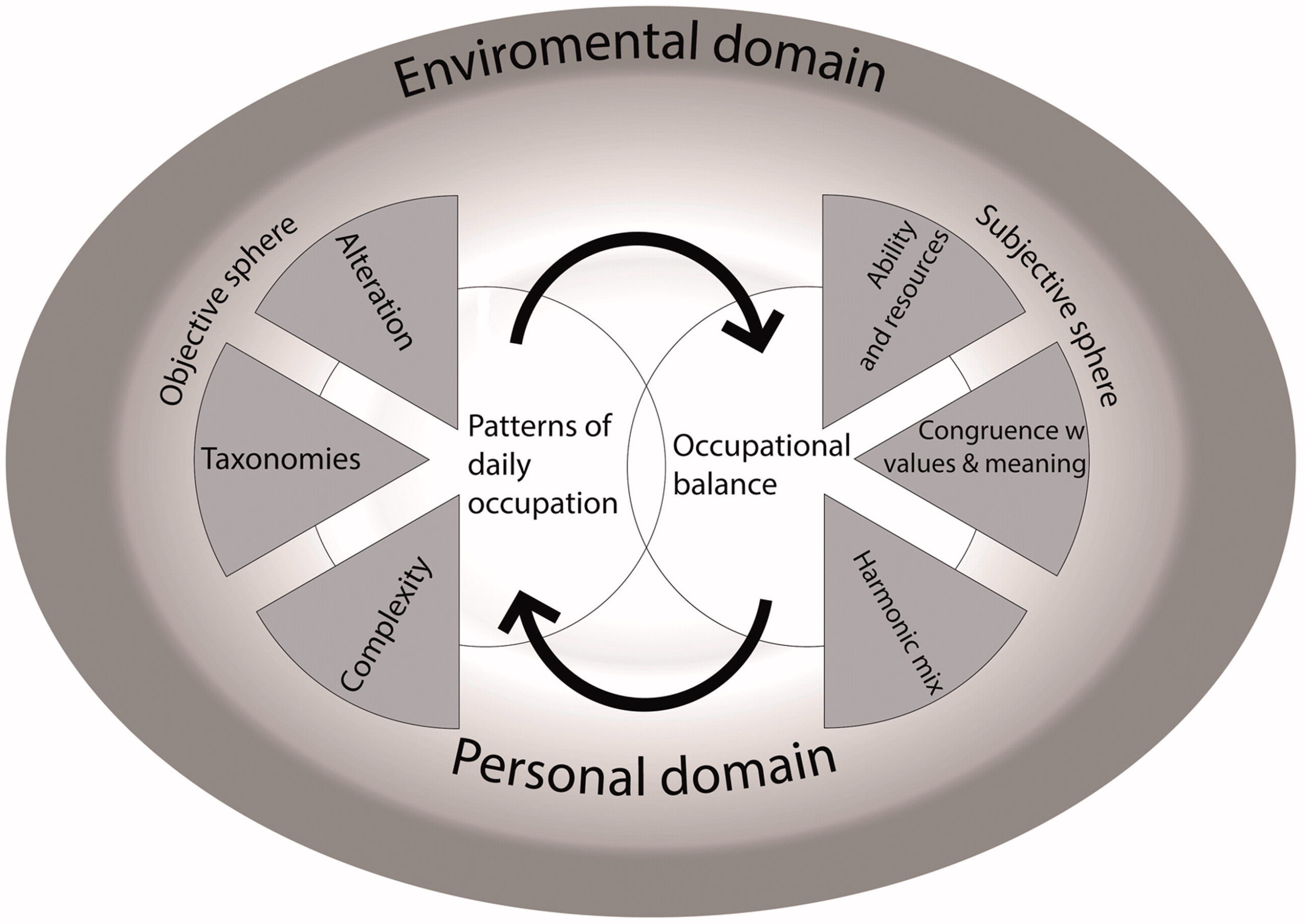

The previous two blogs↗️ set the scene by first unpacking occupation as a construct of ‘doing’ intrinsically linked to human health, then suggesting a pedagogical framework situating occupation in the context of Higher Education (HE). This blog takes a lens to specific occupations in HE, positioning them within Ekland et al’s (2017)↗️ model of occupational balance (Figure 1). Again, as my role is that of a teacher, largely teaching occupations are considered, but the occupations of learning equally merit examination.

As introduced in Blog 2, ‘taxonomies’ of occupation present a way to archetype and categorise the activities involved. A taxonomic approach was originally developed in professional occupational therapy to advance a common language and schema around core therapeutic occupations (Holmqvist and Holmefur, 2018)↗️. Although problematic due to the narrowness and ‘normativity’ of categorisation (Njelesani et al, 2015)↗️, none the less, a taxonomic approach is one way to unpack and examine the human actions and functions involved in the occupations of teaching and learning.

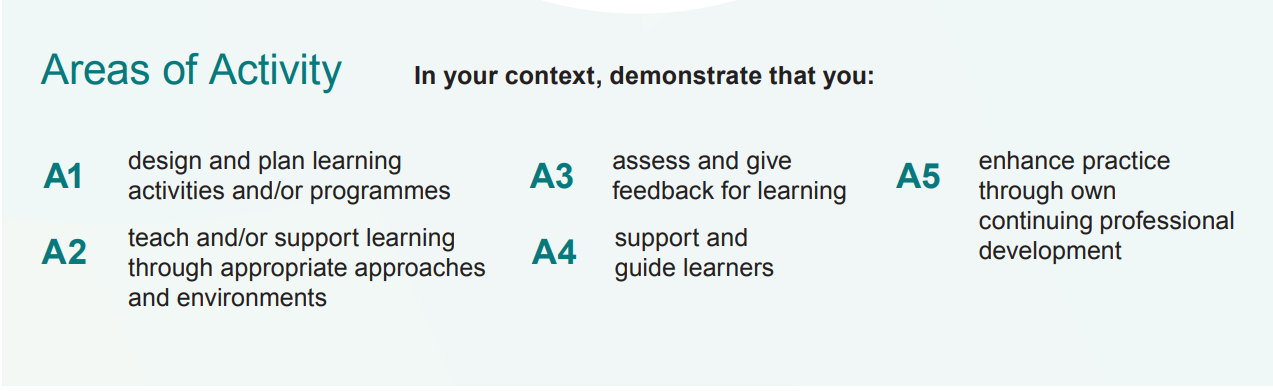

A taxonomy of occupations related to archetypes of activity in HE teaching and learning is yet to be developed. However, typologies of teaching and learning which set out the common structures (or ‘dimensions’) involved in different activities do exist. One such typological framework has been developed by Advance Higher Education (Advance HE), namely the ‘Professional Standards Framework↗️’, or ‘PSF’ (Advance HE, 2023↗️).

Aiming to be a global framework of dimensions related to teaching practice, through which teaching accreditation can be achieved, the PSF is not without limitations. Considered to be too narrow in “focus, content and requirements” (van der Sluis, 2023, p 425↗️) it offers limited scope to engage with practice dynamically and iteratively and does not do enough to bring to light much of the ‘invisible’ work of HE (see also Lawless, 2018↗️). That said, the PSF is a typological framework of ‘Activities, Knowledge, and Professional Values’ (Advance HE, 2023↗️) mapped to HE-teaching practice.

For the purposes of this blog, the five PSF ‘Areas of Activity’ (Advance HE, 2023↗️) (Figure 2) are of particular interest as a typology. As such, they provide a place to start to explore how teaching and learning activity might translate to not only occupations in HE and their situation more broadly (Figure 1), but also what might lead to occupational dysfunction (Hammell, 2015)↗️ with potential impacts to health.

Activities 1-4 in Figure 2 link more directly to the praxis of teaching. Activity 5, the activity of ‘’enhancing practice through own continuing professional development” (Advance HE, 2023, p 5)↗️ has most interest here. ‘A5: enhancing practice’ not only asserts the importance of continuing professional development, but through this process individuals could potentially become more established, experienced, and fulfilled as educators. Taking a contrasting view, failure to develop professionally as a teacher due to external or internal challenges has the potential for negative impacts.

Following this example, failure to progress could mean limited opportunity for promotion, lost employment opportunities and consequent impacts on personal finances. Linking this to health and wellbeing, a large body of evidence already links income inequality to poorer health (see for example Pickett and Wilkinson, 2015↗️). However, other health impacts from ‘failure to progress’ can occur; failure to meet personal and professional expectations has the potential to impact mood, self-image, and satisfaction. These facets of response have been termed feelings of ‘subjective wellbeing’ and multiple studies including those of Steptoe, Deaton, and Stone (2015)↗️ and Seligman (2018)↗️ have linked subjective wellbeing to health.

Linking back to Blog 2↗️, a (dis)hormonic mix between activities in A5, enhancing practice, and those of A1-4 could occur because of limited time, resources, or opportunity to take part in activities related to A5. For example, if most (personal) resource goes towards A2 (teaching and supporting learning), it follows there is limited opportunity to focus on personal development (A5). An occupational dysfunction occurs, occupations are out of balance, and the occupation of enhancing practice is marginalised.

Although theoretical, this example does translate to the current context of HE. Even before the significant disruption caused by the Covid 19 pandemic, Morrish (2019)↗️ highlighted poor mental wellbeing, especially feelings of stress and burnout, in HE professionals compared to the general population. Described as “the epidemic of poor mental health among higher education staff” (Morrish, 2019↗️, paper title), reasons for this have been attributed to increased workload, scrutiny around metrics and performance, and an increasingly competitive working culture (Jayman, Glazzard and Rose, 2022)↗️. Taken together, Ball and Olmedo (2013, p85)↗️ describe this as a situation where

“academics are busier and working faster than ever, while the focus is on what we do rather than on who we are” (my emphasis).

It is the ‘do’ in Ball and Olmedo’s observation that has resonance with a pedagogical framework for occupation. If academics are (over)doing work to fit current academic expectations, then occupational disharmony exists in everyday teaching occupations. This makes clearer a potential relationship between occupation, health, and HE. While work over-load at the personal level is a serious contemporary issue in HE, other threats to health are also emerging and they will be explored in the blogs that follow.

References

Advance HE (2023). Professional standards framework (PSF). https://advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/professional-standards-framework-teaching-and-supporting-learning-higher-education-0 [Accessed 19 November 2023].

Ball, S. J., and Olmedo, A. (2013). Care of the self, resistance, and subjectivity under neoliberal governmentalities.↗️ Crit. Stud. Educ. 54, 85–96. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2013.740678

Gray, J.M. (1998). Putting occupation into practice: Occupation as ends, occupation as means. The American journal of occupational therapy, 52(5), pp.354-364.

Hammell, K.W. (2015). Participation and occupation: The need for a human rights perspective↗️. Canadian journal of occupational therapy, 82(1), pp.4-5.

Holmqvist, K.L. and Holmefur, M. (2018). The ADL taxonomy for persons with mental disorders–Adaptation and evaluation↗️. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 26:7, 524-534

Jayman, M., Glazzard, J. and Rose, A. (2022). Tipping point: The staff wellbeing crisis in higher education↗️. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p. 929335). Frontiers.

Lawless, B. (2018). Documenting a labor of love: Emotional labor as academic↗️. Review of communication, 18(2), pp.85-97.

Morrish, L., 2019. Pressure vessels: The epidemic of poor mental health among higher education staff. Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute. https://healthyuniversities.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HEPI-Pressure-Vessels-Occasional-Paper-20.pdf↗️ [Accessed 22 November 2023].

Njelesani, J., Teachman, G., Durocher, E., Hamdani, Y. and Phelan, S.K., 2015. Thinking critically about client-centred practice and occupational possibilities across the life-span↗️. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 22(4), pp.252-259.

Pickett, K.E. and Wilkinson, R.G., 2015. Income inequality and health: a causal review↗️. Social science & medicine, 128, pp.316-326.

Seligman, M., 2018. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being↗️. The journal of positive psychology, 13(4), pp.333-335.

Steptoe, A., Deaton, A. and Stone, A.A., 2015. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing↗️. The Lancet, 385(9968), pp.640-648.

van der Sluis, H., 2023. ‘Frankly, as far as I can see, it has very little to do with teaching’. Exploring academics’ perceptions of the HEA Fellowships↗️. Professional development in education, 49(3), pp.416-428.

Kirstin Stuart James

Kirstin Stuart James

Dr Kirstin Stuart James is currently on secondment as Deputy Programme Director within the Clinical Sciences Teaching Organisation, part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine at University of Edinburgh. As her substantive post, Kirstin is Senior Academic Coordinator/MSc Year Lead in Clinical Education where she teaches on online distance learning programmes for those involved in undergraduate and postgraduate education across the health and veterinary professions. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. Kirstin is also a Senior Occupational Therapist in Urgent and Emergency Care with NHS Lothian. Kirstin is interested in the links between health and education, and how an understanding of occupation and occupational therapy can enrich teaching, learning and educational design, and support health though education. You can find Kirstin on Twitter (X) at @TherapyStatim↗️.